14 tourist attractions that epically flopped

Fatal attractions

ZUMA Press Inc/Alamy Stock Photo

If you build it, there is a chance they might not come. At least, that’s what happened with many of these attractions that failed to take off. Some enjoyed initial success but were finally derailed by scandal, financial problems or poor management. Others were always unpopular.

From white elephants like North Korea’s so-called ‘Hotel of Doom’ to recent embarrassments like London’s Marble Arch Mound, here are some of the world’s epic tourist attraction fails.

Spreepark, Berlin, Germany

RobertKuehne/Shutterstock

Headless dinosaurs, a frozen Ferris wheel and rides reclaimed by nature and covered in graffiti: the remains of Berlin’s Spreepark have themselves become something of a tourist attraction. It originally opened in 1969 as the VEB Kulturpark Plänterwald and was East Germany’s only amusement park, attracting 1.7 million visitors each year. It somehow survived following the fall of the Berlin Wall and was renamed in 1991, with new operator Norbert Witte adding rides from the defunct Mirapolis park near Paris.

Spreepark, Berlin, Germany

Mo Photography Berlin/Shutterstock

At one point he even added an English-style village. But it emerged he was smuggling cocaine in pieces of ride equipment shipped across from Peru. That scandal, and dwindling visitor numbers, led to the park closing in 2002 (Witte was convicted in 2004). The abandoned park was partly destroyed by a deliberate fire in 2014 and the site was taken over by a city-owned company two years later. It’s being transformed into an urban park with tours around the old structures and plans to get the Ferris wheel turning again by 2024.

Revel Casino, Atlantic City, New Jersey, USA

B64/Wikimedia Commons/CC-BY-SA-3.0

New Jersey's Revel Casino was declared all-out less than three years after opening, with the £1.8 billion ($2.4bn) project mired in financial difficulties. The beachfront building – the tallest in Atlantic City and one of the country’s tallest casinos – suffered setbacks and tragedy from the start, with three executives of Revel Entertainment and its construction company killed in a 2008 plane crash. The financial crisis caused more issues and investors Morgan Stanley pulled out of the project in 2010.

Revel Casino, Atlantic City, New Jersey, USA

Farragutful/Wikimedia Commons/CC-BY-SA-4.0

Revel managed to secure financing and opened in 2012 with two 700-foot (213m) towers and more than 1,800 hotel rooms, although the original plans were for 4,000. However, it failed to recoup its losses. This photo was taken in 2014, the year Revel closed. It’s now been reopened as Ocean Resort Casino, although there have been reports of financial struggles.

Alps Ski Resort, Heul-ri, South Korea

ED JONES/AFP via Getty Images

The Alps Ski Resort wasn’t a complete failure. In fact, it was a huge success for decades. It opened in the 1980s in Heul-ri, a tiny settlement close to the Demilitarised Zone that divides South from North Korea. The once vibrant resort, one of the country’s first winter sports destinations, drew tens of thousands of visitors each year. Its high-altitude position meant it enjoyed the heaviest natural snowfall in the country, with skiers coming here even before the resort opened.

Alps Ski Resort, Heul-ri, South Korea

ED JONES/AFP via Getty Images

The Alps closed in 2006, faced with competition from resorts with sleeker facilities. Plans to rescue and renovate it have so far failed to come to fruition. Rusting and empty structures include swimming pools, hotels, restaurants and shops filled with heaps of skis and snow boots. This photo shows a ski lift in the abandoned resort, where local business owners and other villagers say they have been left struggling.

South China Mall, Dongguan, China

Johan Nylander/Alamy Stock Photo

South China Mall was the world’s largest when it opened in 2005, with more than five million square feet (465,000sqm) of retail space and room for up to 2,350 stores. It’s more than twice the size of the USA’s biggest shopping centre, Mall of America. Yet only a handful of spaces – around 1% – were occupied and the mall failed to attract anything close to the hoped-for 100,000 visitors per day. Observers suggested the remote location outside the centre of Dongguan was partly to blame.

South China Mall, Dongguan, China

Johan Nylander/Alamy Stock Photo

There have been several attempts to reverse the mall’s fortunes, including the addition of an outdoor amusement park with a giant Egyptian sphinx, a replica of Paris’ Arc de Triomphe and a mini Venice with canals and gondolas – this photo shows the area’s construction in 2015. It was hoped more extensive renovations, including an IMAX-style cinema, might bring more visitors in, but it’s still far from the bustling shopping centre once envisioned.

World Islands, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Markus Mainka/Shutterstock

Dubai tends to do everything on a bigger, bolder scale and its less-than-successful attractions are no exception. In this case, the entire world failed to take off. The World Islands was supposed to be a man-made archipelago designed to resemble a map of the world, with the 300 landmasses grouped into continents. Potential purchasers were believed to include Richard Branson, Karl Lagerfeld – who planned a fashion-themed island – and Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie.

World Islands, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Mike Fuchslocher/Shutterstock

With the developer Nakheel, who created the Palm Jumeirah, behind the project, it seemed bound to succeed. Except, of course, it didn’t. Construction began in 2003 but was put on hold due to the 2008 financial crisis. There were even reports that some of the private islands, which had been priced at £11-37 million ($15-50m) each, were starting to sink. Today, only a few have been developed, although some projects – including the Heart of Europe resort – are being resumed.

Shania Twain Centre, Timmins, Ontario, Canada

What A Ride/Flickr/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

On paper, a museum dedicated to the world’s all-time best-selling female country music artist should have been a rip-roaring success. In reality, the Shania Twain Centre barely entered the charts. The centre opened in 2001 in Timmins, where the singer grew up and started her career. Its relatively remote location, though, proved part of the problem and it drew fewer than 15,000 visitors in 2002.

Shania Twain Centre, Timmins, Ontario, Canada

Bill Platten/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 2.0

The museum’s focus didn’t impress people much either: exhibits of memorabilia related to Twain’s career featured alongside completely unrelated gold-mining artefacts. Numbers only tumbled and the city-funded centre was operating at a loss. It could still prove to be a goldmine, though. When the centre eventually closed in 2013 the land was sold to Goldcorp with plans to demolish the building and replace it with an open-pit mine. The singer still has a street in Timmins named after her (pictured).

Wonderland Amusement Park, Beijing, China

Bertrouf/Wikimedia Commons/CC-BY-SA-3.0

Not every fairy tale has a happy ending, and particularly not the story of Wonderland Amusement Park just outside Beijing. It was supposed to be China’s answer to Disneyland and the biggest theme park in Asia at 120 acres, making use of barren land outside the capital. Construction began in the mid-1990s but was abandoned in 1998 amid disputes over money and land.

Wonderland Amusement Park, Beijing, China

Imaginechina Limited/Alamy Stock Photo

The pastel turrets of its Cinderella-style castle stood for years as an eerie reminder of the failed project, surrounded by smaller structures and half-finished areas. Apparently workers could often be seen tilling the area’s cornfields. The park was eventually demolished – along with the fairy tale – in 2013, as shown in this picture. Adding insult to injury, Shanghai Disneyland Park opened in 2016.

Son of Beast, Kings Island, Mason, Ohio, USA

Jeremy Thompson/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

There have been a few short-lived roller coasters over the years but Son of Beast is perhaps the one surrounded by the biggest initial hype. Kings Island opened in 1972 and became famous for The Beast, the world’s longest wooden roller coaster at 7,359 feet (2,243m). The thrilling coaster covered a large span of the park and offered riders a privileged (if blurry) view over the surrounding landscapes. It was so popular that it birthed Son of Beast, the world’s tallest and fastest wooden roller coaster, in 2000.

Son of Beast, Kings Island, Mason, Ohio, USA

WillMcC/Wikimedia Commons/CC-BY-SA-3.0

The coaster loomed at about 218 feet (66m) and had a drop of 214 feet (65m), with riders whizzed around at just over 78 miles per hour (126km/h). Unfortunately it proved to be something of a problem child. In July 2006 the ride stopped abruptly towards the end due to a structural failure, injuring 27 people. Changes were made but, three years later, a woman claimed to have suffered a burst blood vessel in her brain after riding Son of Beast – and the ride was closed permanently, with pieces sold off.

Heritage USA, Fort Mill, South Carolina, USA

Bettmann/Getty Images

Heritage USA was opened in 1978 by televangelists Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker (pictured here at the park) and was marketed as a ‘Christian version of Disneyland’. The couple built a multimillion-dollar empire on the back of their TV network, The PTL (‘Praise the Lord’) Club, which asked viewers to pledge monthly to become ‘partners’. They used some of the money to buy 2,300 acres of land in the small town of Fort Mill, encouraging followers to pledge for lifetime memberships at the 500-room hotel and waterpark complex.

Heritage USA, Fort Mill, South Carolina, USA

SSE Photography/Shutterstock

Its fairy-tale castle and evangelism school drew millions each year. But then the scandals rolled in, most notably a string of allegations against Jim Bakker. He was jailed for 1989 for mail fraud, wire fraud and conspiracy to defraud the public. The same year, the park was hit by a hurricane – and never reopened. TThere was renewed interest in the torrid tale recently thanks to the 2022 movie The Eyes of Tammy Faye, with Jessica Chastain in the title role and Andrew Garfield as Jim. Pictured is Heritage Tower, built as the hotel, in 2019.

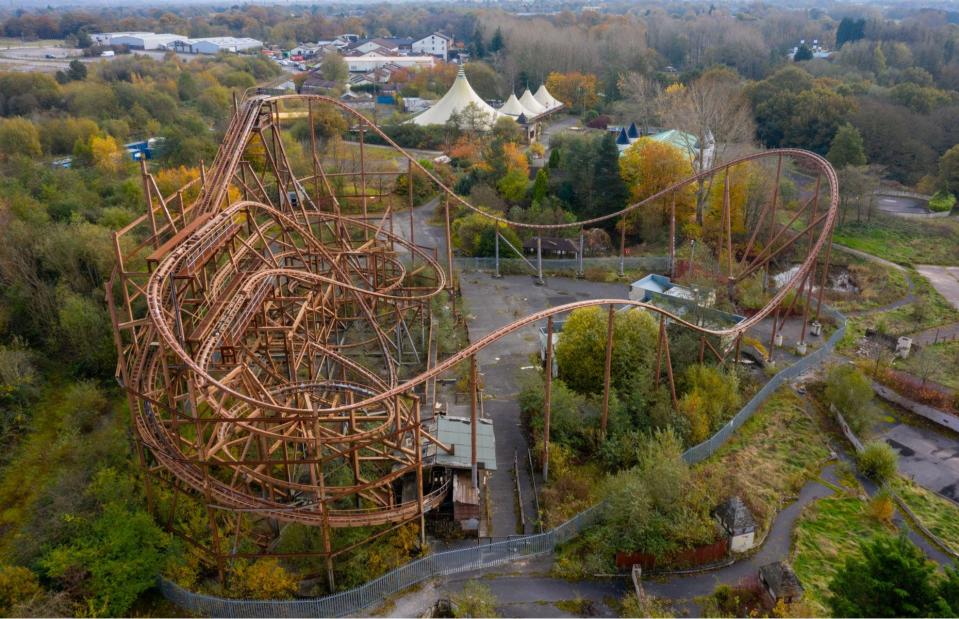

Camelot Theme Park, Charnock Richard, Lancashire, England, UK

JKinson/Wikimedia Commons/CC-Zero

There wasn’t one particular reason that Camelot Theme Park, which opened with much fanfare in 1983, eventually failed – rather, the 2012 closure was blamed on poor weather and being overshadowed by huge events including the London Olympics and Diamond Jubilee. The medieval-themed park was based on the legend of Camelot, King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, and featured roller coasters, gentler children’s rides, jousting events and Merlin’s castle (pictured in 2010).

Camelot Theme Park, Charnock Richard, Lancashire, England, UK

Christopher Chambers/Shutterstock

The park’s structures were finally dismantled in early 2020 and, later that same year, it was reported that chunks of the Knightmare roller coaster (pictured) were being sold on eBay. A new zombie attraction on the site, Camelot Rises, was launched in February 2022 (after its first scheduled event was cancelled due to a power outage), but appears to have fallen off the radar since.

Ozark Medieval Fortress, Lead Hill, Arkansas, USA

MRHSfan/Flickr/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

It was an interesting, if rather random, idea. A team of artisan builders, led by amateur archaeologist Michel Guylot, planned to build a replica of a 13th-century French castle equipped only with materials and tools available in medieval times, including a treadwheel crane powered by someone walking inside the wheel and used to hoist rocks. Rather than the project being completed before welcoming in tourists, it opened to the public in 2010 with visitors invited to watch the build develop over two decades.

Ozark Medieval Fortress, Lead Hill, Arkansas, USA

Grand Central USA!/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

By 2030, they predicted, the castle would be complete with 70-foot (21m) towers, a drawbridge and thick walls encircling a courtyard. Instead, it closed indefinitely in early 2012, with the owners blaming financial problems. Guyot had successfully launched a similar project, Guedelon, near Saint-Fargeau, France but, while that attraction drew 310,000 visitors in 2011, the Ozark Medieval Fortress brought in fewer than 12,000 in its first year. The barely-started structures remain in the woods, incongruous against the backdrop of the Ozark Mountains.

Millennium Dome, London, England, UK

John van Hasselt/Sygma via Getty Images

It certainly opened with a bang. Several bangs, in fact. The Millennium Dome – built to house a national exhibition – in London’s Greenwich was unveiled amid the firework displays of New Year’s Eve 1999 with around 10,000 guests including the Queen and then Prime Minister Tony Blair. The launch night itself was something of a disaster, with tickets failing to turn up on time and even a bomb threat (which turned out to be a hoax).

Millennium Dome, London, England, UK

Historic England/Heritage Images via Getty Images

Visitor numbers failed to meet the £789 million ($1bn) cost or cover ongoing expenses, and the dome was soon closed to the public. The structure was sold in December 2001 and for years loomed, as something of a white elephant, over the Thames. It was reopened in 2007 as The O2, finally enjoying some success as a concert and sporting event arena that regularly attracts big-name acts and tens of thousands of fans.

Marble Arch Mound, London, England, UK

Travers Lewis/Shutterstock

This sculpture of turf-covered scaffolding was supposed to be a model of urban greenery and boost business in London’s West End shops after the COVID-19 lockdowns. Instead it amounted to little more than a hill of beans. The Marble Arch Mound cost £6 million ($8.1m), way over the £3.3 million ($4.4m) budget, to construct and launch, with the idea that people could explore a verdant area with views over Oxford Street and Hyde Park. Yet it failed to attract enough visitors or live up to its promise.

Marble Arch Mound, London, England, UK

ZUMA Press Inc/Alamy Stock Photo

There was originally an entrance fee of up to £8 ($11) to clamber up the hill but even scrapping this – making the ‘attraction’ completely free – didn’t prevent complaints about the poor state of the mound, which reportedly offered dying plants and weedy trees instead of the promised lush vegetation. Its deconstruction was announced in February 2022.

Ryugyong Hotel, Pyongyang, North Korea

Chintung Lee/Shutterstock

Who fancies a stay at the ‘Hotel of Doom’? Even if you do, it isn’t really an option. The Ryugyong Hotel, as it’s officially named, was originally due to open in 1989. Although ground was broken on schedule in 1987, it’s been something of a monumental disaster. Construction of the pyramid-shaped skyscraper was slow, to say the least, due to budget issues. It did reach its planned height of 1,083 feet (330m) by 1992, making it Pyongyang’s tallest building (shown in the centre of this skyline photo).

Ryugyong Hotel, Pyongyang, North Korea

Truba7113/Shutterstock

Construction stopped completely in 1992, with the collapse of the Soviet Union hitting the state’s economy. The hotel loomed over the city, unclad, windowless and hollow, until a deal was struck with an Egyptian conglomerate and it was finally clothed in glass and steel by 2011. A planned 2013 opening under German hotel chain Kempinski failed to materialise and it remains a towering failure – with the dubious honour of being the tallest abandoned hotel in the world.