Young people are sick of working hard for no money – and are using social media to vent

Pizza Fridays. Bring-your-dog-to-work days. Away days in an escape room. All are well-known ploys the managerial class use to massage a docile workforce despite real-term pay cuts. And yet, we still bite. In fact, you might be reading this after working overtime for the umpteenth day this month, believing – hoping – it warrants more than limited career growth and a Christmas party budget that covers only the first round. Bad news, it might not.

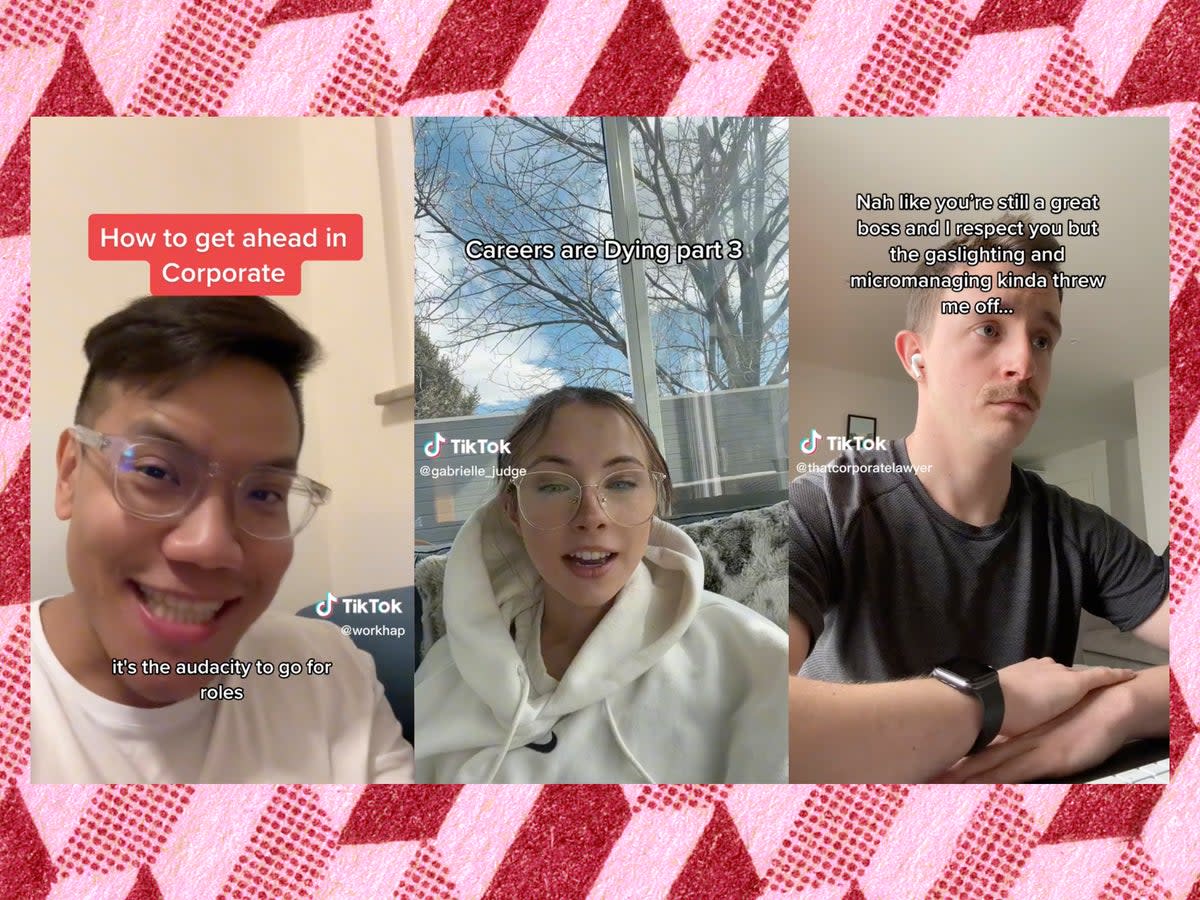

But don’t fret, for no one is fooling today’s young nine-to-fivers, who now find their balm to a bad day at the office or a marathon of aimless Zoom calls in the world of Corporate TikTok. Here, content creators rant, rave and spill the beans on toxic employer habits, offering you hacks and tips for everything from workplace red flags to the real meaning of a performance improvement plan (spoiler: you’re getting sacked). Some creators even go as far as filming their resignation process in videos known as “Quit-Toks”.

Rising from the ashes of a pandemic and the advent of hybrid working, young professionals are rejecting the old guard’s workplace ideology, conscious of the inflation and cost of living crisis looming above our heads regardless. Tackling phenomena like the Great Resignation, “quiet quitting” and “over-employment”, TikTokers are using these buzzwords as cannon fodder, critiquing the faceless monoliths of modern work. Forget collegiate camaraderie; now, the white-collar and Patagonia-gileted worker wants their job to feel valuable for them. Naturally, TikTok, a platform that embraces low-fi, serendipitous videos where users wear their hearts on their sleeves, has become the hub to rock the boss’s boat.

“Gone are the days of being ‘perfect’ on social media,” says Sho Dewan, the career coach behind the @workhap TikTok. “People want to see authenticity; they want creators to keep it real.” Indeed, this former recruiter and HR professional uses his past experience to share quick, consumable corporate cheat codes, helping prospective applicants fill vacancies and employees avoid scrapes with their employers. Titling his clips with clickbait like “Never share this to HR” and “The truth about salary negotiations”, Dewan provides truly insightful advice that many would be afraid to voice.

But this is just the tip of the iceberg. Elsewhere, many content creators cater their advice to specific demographics. Stephen Adeoye, a former corporate employee, runs the @corporatesteve TikTok as well as a recruitment agency, Beyond Education, focused on underrepresented talent in the finance and technology sectors. His account uses comedic dubs spliced with earnest commentary, pointing Black candidates to opportunities, one example being an “equality internship”. However, his approach is twofold, criticising the practice of diversity hiring as a back-handed compliment. In one clip, he opens it with the statement, “Guys, being a ‘diversity hire’ ain’t it”, before correcting himself: “Sike, it’s lit.” His position is undeniably a confusing one. His entrenchment in corporate philosophy also betrays itself in one particular clip, in which he uses a McKinsey study to back up the importance of having racially diverse teams to increase EBIT, or earnings before interest and tax.

So, what is the overarching objective? “There is a lack of transparency regarding what occurs in popular corporate industries and how to break into them,” he explains. “Ultimately, TikTok offers a space for people to gain valuable insights and experiences of the corporate world.” It’s laudable, as are his vocal thoughts on internal corporate problems – attending Thursday drinks to get promoted, for example – but overall, his is a less critical view. Indeed, studies on the benefits of a four-day working week don’t convince Adeoye, and while he’s aware of systemic racism in workplaces, he advocates against “playing the victim”.

As young people encounter more needless systematic bureaucracy, they will continue to instinctively share and call out stupid corporate behaviour

Connor Blakley, CEO of YouthLogic

Conversely, some TikTokers want to upend the system wholly, rejecting the Protestant ethic of working hard regardless of the yield – let alone institutional discrimination. In one clip that went viral, Gabrielle Judge (@gabrielle_judge), the self-proclaimed “Anti Work Girlboss”, shares a screenshotted forum thread in which one user shares his experience of being caught using a “mouse jiggler” – this is software that makes it appear as if remote workers are still active and online, all the while they could be travelling the world or working another job. “What’s your thoughts,” she asks her followers. “Should he be fired?” Below the video, her caption reads: “Is his employer overbearing or did he mess up? #techlayoffs #overemployed #programming.” According to Judge, this clip was not intended to encourage such behaviour but rather to start a conversation. “Is there an oversaturation of job types that aren’t needed for a full 40-hour week role, or did people give up on their career?” she says. “That’s just one example of how I use dramatic ideas to challenge what needs to change for the future.”

Judge’s content speaks to a phenomenon the late ethnographer David Graeber wrote about in Bulls*** Jobs (2018), a book centred on the premise that myriad jobs have little to no social value and even their holders cannot justify the profession’s existence. For Graeber, these play a key role in the glut of unnecessary work that prevents economist John Maynard Keynes’ prediction of a 15-hour working week coming true. While most corporate TikTokers rarely adopt such strong views, it’s not uncommon to see them toying with diluted versions, nitpicking the time-wasting bureaucracies endemic to many corporate roles.

Henry Nelson-Case, or @thatcorporatelawyer as he’s known on TikTok, uses his videos as tongue-in-cheek jibes at outdated practice. From the pointless requests to “jump on a call” when it could just be an email, to running errands in work hours, his sketches are not about the redundancy of corporate jobs in themselves, but instead changes that companies could make. “Contrary to a lot of the comments I get on TikTok, I am actually a fully qualified lawyer and work hard,” he tells me. “I’m not always swanning the supermarkets or going on walks at 11am. I think the key point is that there is a real shift in how we work and prioritise our time, especially post-pandemic. The traditional nine-to-six working day is not always the most productive way of working for many.”

To Nelson-Case’s point, salaried jobs can go through quiet periods, when perhaps a kinder manager might let you clock off early, or busy periods, when every second counts and idle small talk falls by the wayside. If working conditions are to match this, that means customising them to the person who would prefer to blitz their work in the first few days of the week and the person who likes to amble along, peppering their day with catch-ups, coffee and cake.

The latter finds its hellish pinnacle in one clip by Abi Clarke (@abiclarkecomedy), where characters Jill and Tracey get trapped in an endless loop of office niceties, going back and forth with “Morning! Good, you?” ad infinitum. It makes funny viewing but does pose the existential question of how many working hours we spend actually grafting and how many involve listening to Carol from marketing divulge every inane detail of her weekend. Private sector? Efficient? Not quite.

And it shows. Hot on the heels of the economic downturn – as well as consistently failed promises that working hard, going to university and biding your time pays off – many young people would rather cut the crap, all too aware that middle-class martyrdom is just that. “By this point, our BS-meter is almost inherent,” says Connor Blakley, CEO of YouthLogic, a Gen-Z-led marketing agency. “As young people encounter more needless systematic bureaucracy, they will continue to instinctively share and call out stupid corporate behaviour.”

Some would call them snowflakes, but this desire for work to work for you is admirable. Sara Bimo, a doctoral researcher at York University in Toronto, says she’s observed an exceptional awareness of labour exploitation and its bureaucratic cloaks among millennial and zoomer generations. “[It] can manifest as a mixture of pessimism and absurdism surrounding the infrastructures of daily corporate life,” she says. “[It] allows these workers to deconstruct and, thus, render meaningless structures of corporate control.”

Granted, this particular jostle with corporate culture wasn’t the revolution Karl Marx envisioned, but it’s still a form of worker resistance, one that does the best it can with its native means. As it goes, TikTok users are often aware of its flaws and pay heed to these. For Goldsmiths University doctoral researcher Andreas Schellewald, he recognises that the trend could encourage employees to use hacks to manage the workplace, inadvertently placing the responsibility on themselves rather than encouraging a radical rethink. “But at the same time, if you look at the wider debates, I feel that this is more a phenomenon tied to a growing demand for systemic change of our work culture,” he adds. There you have it. The revolution will not be televised, but it will be TikTok-ed.