15 world attractions that used to be hated

From loathed to loved

Kirill Neiezhmakov/Shutterstock

The world's most well-known attractions and landmarks attract millions of visitors each year between them, but their popularity is something that has taken time. Whether due to design disagreements, politics or financing issues, some sites were initially resented by local residents, tourists and experts.

Read on as we reveal the world's most famous attractions that were hated when they were first built...

Eiffel Tower, Paris, France

Fine Art Images/Heritage Images via Getty Images

The Eiffel Tower in Paris is one of the world's most famous attractions, but it was subject to much criticism in its early years. Gustave Eiffel, having beaten fierce competition to build a tower for the 1889 World Exhibition, then faced attacks from critics who declared it "useless and monstrous". The world's then-tallest tower faced demolition 20 years after opening, but Eiffel saved it by promoting all its scientific benefits, such as using it as a transmitter for wireless telegraphy.

Eiffel Tower, Paris, France

Vibe Images/Shutterstock

Standing at 1,083 feet (330m), the Eiffel Tower is no longer the world's tallest – that honour is now held by Dubai's Burj Khalifa, which is almost three times taller – but remains a much-loved symbol of Paris and France itself. Visitor numbers hit 6.32 million in 2023 and it has spawned copies worldwide including in Las Vegas, home to the world's tallest direct replica; Tokyo, whose own Eiffel-inspired tower is 30 feet (9m) taller than Paris; and in the UK seaside resort of Blackpool.

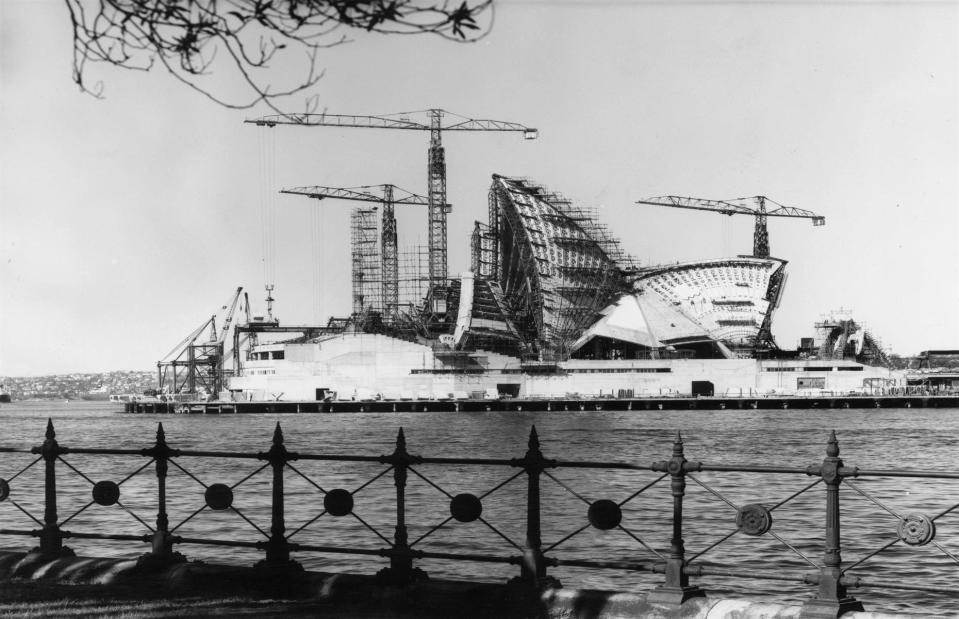

Sydney Opera House, Sydney, Australia

J. R. T. Richardson/Fox Photos/Getty Images

The Sydney Opera House is one of the world's most famous buildings, so it may come as a surprise to many that its designer, architect Jorn Utzon, had relatively little experience. Construction on the Dane's nature-inspired design began in 1959 but the project was beset by challenges including cost overruns and structural difficulties – such as how to get the enormous white shells to 'float' in the air. Such issues and ongoing disagreements with the government led to Utzon's resignation in 1966.

Sydney Opera House, Sydney, Australia

Richie Chan/Shutterstock

A new panel of Australian architects was chosen to run the beleaguered project. Sydney Opera House was finally opened by Queen Elizabeth II on 20 October 1973 – 10 years late and having cost 14 times more than originally planned – and Utzon was not mentioned in any of the speeches. Decades later, he was invited back to oversee its restoration and finally got to see his masterpiece. The building was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2007 and welcomes 10.9 million people a year.

Mount Rushmore, South Dakota, USA

George Rinhart/Corbis via Getty Images

The idea of a colossal monument in the Black Hills of South Dakota was first mooted by state historian Doane Robinson in 1923 to honour the West's heroes, both Native Americans and pioneers. But sculptor Gutzon Borglum thought four presidents would better reflect US history: George Washington as the country's founder; Thomas Jefferson to represent its expansion; Theodore Roosevelt to highlight its development as a global power; and Abraham Lincoln for its preservation after the US Civil War.

Mount Rushmore, South Dakota, US

Klaus Steinkamp/Shutterstock

Work began on the monumental project in 1927 and was marred by funding shortfalls, design issues and the death of Borglum just months before its unveiling in 1941. However, many Native Americans saw – and continue to see – the site as symbolic of the poor treatment of the Indigenous people and appropriation of their land, leading to months-long protests in 1970. Today, Mount Rushmore attracts over two million visitors a year, although debate about how to best honour its original inhabitants remains.

Most SNP, Bratislava, Slovakia

SilvanBachmann/Shutterstock

Completed in 1972, Bratislava's Most SNP – meaning the 'Bridge of the Slovak National Uprising' – was built in honour of the 1944 resistance movement against the Nazis. However, this modernist masterpiece almost immediately became known as the 'UFO Bridge' due to its distinctive observation deck. Its construction also caused much controversy as many of the Slovakian capital's period buildings and an old synagogue were destroyed to make way for the bridge and accompanying highway.

Most SNP, Bratislava, Slovakia

Wandering News/Shutterstock

Many locals also called it 'New Bridge' and in 1993, city councillors voted to change its name to reflect this. However, several more bridges have been built since, rendering the 'new' somewhat redundant, so on 29 August 2012 the name was changed back on the 68th anniversary of the uprising. Today, its flying saucer appearance is embraced in the name of the UFO.watch.taste.groove restaurant and visitors can take a lift to the 312-foot-high (95m) observation deck for views over the city.

Burj Khalifa, Dubai, UAE

Chris Jackson/Getty Images

Standing 2,717 feet (828m) tall, Dubai's Burj Khalifa is currently the world's tallest building. When it opened in 2010 after six years of construction and controversies, including worker protests and pay disputes, its audaciousness was seen by some as a symbol of the decade's over-consumption, with one newspaper describing it as a "bleak symbol of Dubai's era of bling". It was also criticised for having 29% of 'vanity height', referring to the difference between its pinnacle and its highest usable floor.

Burj Khalifa, Dubai, UAE

Kirill Neiezhmakov/Shutterstock

Originally called the 'Dubai Tower', there were some raised eyebrows when the name was abruptly changed upon opening to 'Burj Khalifa', named after the then-president of the UAE and Abu Dhabi ruler, Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed al-Nahyan, just a month after Abu Dhabi gave Dubai a $10 billion bailout. While some remain yet to be convinced by the structure, its ostentatiousness certainly doesn't put off the 17 million visitors a year whose ears pop on the way up to Level 125's observation deck.

Tower Bridge, London, England

Detroit Publishing/Buyenlarge/Getty Images

Tower Bridge is one of London's most-loved landmarks but it wasn't always as popular. Originally designed by Sir Horace Jones and adapted into a more Gothic style by George D. Stevenson after his death, Tower Bridge features a drawbridge to enable ships to pass and high-level walkways so pedestrians could cross even when the bridge was open. However, these walkways soon became a haunt for pickpockets and prostitutes and they were closed to the public in 1910, only reopening in 1982.

Tower Bridge, London, England

Sven Hansche/Shutterstock

Early observations of Tower Bridge weren't particularly endearing either. In 1916, architect H.H. Statham wrote that it represented "the vice of tawdriness and pretentiousness", while the Pall Mall Gazette complained of the "variegated ugliness" of its Gothic style. However, Londoners have grown to love it over time, with the bridge featuring heavily in the pomp and ceremony around the London 2012 Olympics. Some 114,000 people visited last summer alone, with many more admiring it from the embankment.

Palace of the Parliament, Bucharest

Peter Turnley/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images

Bucharest's Palace of the Parliament is the second largest administrative building in the world after the US Pentagon. Started in 1984, the colossal 3.9 million square foot building (365,000sqm) was the brainchild of former dictator Nicolae Ceausescu, who seized upon the devastation caused by the 1977 earthquake to bulldoze much of old Bucharest. The oversized and overly-ornate palace was supposed to symbolise the success of communism in Romania and be an emblematic residence of the Ceausescu family.

Palace of the Parliament, Bucharest

Balate.Dorin/Shutterstock

After the violent fall of Ceausescu in 1989, Romanians didn't know what to do with the symbol of oppression under communism. However, it was cheaper to continue than demolish it and construction resumed between 1992 and 1996. What was initially called the People's House was renamed the Palace of the Parliament and now hosts the Romanian parliament, museums and a conference centre. There are paid tours of the building, which probably helps cover the £159,000 ($202,375) a month it generates in energy bills.

Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, Spain

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Barcelona's ever-unfinished Sagrada Familia will hit a major milestone in 2026 when the completion of the 564-foot (172m) Tower of Jesus makes it the world's tallest church. Construction began in 1882, but was stopped in 1926 after architect Antoni Gaudi's untimely death in a tram accident. Various architects then had to decipher his complex designs to continue the organic form cathedral, but work was halted in the 1930s due to a fire during the Spanish Civil War and it has repeatedly faced financing issues.

Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, Spain

Vunav/Shutterstock

The completion of the Sagrada Familia is now being funded by entry tickets and anonymous donations, but the final plans remain controversial with locals as a faithful reconstruction of Gaudi's doorway would see the demolition of two neighbouring blocks of businesses and 150 homes. Nevertheless, the cathedral remains the jewel in Barcelona's crown and more than 3.7 million visitors flocked here in 2023 alone to admire its unique and quirky design, described by some as looking like a 'castle of coral'.

Centre Pompidou, Paris, France

AFP via Getty Images

The 'inside out' machine age masterpiece that is the Centre Pompidou certainly ruffled a few feathers when it opened in 1977. Although it was the brainchild of former French prime minister Georges Pompidou, who saw a multimedia arts centre as a way of rejuvenating the Beaubourg area of Paris, the design by Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers was inspired by a new generation of museums in the US, such as the Guggenheim. Nowadays such centres are commonplace in many cities, but to some Parisians its machine-like appearance was a scandal.

Centre Pompidou, Paris, France

Pascale Gueret

Upon its opening, local newspaper Le Figaro declared: "Paris has its own monster, just like Loch Ness." However, the public were enthralled by the external escalators and lifts with great views, which also free up extra exhibition space inside. Slowly but surely, Parisians took the Centre Pompidou into their hearts, along with the three million people who come here each year to view Europe's largest collection of modern and contemporary art. It will be shut for renovations for five years from 2025.

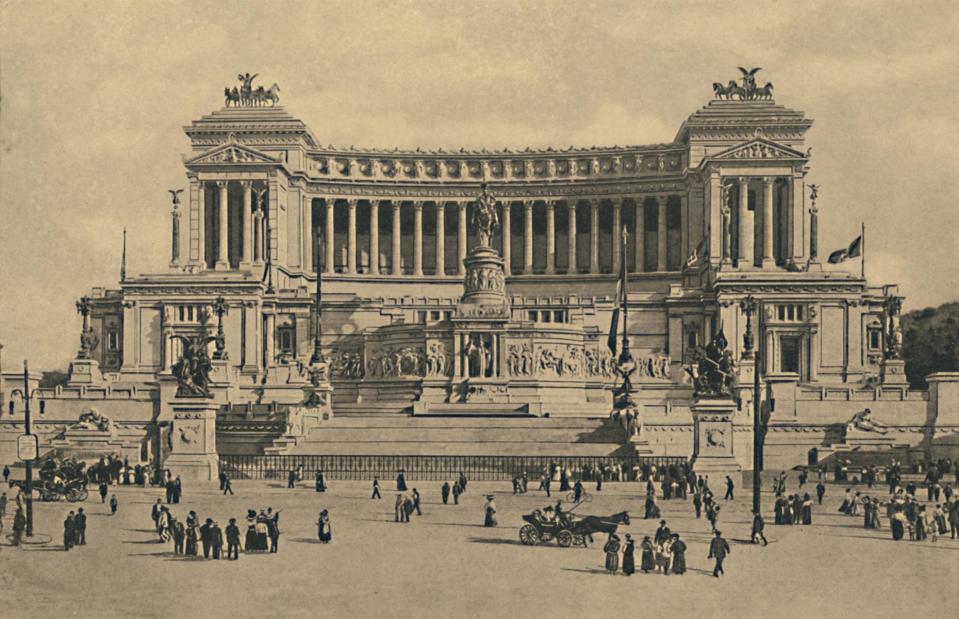

Victor Emmanuel II Monument, Rome, Italy

Print Collector/Getty Images

Victor Emmanuel II Monument at the foot of Capitoline Hill in Rome celebrates the unification of Italy and honours Victor Emmanuel II, the first king of a fully-reunified Italy. Designed by Giuseppe Sacconi in 1885 and inaugurated in 1911, the large Neoclassical structure is sometimes referred to as looking like a wedding cake or a typewriter (the latter a moniker given to it by the Americans in 1944). A medieval neighbourhood and part of Capitoline Hill were also destroyed to make way for it.

Victor Emmanuel II Monument, Rome, Italy

Viacheslav Lopatin/Shutterstock

Others criticise the gleaming white appearance of the marble monument for being somewhat incongruous with the more earthy hues of the surrounding buildings. Nevertheless, the building – commonly known as Il Vittoriano – remains a symbol of Italian unity and identity and an eternal flame burns here at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. Love it or loathe it, you certainly can't ignore it, and visitors flock here to take the elevator to the roof for spectacular views over the Italian capital.

Guggenheim Museum, New York, USA

Charles Phelps Cushing/ClassicStock/Getty Images

New York City's Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum certainly broke with tradition when it came to architectural rules. The curves of Frank Lloyd Wright's 1959 masterpiece stood in stark contrast to the linear architecture around it, prompting negative comparisons with marshmallows, washing machines and a corkscrew. The New York Times complained that the spiral design that guides people through the building and its art exhibits acted as a "kind of strait jacket for the visitor".

Guggenheim Museum, New York, USA

f11photo/Shutterstock

Today the Guggenheim, as it's more commonly known, is recognised as one of the 20th century's most significant architectural icons. Housing one of the world's foremost contemporary art collections, the building was declared a US National Historic Landmark in 2008 and added to UNESCO's World Heritage List in 2019. Other branches of the world-famous museum exist in Bilbao, Spain and Venice, Italy; with another scheduled to open in Abu Dhabi in 2025.

Dancing House, Prague, Czechia

AA World Travel Library/Alamy Stock Photo

The Dancing House on the banks of the Vltava in the Czech capital of Prague was based on an idea by Vaclav Havel, the president of Czechoslovakia (now Czechia) after the Velvet Revolution. The house, nicknamed 'Fred and Ginger' after Hollywood dance stars Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, is built on what was a Second World War bomb site, situated next door to Havel's apartment block. After the overthrow of communism in 1989, Havel re-examined the idea with his friend, the renowned architect Vlado Milunic.

Dancing House, Prague, Czechia

Jaroslav Moravcik/Shutterstock

US architect Frank Gehry, who had a similarly non-traditional approach to architecture, was also brought on board to design the project and the deconstructivist Dancing House finally opened in 1996, a symbol of Czechoslovakia's transition to becoming a modern democracy. Many locals weren't keen on how much it jarred with the Baroque, Gothic and Art Nouveau buildings surrounding it, but it has since achieved cult status and even featured on a commemorative coin issued by the Czech National Bank.

Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral, Liverpool, England

PA Images / Alamy Stock Photo

In the early 1930s, Liverpool's Catholic Archbishop Richard Downey and architect Sir Edwin Lutyens launched ambitious plans to build one of the world's largest cathedrals with a dome like St Peter's Basilica in the Vatican – partly in response to the nearby rival Anglican cathedral that was increasingly looming over the English port city. But while ground was broken in 1933, work was brought to a stop by the Second World War and post-war costs spiralled out of control, leading to a design rethink.

Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral, Liverpool, England

Alexey Fedorenko/Shutterstock

The substitute was the Sir Frederick Gibberd-designed Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King, to give it its full title, that was consecrated in 1967 having been built in under eight years. The concrete modernist masterpiece was praised by architects but others were less keen – with many referring to its appearance as looking like a blown-up tent or spaceship. However, it is now very much a symbol of Liverpool and part of the landscape, standing in stark contrast to its neo-Gothic neighbour, Liverpool Cathedral.

Berliner Fernsehturm, Berlin, Germany

Sueddeutsche Zeitung Photo / Alamy Stock Photo

Standing at 1,207 feet tall (368m), Berlin's Fernsehturm, or TV tower, is the tallest structure in Germany – and one of the tallest in Europe. It was designed by socialist authorities in the 1960s as a broadcasting tower that also showed off the strength and prowess of East Germany as it could be seen across the divided city. Indeed, its sphere was supposed to remind people of Soviet sputnik satellites and was to be lit up in red, the colour of socialism.

Berliner Fernsehturm, Berlin, Germany

canadastock/Shutterstock

By the time the Fernsehturm opened in 1969, the East German tower was not without controversy, notably because it was also used for surveillance. One seemingly unanticipated detail was that the sun shining on the stainless steel sphere creates the image of a cross – something that was a bit embarrassing for the secular authorities, leading to its nickname the 'Pope's Revenge'. Nowadays, it's a symbol of reunification and how Berlin has dealt with its complex history.

Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Washington DC, USA

Diana Walker/Getty Images

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington DC honours the 58,318 men and women who were killed or missing in action while serving for US armed forces during the Vietnam War of 1955-75. The memorial was designed by US architect Maya Lin and is a black granite V-shaped wall inscribed with the victims' names and sloping down into the ground in the middle. However, its minimalist appearance initially proved controversial as it lacked the heroic design or sculptures of more traditional memorials.

Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Washington DC, USA

Baiterek Media/Shutterstock

A compromise was eventually reached when a flag and a more traditional statue of three servicemen were added at the entrance before the Vietnam Veterans Memorial was dedicated on 13 November 1982. Having once been criticised for being a "black gash of shame" or like a scar, the monument remains a popular and moving attraction, with five million people coming here each year. The Vietnam Women's Memorial and the In Memory plaque were added in later years.

Now discover the awesome American attractions that never got built