The world's oldest landmarks still attracting the crowds today

Ancient attractions

Sorin Colac/Alamy

Stunning architecture, feats of incredible engineering and beautiful pieces of art from countless cultures: it should come as no surprise that many of the world's most popular tourist destinations are ancient wonders. Whether they’re cities and castles or temples and tombs, visitors flock to them in droves and leave filled with awe.

Read on to explore some of the world's oldest places that still draw huge crowds, arranged from youngest to oldest…

1648: Taj Mahal, Agra, India

R.M.Nunes/Shutterstock

When Mumtaz Mahal, wife of the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan, died giving birth to their 14th child in 1631, her grief-stricken husband set out to build her a mausoleum so beautiful that she would be remembered forever. The result was one of the world’s best-known buildings. The Taj Mahal cost a fortune and took 20,000 workers 22 years to complete, but the five million or so people who visit the site every year would probably argue that it was worth it. Especially when seeing the white marble dome and accompanying minarets glint in the sun, or walking in the lush gardens by the long reflecting pool.

c.1450: Machu Picchu, Peru

Sorin Colac/Alamy

Nowhere evokes the ancient Inca civilisation more than the citadel of Machu Picchu. High in the Andes at 7,700 feet (2,350m) above sea level, the ruins – with palaces, temples, houses and cascading agricultural terraces – blend with the curves of the landscape. The Incas' engineering expertise is clear to see too, thanks to sophisticated irrigation systems and masterful stonework. The emperor Pachacuti possibly built Machu Picchu as a royal retreat, and its remoteness meant it was spared the attention of the conquering Spanish in the 16th century. More than two million people marvelled at the mountaintop monument in 2023.

1420: Forbidden City, Beijing, China

travellinglight/Alamy

This 178-acre complex in the heart of Beijing is a forest of wooden temples and vibrant oranges and reds. It is easy to see why many of the 16 million annual visitors spend the whole day here, feeding off the sense of history, tradition and ritual. The unmissable sights start with the Hall of Supreme Harmony, with its lavishly decorated Dragon Throne, and continue through the Palace of Heavenly Purity and the Imperial Garden. Beginning in 1420, the Forbidden City was the residence of the emperors of China for 500 years. Now it's home to the Palace Museum, which contains around 1.8 million artefacts.

1248: Cologne Cathedral, Cologne, Germany

Roy Conchie/Alamy

A Gothic masterpiece, Cologne Cathedral dominates the city skyline and tops the list of Germany's most popular landmarks with more than six million annual visitors. It was a long time coming, however. Construction began in 1248 and, after periods of abandonment, it would only be completed in 1880. Its imposing twin towers measure 515 feet (157m) and take 533 steps to climb. On ground level, the cathedral houses religious treasures like the Shrine of the Three Kings, a bejewelled tomb said to contain the bones of the three wise men of the Nativity.

1238: Alhambra, Granada, Spain

Art Kowalsky/Alamy

The Andalusian city of Granada is well-known for its Moorish history and architecture, and nowhere is this more evident than the Alhambra. The palatial citadel sits perched on an outcrop above the city and is a monument to Moorish artistry, with intricate carvings and colourful tiling all around. It was constructed by the last Islamic dynasty in western Europe, the Nasrids, but when they were expelled in the 15th century the complex got a Renaissance-style makeover. We're lucky the fortress is still standing – it was occupied and nearly destroyed by Napoleon’s armies in the early 19th century.

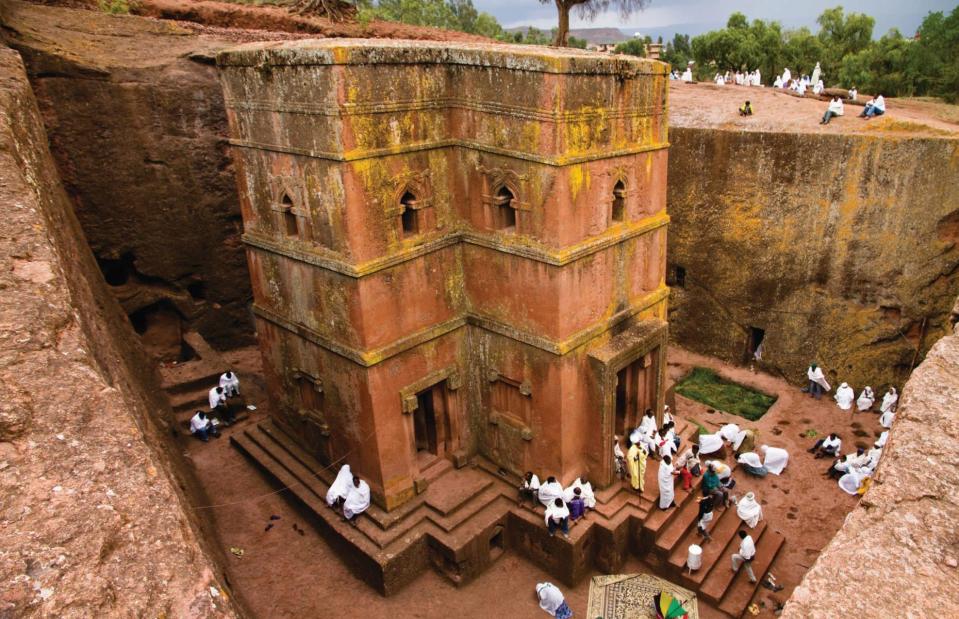

1200s: Lalibela, Ethiopia

imageBROKER.com GmbH & Co. KG/Alamy

Built to be a 'New Jerusalem', the town of Lalibela in northern Ethiopia is revered by the country's Orthodox Christians for its 11 churches. These are not normal churches, however – each has been hewn from the rock, dug out of the ground in one piece. The best known is the Church of St George, which is in the shape of a cross and can only be accessed by a narrow canyon that leads down to the front door. An early 13th century king is generally credited with creating the churches – an attempt to build a Jerusalem in his homeland at a time when pilgrimages to the Holy Land were too dangerous.

1163: Notre-Dame, Paris, France

JOHN KELLERMAN/Alamy

There is no finer example of French Gothic architecture than Notre-Dame. More than that, it is a symbol of Paris. The foundation stone was laid by the Pope in 1163, though the monumental building would take centuries to fully finish. As a tourist destination it used to host as many as 12 million people a year, but has now shuttered for five years since a devastating fire caused the roof to cave in and the 19th-century spire to topple. Restoration began immediately and, all going well, the cathedral will welcome the crowds once more by the end of 2024.

c.1150: Angkor Wat, Siem Reap, Cambodia

Mike Fuchslocher/Alamy

Spread across 400 acres and more than 1,000 buildings, Angkor Wat is the largest religious structure in the world. And with ornate carvings everywhere, five central towers and a perfectly square moat, it's one of the most picturesque too, attracting more than two million annual visitors. Built over several decades by King Suryavarman II, the sprawling temple complex was initially dedicated to the Hindu god Vishnu, but had turned Buddhist by the end of the century. It remains so important to Cambodia that it sits at the centre of the national flag.

1100s: Edinburgh Castle, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK

eye35.pix/Alamy

Known as 'defender of the nation', Edinburgh Castle was a key character in British royal history, and was a Scottish royal residence from at least the 11th century – Queen Margaret died there in 1093. The castle we see today dates from a bit later, and its oldest surviving section, St Margaret's Chapel, was built in her honour in the 1130s. To this day the castle houses the Honours of Scotland (the Scottish crown jewels) and the legendary Stone of Scone (a block of sandstone still used in British coronations). It also claims to be the most besieged place in Britain. It remains an active military base, and a highlight of any visit is the 'one o’clock gun', when a cannon is fired from the battlements.

c.1100: Easter Island, Chile

Panther Media GmbH/Alamy

Easter Island is a tiny speck in the Pacific Ocean 2,200 miles (3,450km) west of Chile, but it's famous around the world. Annual visitor numbers dwarf the island's 8,000-strong population, and most of them flock to see the hundreds of carved stone figures known as moai. Starting around AD 1100, the Rapa Nui people quarried huge blocks of volcanic rock and painstakingly transported them across the island to be carved and raised. This was no small feat, with each moai measuring between four and 12 feet (1.2m and 3.7m) tall and weighing tens of tonnes. Talking of feet, a common misconception is that the moai are just heads – the statues had bodies too, but many were buried over time.

1070s: Tower of London, London, England, UK

incamerastock/Alamy

A fortress has stood guard on the banks of the Thames for the best part of a millennium, first constructed by William the Conqueror almost as soon as he took the throne in 1066. A constant in British royal history, the Tower of London has served as a palace, a prison, a garrison, a royal mint and even a zoo. It was where the doomed Princes in the Tower disappeared, and where Anne Boleyn lost her head. Visitors still flock to explore the central White Tower, ogle the Crown Jewels and get to know the ravens. If they ever leave, the legend holds, England will fall.

c.1000: Cahokia Mounds, Illinois, USA

Matt Gush/Shutterstock

It's not one of America's most popular attractions – it’s not as shiny as Times Square or the National Mall – but Cahokia Mounds is one of the most historic sites in North America. A Native American society home to between 10,000 and 20,000 members of the Mississippian culture during the 11th and 12th centuries, the settlement contains Monks Mound – the largest prehistoric earthwork in the Americas. More than 100 earthen mounds were made in total, with clearly defined ceremonial and residential areas. Cahokia was largely abandoned in the 14th century for reasons that remain unknown.

c.850: Borobudur Temple, Indonesia

GRANTROONEYPREMIUM/Alamy

In 1814, an Englishman named Stamford Raffles – who would be remembered as the founder of modern Singapore – made a discovery while posted on the Indonesian island of Java. Buried for centuries under volcanic ash was an ancient monument, which would turn out to be the largest Buddhist temple in the world, covering 26,900 square feet (2,500sqm). Shaped like a pyramid, the climb up Borobudur represents the spiritual journey to enlightenment. At the top is a central dome surrounded by 72 statues of the Buddha, each inside smaller domes known as stupas.

786: Mosque-Cathedral of Cordoba, Cordoba, Spain

Sean Pavone/Alamy

There are plenty of examples of mosques that became churches or vice versa, but this one has a twist. Built in the 8th century as a mosque, it greatly expanded over the years to become one of the largest Islamic buildings in the world. Then, in 1236, the Islamic Moors were kicked out of Cordoba and the Roman Catholics took control. Eventually, the decision was taken not to destroy the mosque, but simply build a grand Christian cathedral in the middle. It makes for a stark change of scenery for the two million people who visit every year.

732: Tikal, Guatemala

Leonid Andronov/Shutterstock

In the rainforests of Guatemala are the ruins of one of the great sites of Maya civilisation. Tikal was settled during the first millennium BC but reached its peak during the Late Classic Period (AD 600-900). This was when by far its most impressive pyramid was constructed, traditionally dated to AD 732: the magnificent Temple of the Great Jaguar. It's sometimes known by its less imaginative name, Tikal Temple I. Among the thousands that trek to the ruins every year there are bound to be some Star Wars fans, since the ruins were used to represent the rebel base in the 1977 movie, A New Hope.

700s: Ellora Caves, Aurangabad, India

Mazur Travel/Shutterstock

For centuries this sprawling network of 34 rock-cut temples has been a place of worship for Hindus, Buddhists and Jains. The caves span an enormous period – from the Buddhist shrines cut in 200 BC to Jain temples from AD 1000 – and are carved from volcanic basalt. They're decorated with detailed sculptures and paintings that have survived remarkably well. The imposing 8th-century Hindu temple, Kailasa, is perhaps the most impressive. It's less a cave than a 98-foot-tall (30m) building hewn into the ground, built by the removal of roughly 200,000 tonnes of rock.

691: Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem

Abdullah Durman/Shutterstock

Although visitors are limited – as a sacred site, non-Muslims are not permitted to enter – simply gazing at the gold-plated dome of this shrine is enough to take your breath away. Built between AD 688 and 691, the Dome of the Rock is at the centre of the Temple Mount complex in Jerusalem, a deeply holy place for Jews and Muslims. The rock in question is believed to be where Abraham prepared to sacrifice his son Isaac in the Bible, while in Islamic tradition it's where the prophet Muhammad ascended to heaven. The gold roof, however, is a more modern feature, added in the 20th century. In 1993 it was redone thanks to a multi-million-dollar donation from the King of Jordan.

645: Senso-ji Temple, Tokyo, Japan

Luciano Mortula/Alamy

One of Tokyo's best-known and most visited sites – often pulling in a staggering 30 million visitors in a year – this Buddhist temple is dedicated to Kannon, goddess of mercy. According to legend, its origins go back to AD 628, when a golden statue of the deity was pulled out of a river by two fishermen, leading to the construction of the temple in AD 645. Though honoured as Tokyo’s oldest shrine, Senso-ji Temple was actually destroyed by bombing in the Second World War, and what we see today is a 1950s reconstruction.

600s: Chichen Itza, Mexico

Konstantin Kalishko/Alamy

Founded around the 7th century, the ancient city of Chichen Itza was one of the central hubs of the Maya civilisation, and flourished thanks to several large cenotes that gave residents easy access to water. Today the main attraction is a nine-tiered pyramid called the Temple of Kukulcan (a serpent deity), which is often known by its Spanish name, El Castillo. The site is a thriving tourist destination all year round, but the spring and winter equinoxes are the most popular times to visit. On those days, the afternoon sun casts a shadow over El Castillo that resembles the snake god itself crawling down the steps.

532: Hagia Sophia, Istanbul, Turkey

Efrain Padro/Alamy

Built by the Byzantine emperor Justinian at the height of the Byzantine Empire's power, the Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque has been one of the world's best-known buildings for most of the last 1,500 years. The crowds come for the unique architecture, the blend of Christian and Islamic iconography and the gorgeous golden mosaics. When first built – in just six years from AD 532 to 537 – it was a Christian cathedral. It became a mosque in the 15th century, a museum in the 20th century and finally, in 2020, a mosque once again.

477: Sigiriya, Sri Lanka

travelwild/Shutterstock

Building a fortress on a vertical pillar of rock reaching 600 feet (180m) above the ground seems like a surefire way to stay safe from enemies. That’s what 5th-century ruler Kashyapa I hoped when he built Sigiriya (meaning 'Lion Rock'), complete with water gardens fed by an ingenious irrigation system, on this flat-topped summit. He even designed it in the shape of a lion, but he was defeated in battle in AD 495 and his fortress fell into ruin. Today, its dramatic setting makes it a beloved tourist spot, attracting around a million visitors a year.

218: Volubilis, Meknes, Morocco

funkyfood London - Paul Williams/Alamy

Set just off the road between Fes and the coastal cities of Casablanca and Rabat, we're sure plenty of tourists drive past Volubilis every year without realising what they're missing out on. The Roman ruins are only partly excavated but have already revealed a host of treasures, including exquisitely well-preserved mosaics that are still in situ. Rome took control of the area in the 1st century AD but the structures seen today came later, such as the Capitoline Temple built in AD 218. Volubilis remained an important city after the Romans left, and its treasures were preserved by the desert until excavations began in the early 20th century.

c.100: Teotihuacan, Mexico

Cosmo Condina/Alamy

We don't really know when Teotihuacan was founded, so our date is very much an estimation, but the Mesoamerican city peaked around AD 500. At this time its population numbered between 125,000 and 200,000 people, making it one of the largest cities not only in the Americas, but in the world. And yet it remains unclear who its inhabitants were. Teotihuacan predates the Aztecs and was in ruins when they arrived centuries later, but they gave the city its name, meaning 'the place where gods were created'. For the millions of annual visitors it's easy to see why – the site is dominated by the still awe-inspiring Pyramids of the Sun and Moon.

80: Colosseum, Rome, Italy

Nataliya Hora/Alamy

For more than three centuries the Colosseum sated Rome's bloodlust for gladiatorial games, but even though it could accommodate a minimum of 50,000 spectators, it sees even higher demand today. In 2023 alone, the Colosseum welcomed more than 12 million visitors. Construction began in AD 72 under Emperor Vespasian and was finished eight years later under his son, Titus. Time hasn’t always been kind – neglect and earthquakes caused a huge section of the wall to collapse – but the sheer scale of the structure is still obvious to all.

79: Pompeii, Campania, Italy

robertharding/Alamy

In AD 79 the eruption of Mount Vesuvius engulfed the Roman cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum in volcanic ash and pumice. Those who did not escape were killed almost instantly, and were entombed for nearly 2,000 years alongside the city itself. When excavations eventually got underway, cavities in the ash were discovered where bodies had been frozen in time, allowing for plaster casts to be made of the dead. Pompeii has been a popular tourist destination ever since and today around two and a half million people a year wander the site, alongside archaeological teams still meticulously working through the rubble.

30s BC: Masada, Israel

photosounds/Shutterstock

Reaching this fortress atop a rocky plateau in Israel overlooking the Dead Sea requires a tricky ascent on foot – or a much more relaxing cable car. Once there you can explore what remains of the citadel constructed by Herod the Great, King of Judea from 37 BC to AD 4, including two palaces, aqueducts and large defensive walls. But Masada has become more than just a historic site. Legend holds that when the Romans besieged the fortress in the 1st century AD, the Jewish defenders took their own lives rather than be captured. Historical accuracy aside, their bravery and sacrifice made Masada a symbol for the Jewish people.

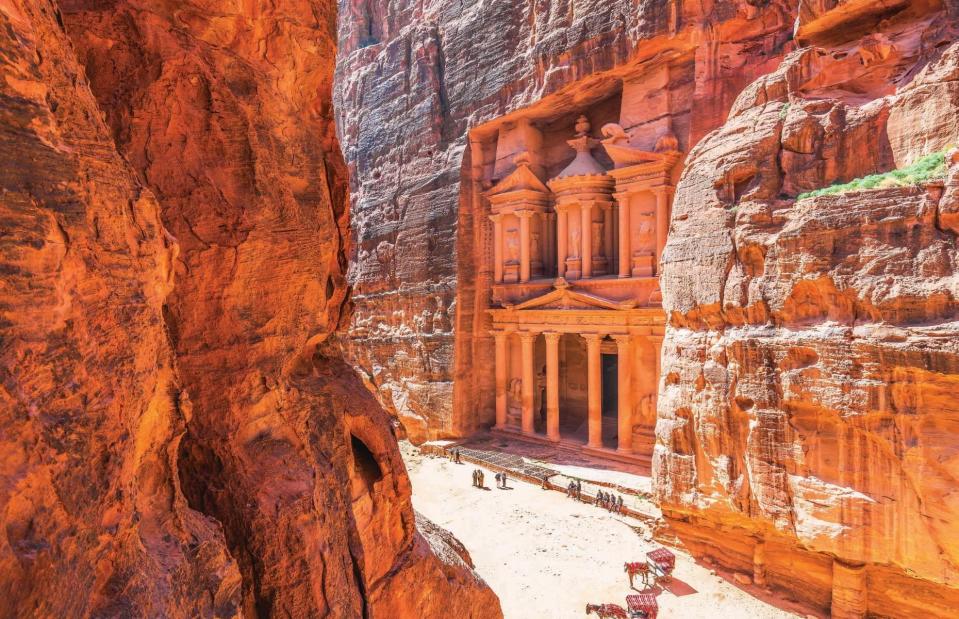

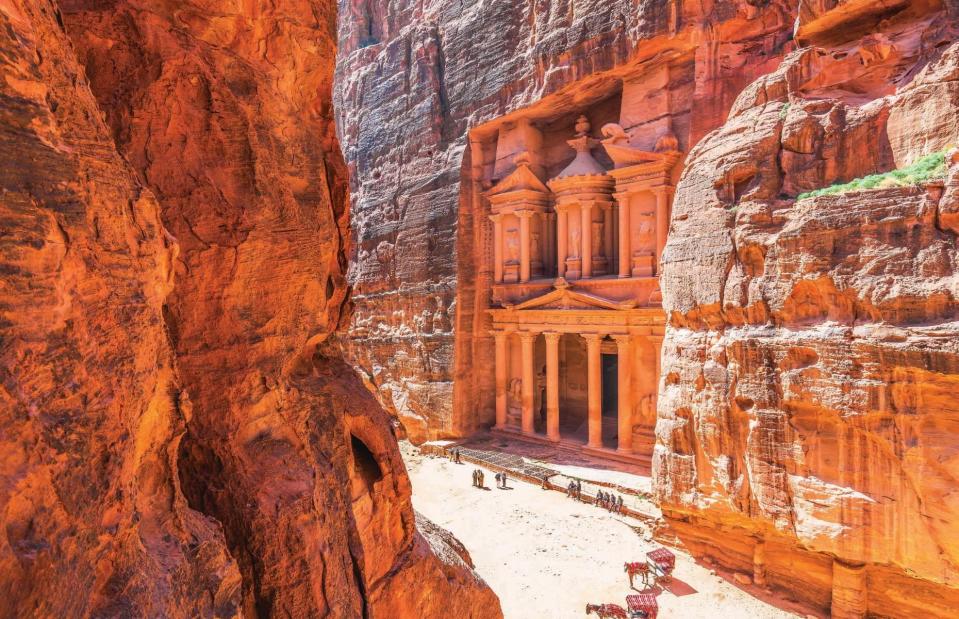

200s BC: Petra, Jordan

Sorin Colac/Alamy

Petra makes quite an entrance as you walk through a narrow crack in the cliffs, which open to reveal Jordan's most precious ancient landmark, the rock-cut tomb of Al-Khazneh (the Treasury). The so-called Rose City was the crowning achievement of the Nabataeans, a nomadic desert people who carved the buildings out of the very sandstone of the cliffs. Their creations were influenced by other cultures – Al-Khazneh’s columns, for instance, resemble the Greek style. Petra housed as many as 30,000 people and thrived in ancient times as a trading crossroads in the desert. Today, it is everyone's first priority when arranging a trip to Jordan.

200s BC: Great Stupa, Sanchi, India

Dmitry Rukhlenko/Shutterstock

It's not the most visited landmark on this list – with tourists numbering hundreds of thousands, not millions – but Sanchi contains some of the oldest and finest examples of Buddhist art and architecture in India. The centrepiece is the Great Stupa, a domed structure built for meditation and to house relics. Erected in the 3rd century BC, it was expanded and repaired over the next two centuries, reaching 54 feet (17m) in height and 120 feet (37m) in width. It is approached via lavish gateways, or toranas, decorated with scenes from the life of the Buddha.

200s BC: Great Wall of China, China

Li Ding/Alamy

The first thing to know if you’re among the 10-million-plus annual visitors to the Great Wall is that it was never a conventional, single-structure wall, but a series of fortifications. Much of it has now been reclaimed by nature, and no, whatever you might read on social media, it can’t be seen from space. The first emperor of China, Qin Shi Huang (221-210 BC), was the first to order that existing sections of defensive wall be connected into a single system. And it was the Ming dynasty that erected the Great Wall as we know it today between the 14th and 17th centuries AD, hoping it would put a stop to Mongol invasions. Unfortunately for the Ming, it didn’t.

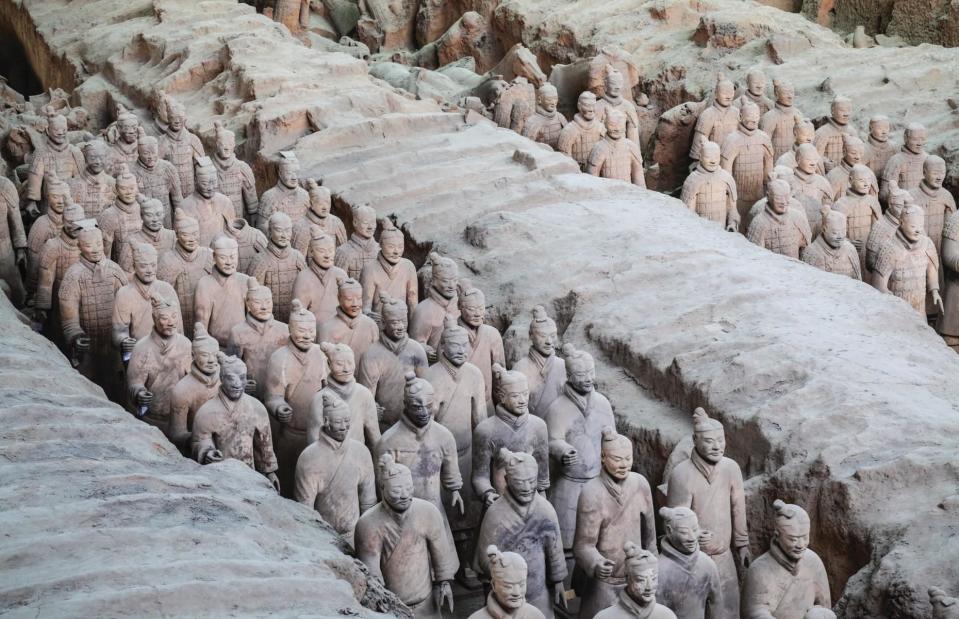

210 BC: Terracotta Army, Xi'an, China

Zoonar GmbH/Alamy

China's first emperor, Qin Shi Huang, died in 210 BC desperate to achieve immortality. He'd spent decades preparing an enormous mausoleum, which he filled with an army that would serve him in the afterlife. These terracotta warriors were arranged in battle formation with horses, chariots and weapons, while each had unique clothing and facial expressions. Though famous now for looking reddish-brown, the warriors were brightly coloured, but exposure to air caused the paint to flake. The site was only found in 1974, so only 2,000 of an estimated 8,000 figures have been unearthed, while the emperor’s tomb has never been opened at all.

447 BC: Acropolis, Athens, Greece

Sergey Borisov/Alamy

We have the great statesman Pericles to thank for the Acropolis that we see today, and the magnificent temple complex that he commissioned has become the ultimate symbol of the Athenian golden age. There’s the Propylaea (ceremonial gateway), and the smaller temples of Erechtheion and Athena Nike, but it is the Parthenon that really draws the crowds – so many that the site now has a visitor cap of 20,000 a day. The monument is perhaps the most photographed ancient landmark in the world, and you can still see all 46 of its outer columns.

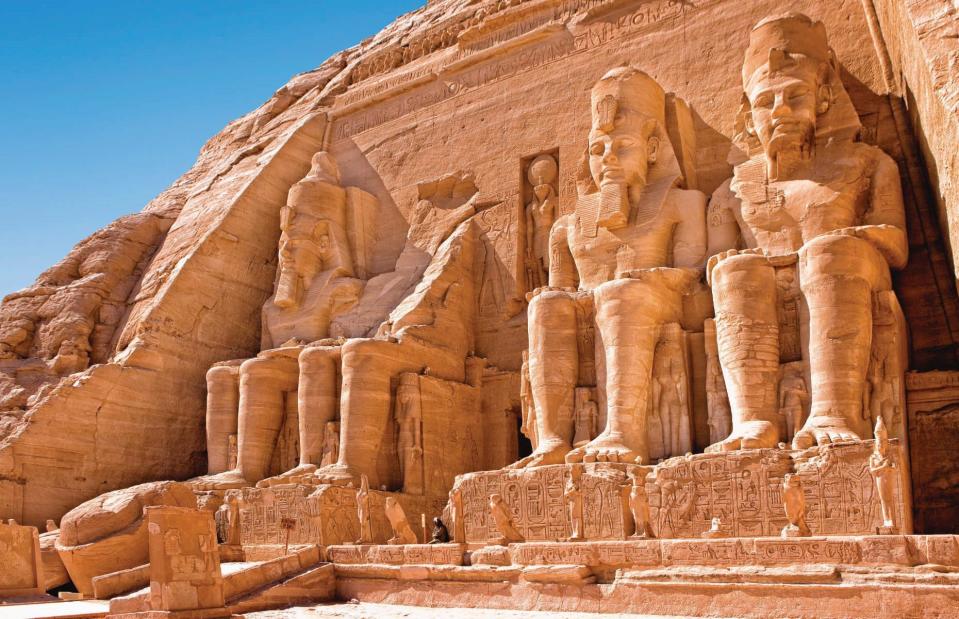

1264 BC: Abu Simbel, Egypt

Art Kowalsky/Alamy

Pharaoh Ramesses II, who reigned from 1279 to 1213 BC, left a lot of monuments behind, but Abu Simbel is surely the most breathtaking. Set in Egypt's far south, the four 65-foot-tall (20m) statues – all of the man himself – are well worth the trip all on their own. He also built a smaller temple for his favourite queen, Nefertari, and let her have two of the six statues outside (you can guess who the other four depict). The entire site was saved from the rising waters of the Nile in the 1960s when, in a staggering feat of engineering, the entire monument was moved to higher ground.

c.1900 BC: Knossos, Crete, Greece

Georgios Tsichlis/Alamy

The Minoan civilisation flourished on the Mediterranean island of Crete from around 5,000 years ago, and Knossos was its capital and home to a magnificent palace. According to myth, it was where the Greek hero Theseus braved the labyrinth and fought the Minotaur. Today, every eye will be drawn to a section of wall with three red columns and a painting of a bull. It looks a bit too good to be true, and it is: when Knossos was excavated by British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans in 1900, he reconstructed sections according to his own assumptions using modern techniques. That doesn’t seem to upset the 5,000 tourists a day that visit during summer, however.

2500 BC: Stonehenge, England, UK

Andrew Roland/Alamy

In 1915, a man named Cecil Chubb paid £6,600 (£565,000/$718,000 today) at auction for a unique lot: Stonehenge. He then gifted the ancient landmark to the nation. The legendary stone circle has stood on Salisbury Plain for around 4,500 years, just not in one piece. There used to be a complete outer ring of monumental sarsen stones weighing around 25 tonnes each, with an inner ring made up of bluestones, which were smaller but came from some 150 miles (240km) away. The monument's true purpose remains a mystery, but it was aligned with the summer and winter solstices, suggesting some form of ritual use.

c.2600 BC: Pyramids of Giza, Cairo, Egypt

robertharding/Alamy

Driving through Cairo is a loud and chaotic experience, which makes the quiet dignity of the pyramids even more striking when the city thins out to leave the spectacular sight of the last of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World still standing. That said, with more than 14 million visitors a year, the pyramids can still feel busy. Built around the 26th century BC as the tombs of pharaohs Khufu, Khafre and Menkaure, they tower over the nearby Sphinx. The Great Pyramid alone contains 2.3 million limestone blocks and, at 481 feet (147m), was the world's tallest manmade structure for nearly four millennia.

3200 BC: Skara Brae, Orkney Islands, Scotland, UK

imageBROKER.com GmbH & Co.KG/Alamy

It is strange to think while looking at Skara Brae, with the Bay of Skaill in the background, that it was inland when it was first built more than 5,000 years ago. Yet the sea serves as a reminder of how fortunate we are that Skara Brae has survived at all. The cluster of nine Neolithic houses, each with beds, hearths and drainage, spent centuries hidden under sand dunes, and was only revealed by a fierce storm in 1850. The village now attracts more than 100,000 people a year – not bad for the remote Orkney Islands – who can see original stone furniture and artefacts including tools, jewellery and dice.

3200 BC: Newgrange, County Meath, Ireland

MNStudio/Shutterstock

It's hard to pick what's most impressive about Newgrange. It could be the sheer scale of the grass-topped Neolithic tomb – 279 feet (85m) in diameter and 43 feet (13m) high. Or it could be the fact that it's over 5,000 years old. Or it could be the beautiful megalithic art carved onto the kerbstones ringing the monument and standing at its entrance. For many, the allure of Newgrange is captured best on the winter solstice, when morning light perfectly shines through the opening above the entrance and illuminates the passageway for 17 minutes. Thousands of people enter a lottery every year for the few dozen tickets that get you into the passage that morning.

3600 BC: Ggantija, Gozo, Malta

Viliam.M/Shutterstock

The second oldest known religious structures in the world, the two Ggantija temples date from as early as 3600 BC, and make up the most notable historic site in Malta. The two conjoined temples face southeast and are made up of apses, or semicircular niches, with pillars inside that may have served as altars. The remains of figurines and animal bones suggest they were used for ceremonial purposes, perhaps animal sacrifice. The visitor centre displays some of the carvings discovered at the site, most notably the 'fat ladies' figurines.

4500 BC: Cairn of Barnenez, France

Hemis/Alamy

Dubbed 'the Prehistoric Parthenon', the Cairn of Barnenez is one of the oldest surviving megalithic monuments in Europe – a wonder of Neolithic engineering. And it sits in an idyllic setting too, overlooking the Bay of Morlaix in northern Brittany. The cairn was erected between 4500 and 3900 BC and is 230 feet (70m) long and nearly 26 feet (8m) high. Inside are two sets of tombs across 11 chambers, or dolmens, from two separate periods of construction. The monument was almost lost in the 1950s when it was rediscovered while being used as a quarry.

9600 BC: Gobekli Tepe, Turkey

Dimitar Chobanov/Alamy

Widely considered the world’s oldest temple, found atop a rocky plateau in southern Turkey, Gobekli Tepe was erected by hunter-gatherers before they even had pottery, let alone metal tools. Yet they managed to arrange 16-foot-high (5m) megalithic stones in circular enclosures around T-shaped pillars that were decorated with carvings of animals and human figures. No traces of everyday life have been found, so it seems the Neolithic site was solely used for ritualistic purposes.

Now discover our ranking of the world's most exciting archaeological discoveries