The world’s most intact archaeological discoveries, ranked

Archaeological time machines

David Cole/Alamy

It is said that archaeology is like a window to history. But occasionally archaeologists stumble upon finds that are so well-preserved, it’s as if they've been transported through time. These finds are all strikingly intact: some survived against all the odds, some were preserved in unusual ways and some seem almost good-as-new.

Read on for our ranking of the world’s most intact archaeological discoveries – and their outsized impact on our understanding of the past...

30: Convict belongings, Hyde Park Barracks, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

ILYA GENKIN/Alamy

Hyde Park Barracks in Sydney has been many things over its 200-year history – a barracks for convicts, a hospital, a mint and a courthouse. And when archaeologists began excavating the site back in 1980 with a view to making it a museum, they discovered that a collection of sorts had been 'curated' beneath the floorboards... by convict-era rats. All told, they found over 80,000 artefacts preserved in rats' nests, including convict-era cloth, prayer books and personal treasures that would never have otherwise survived. A few mummified 'curators' (pictured) were found too.

29: Antikythera Mechanism, Antikythera, Greece

Hercules Milas/Alamy

When a group of sponge divers came across a 2,000-year-old shipwreck off the Greek island of Antikythera in 1901, they didn’t give much thought to the three pieces of corroded bronze among the recovered artefacts. But when a British science historian spotted them in an Athens museum in 1951, he recognised them as part of an ancient Greek 'computer' used as an astronomical calendar. The mechanism has been called "the most complex piece of engineering to have survived from the ancient world", and was intact enough that scientists used computer modelling to recreate its complex gear system in 2021.

28: Etruscan and Roman statues, Italy

Courtesy of the Italian Ministry of Culture

Preserved in mud beneath an ancient bathhouse in San Casciano dei Bagni in Tuscany, these 2,300-year-old Etruscan and Roman statues were only discovered in 2022, but they're already rewriting history. It's thought that the detailed statues of divine figures and human organs were immersed in thermal waters in a sort of healing ritual. They date from a time when the region was transitioning from Etruscan to Roman rule, and indicate that the two cultures lived much more closely than previously thought – they may even have prayed together.

27: Grauballe Man, Denmark

GRANGER - Historical Picture Archive/Alamy

This remarkably well-preserved body was found suspended in a peat bog in Denmark in 1952 by a local peat-cutter, and was promptly christened 'Grauballe Man' after the village closest to the site. Despite being over 2,300 years old and sustaining a shovel injury during his discovery, Grauballe Man sports an impressive head of hair (dyed red by the murky bog) and stubble on his chin. Archaeologists believe he was killed and thrown into the bog as part of a ritual sacrifice. You’ll now find him resting in the Moesgaard Museum in Aarhus.

26: The lost city of Aten, Egypt

KHALED DESOUKI/AFP via Getty Images

Although excavations at the site only began in 2020, the discovery of the 'Lost Golden City' of Aten near Luxor in Egypt is already being hailed as one of the great ancient Egyptian finds of the century. Led by famed Egyptologist Dr Zahi Hawass, archaeologists have been astounded by how extensive and intact the 3,400-year-old city is, and have already uncovered three palaces, large bakeries, workshops and a cemetery. Likely built by Amenhotep III (1390-1353 BC), expect this site to move up the ranks as more incredible finds are uncovered.

25: Sir Ernest Shackleton’s whisky, Antarctica

Australian Associated Press/Alamy

In 2007 Antarctic researchers from New Zealand made a stunning discovery – a crate of whisky, each bottle wrapped in straw, tucked under the floorboards of a hut a few days' trek from the South Pole. They'd been left there by legendary explorer Ernest Shackleton after he abandoned his attempt to reach the Pole a century before. Shackleton originally ordered the whisky to bolster morale among his men. Whyte & Mackay, the company that now owns the brand Shackleton drank, extracted samples to recreate the recipe, which they have since released as Shackleton Blended Malt.

24: Venus de Milo, Milos, Greece

Reidl/Shutterstock

She may be missing her arms, but the Venus de Milo is still regarded as one of the best-preserved ancient Greek statues in existence. She was discovered in 1820 by Yorgos Kentrotas, a farmer who was retrieving stone from an old wall on the Greek island of Milos. The statue was probably created by Greek sculptor Alexandros of Antioch between 150 and 125 BC and is thought to depict Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love. She was sold to the French ambassador in Greece by Olivier Voutier, a French naval officer who helped dig her up, and she now resides in Paris in the Louvre.

23: Children of Llullaillaco, Argentina

Juan Mabromata/AFP/Getty Images

The mummified bodies of these three Incan children sacrificed 500 years ago were so well preserved by nature that archaeologists have been able to determine exactly what they ate and drank shortly before they died. The bodies were discovered entombed within a shrine near the 22,100-foot (6,739m) summit of the Argentinian volcano Llullaillaco in 1999. By analysing hair samples, archaeologists have been able to determine that the children were fed large quantities of coca leaves (from which cocaine is extracted) and alcoholic beverages, perhaps as a method of sedation.

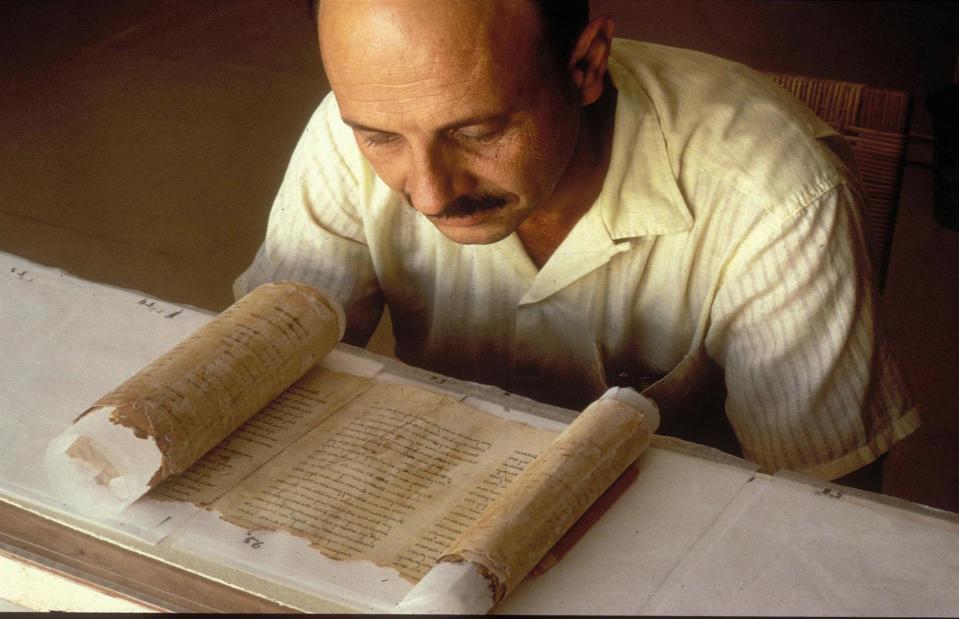

22: Dead Sea Scrolls, Israel

Zev Radovan/Alamy

Made with animal skin, papyrus and forged copper, the Dead Sea Scrolls date from between the 3rd century BC and 2nd century AD, and by rights should have been lost to the world millennia ago. Instead, these fragile documents were tucked into jars and stashed in the Qumran Caves along the northern shore of the Dead Sea until they were discovered by Bedouin shepherds in 1947. The scrolls contain the oldest known manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible, and are a fascinating insight into early Christian and Jewish religious traditions.

21: Must Farm, England, UK

PA Images/Alamy

Almost 3,000 years ago, a Bronze Age settlement in modern-day Whittlesey in England caught fire. As its inhabitants fled, their buildings burned and sank into a riverbed. It was a disastrous turn of events for the villagers, but that riverbed preserved their homes and belongings for millennia, providing modern archaeologists with a unique snapshot of life during this period. Excavations have revealed not just scorched buildings and farming implements but half-finished meals, kitchen tools and various other personal possessions.

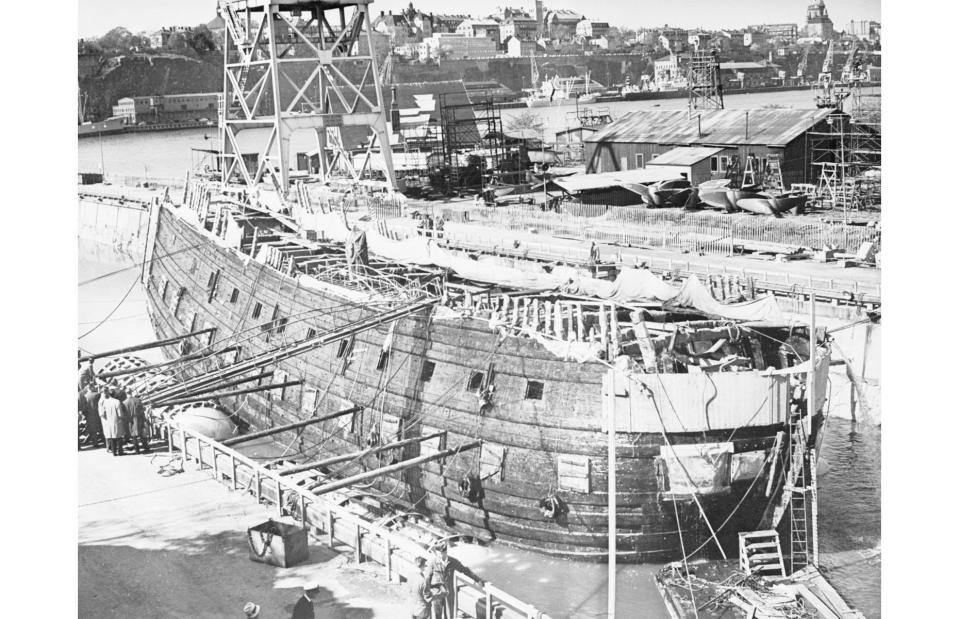

20: Vasa shipwreck, Stockholm, Sweden

Bettmann/Getty Images

One of the reasons this powerful 17th-century Swedish warship is in such good condition is that it never saw a single day of action. It sank on the day it was launched on 10 August 1628, listing in the wind and taking on water through its open gun ports. It sat on the bottom of Stockholm harbour, preserved in thick mud, for close to 333 years before it was painstakingly salvaged and brought ashore in 1961 (pictured). The Vasa Museum was then built around the vessel. Incredibly, only the outer few centimetres of the wood were degraded by bacteria.

19: Fossilised footprints, White Sands National Park, New Mexico, USA

NPS

Looking like they'd just been left behind by a family of picnickers in New Mexico’s White Sands National Park, these remarkable footprints are in fact up to 23,000 years old – and the oldest direct evidence of human presence in the Americas. The footprints were preserved in a layer of hard, ancient gypsum and are surrounded by the footprints of prehistoric mammoths, horses and even camels, showing that humans shared the area with a whole range of Ice Age animals.

18: Megalithic statues, San Agustin, Colombia

Yury Birukov/Shutterstock

When archaeologists found these extraordinary statues buried in a series of mounds in the remote mountains of Colombia, they were struck by their size, varied styles and how incredibly well-preserved they were. Over 600 figures were uncovered, each representing a god or mythical creature in styles that ranged from abstract to realist. UNESCO says the statues reflect the "creativity and imagination of a northern Andean culture that flourished from the 1st to the 8th century AD". In 1771, Spanish Monk Juan de Santa Gertrudis wrote that he believed they were carved by the devil.

17: The Venus of Hohle Fels, Germany

mauritius images GmbH/Alamy

Discovered in a cave in southwestern Germany in 2008, this incredibly well-preserved 2.36 inch (6cm) figurine has been dated to be between 35,000 and 40,000 years old. Carved from ivory, it's thought to be the oldest depiction of the human form from prehistoric times ever found, and, along with the flute made from a vulture bone found beside it, suggests that the local Palaeolithic culture had an understanding of not only figurative art but music as well.

16: Staffordshire Hoard, England, UK

Marco Secchi/Alamy

Discovered by a metal detectorist in a field in England in 2009, the Staffordshire Hoard is remarkable in many ways. Consisting of over 4,000 individual items, it is the largest hoard of Anglo-Saxon gold and silver metalwork ever found. It single-handedly increased the number of Anglo-Saxon artefacts discovered in England by 60%, and was valued at around $4.2 million (£3.3m). Perhaps the most extraordinary thing about the horde was its level of preservation. As you can see here, apart from a little mud, the 7th-century jewellery looks almost good as new.

15: Borobudur, Indonesia

Adel Newman/Alamy

The colossal stone temple of Borobudur in Java is the largest Buddhist Temple in the world. It was built between AD 778 and 850 but was covered by ash from around the year AD 1000. Local stories led the colonial officer Stamford Raffles to the site in 1814, but it was excavations by a team of Dutch archaeologists in 1907 that properly revealed the awesome majesty of its stepped platforms, miniature bell-shaped domes and intricate carvings to the world.

14: Sanxingdui gold mask, China

Imago/Alamy

Archaeologists have been uncovering extraordinary artefacts in a sacrificial pit in Sanxingdui in China’s Sichuan province ever since it was first discovered by a farmer in the late 1920s. But the most incredible and best-preserved item was only found in 2021: a surprisingly intact mask made of 84% gold and estimated to be 3,000 years old. It is believed to have been worn during sacrificial rituals and would have weighed close to a pound (0.4kgs). The souvenir fridge magnet, seen here with the original mask in Sanxingdui Museum, weighs considerably less.

13: Augustus of Prima Porta, Rome, Italy

Megan Kwan/Shutterstock

If the Venus de Milo is the best-preserved statue the ancient Greeks left behind, then Augustus of Prima Porta might just fill that niche for the ancient Romans. Clearly inspired by Greek sculpture – perhaps even by a specific Greek statue – it was discovered by archaeologists in 1863 in the ruins of a villa once owned by Livia, Augustus's wife. A giant of history, Augustus was ancient Rome's first emperor, and is depicted here addressing his troops in full imperial glory. His breastplate is in particularly good nick, and bears a scene showing a foreign king submitting to Roman authority.

12: Palace of Knossos, Crete, Greece

Hugh Olliff/Alamy

While there is some debate as to who actually 'discovered' the ancient Minoan capital of Knossos in Crete, there’s no denying who excavated it and first revealed its wonders. British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans bought the tract of land it was located on, started digging in 1899 and, a year later, unearthed palace ruins covering 5.5 acres. The complex floor plan suggests that it could have been the real-life inspiration for the labyrinth associated with the legendary King Minos and his mythical minotaur. Today the site is the second most popular attraction in Greece after the Acropolis in Athens.

11: Rosetta Stone, Egypt

M Ramírez/Alamy

While not completely intact – it was once part of a larger slab – the Rosetta Stone remains clearly legible and is one of the most important archaeological discoveries ever made. Uncovered by Napoleon Bonaparte’s soldiers while they were working on a fort in the Nile Delta in 1799, the stone dates back to 196 BC and is inscribed with a royal decree issued by priests on behalf of Ptolemy V. The decree was written in ancient Greek, Egyptian demotic script and hieroglyphics, helping French Egyptologist Jean-Francois Champollion to finally fully decipher the Egyptian hieroglyphic language in 1822.

10: Gobekli Tepe, Turkey

Ali Kabas/Alamy

Before Gobekli Tepe was discovered, historians would have told you that its T-shaped pillars shouldn’t even exist, let alone be in such good condition. Revealed by German archaeologist Klaus Schmidt in 1994, they are the world's oldest example of monumental architecture – an integral part of a 'temple' built at the end of the last Ice Age sometime between 9600 and 8200 BC. Furthermore, the pillars are carved with images of wild animals, providing insight into the way of life of the prehistoric people of Upper Mesopotamia. These hunter-gatherers in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic age seem to have had a sophisticated understanding of architecture and construction.

9: Sutton Hoo, England, UK

Oli Scarff/Getty Images

The British Museum calls Sutton Hoo the richest intact early medieval grave in Europe, and it’s hard to disagree. When landowner Edith Pretty and amateur archaeologist Basil Brown began excavating a network of mysterious mounds on Pretty's Suffolk estate in 1939 they uncovered a beautifully preserved Anglo-Saxon burial ship laden with treasure. It is believed to have belonged to King Raedwald, a 7th-century ruler of East Anglia, and included jewellery, Byzantine silverware and an incredibly rare warrior’s helmet (pictured) that has become the symbol of the find.

8: Trojan War mosaic, Syria

LOUAI BESHARA/AFP via Getty Images

An exceedingly well-preserved 1,600-year-old Roman mosaic is the last thing you’d expect to discover in the midst of a war-torn nation, but that’s exactly what archaeologists found in Rastan in northern Syria in 2022. They were excavating in an area that the government had only recently seized back from rebel forces and came across this exquisite 1,300-square-foot (120sqm) art piece depicting the Trojan War. Constructed in the Roman era, the mosaic shows soldiers beside mythical Amazons said to have fought with the Trojans.

7: World’s oldest intact shipwreck, Bulgaria

Courtesy of EEF/Black Sea Map

In 2018 a joint English-Bulgarian team mapping the floor of the Black Sea made an astounding discovery – the wreck of a Greek merchant ship, dating back more than 2,400 years, lying on its side off the Bulgarian coast. More than 6,560 feet (2,000m) down, the ship is astonishingly well-preserved thanks to the absence of oxygen in the deep water, and has been labelled the world’s oldest intact shipwreck. Before this incredible image was taken, such ships had only been seen decorating ancient Greek wine vases.

6: Aztec Calendar Stone, Mexico City, Mexico

Frank Nowikowski/Alamy

The Aztec Calendar Stone, dating from the reign of Moctezuma II, famous for his confrontation with Spanish conquistador Hernan Cortes, is among the most intact Aztec artefacts that we have – but that hasn’t quelled speculation as to what it actually is. Scholars agree that it depicts the Aztec solar year and is decorated with carvings of Aztec creation myths. It could just be a simple calendar. But increasingly the belief is that the massive 25-tonne stone was a sacrificial altar, and that the Spanish buried it in what is now Mexico City’s main square in 1521 to discourage such practices among their new subjects.

5: Skara Brae, Orkney Islands, Scotland, UK

imageBROKER.com GmbH & Co. KG/Alamy

In 1850 a severe storm stripped the earth off the top of a knoll on the Orkney Islands in Scotland and revealed the outline of a long-abandoned village. A series of archaeological digs revealed it was the Neolithic settlement of Skara Brae, established sometime around 3000 BC. Older than Stonehenge and the Pyramids of Giza, the site is now regarded as the best-preserved group of prehistoric houses in Western Europe and possibly the birthplace of the indoor toilet.

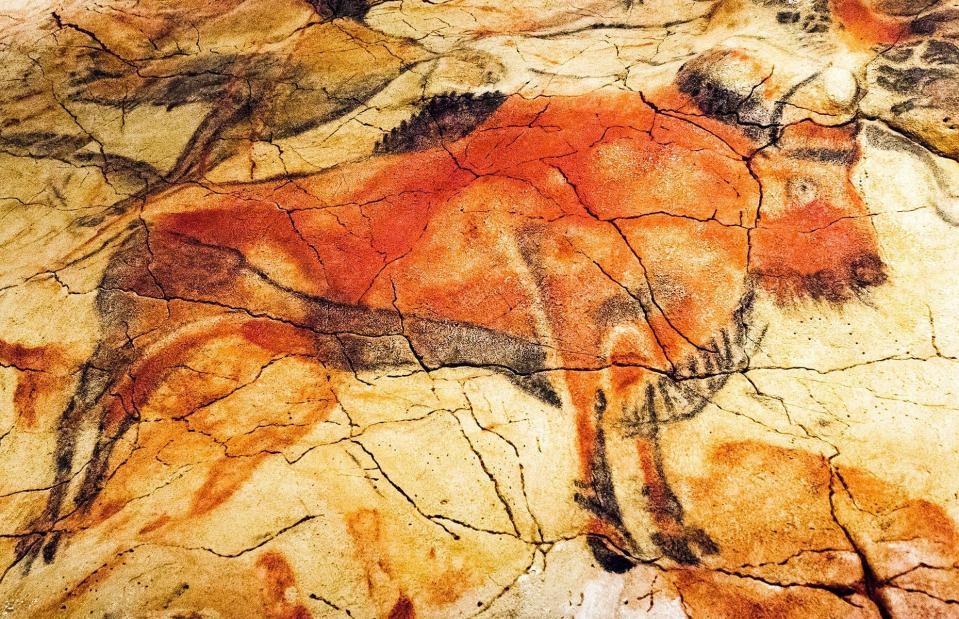

4: The cave paintings of Altamira, Spain

LAR Cityscapes/Alamy

Discovered by a nobleman's eight-year-old daughter in 1879, the Palaeolithic cave paintings found in Altamira in Spain were so well-preserved that at first experts doubted their authenticity. It is believed that a rock fall 13,000 years ago blocked humans from entering the caves – around a thousand years after the paintings were made – and the unique climatic conditions of the 951-foot-long (290m) subterranean chamber kept the art in pristine condition. Altamira is the first cave in which Palaeolithic cave art was identified and is proof that our prehistoric ancestors were capable of artistic expression.

3: Terracotta warriors, China

Izzet Noyan Yilmaz/Alamy

When farmers stumbled upon the ancient tomb of China’s first emperor, Qin Shi Huang, in Xi’an in 1974, they unwittingly uncovered one of the most incredible archaeological discoveries in history. The tomb was 'protected' by an army of 8,000 life-size clay soldiers, each one with unique facial features, hairstyle, clothing and pose. After laying hidden for over 2,000 years these stunningly well-preserved figures provide a unique insight into ancient Chinese warfare, from the designs of weapons and chariots even down to their shoes, which were very comfortable and flexible, apparently, and key to their success on the battlefield.

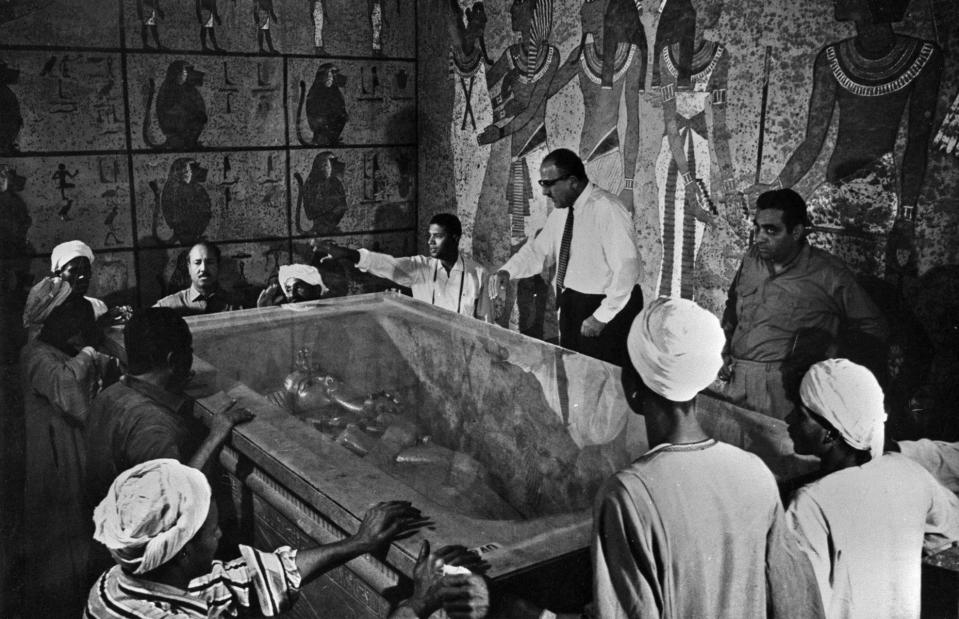

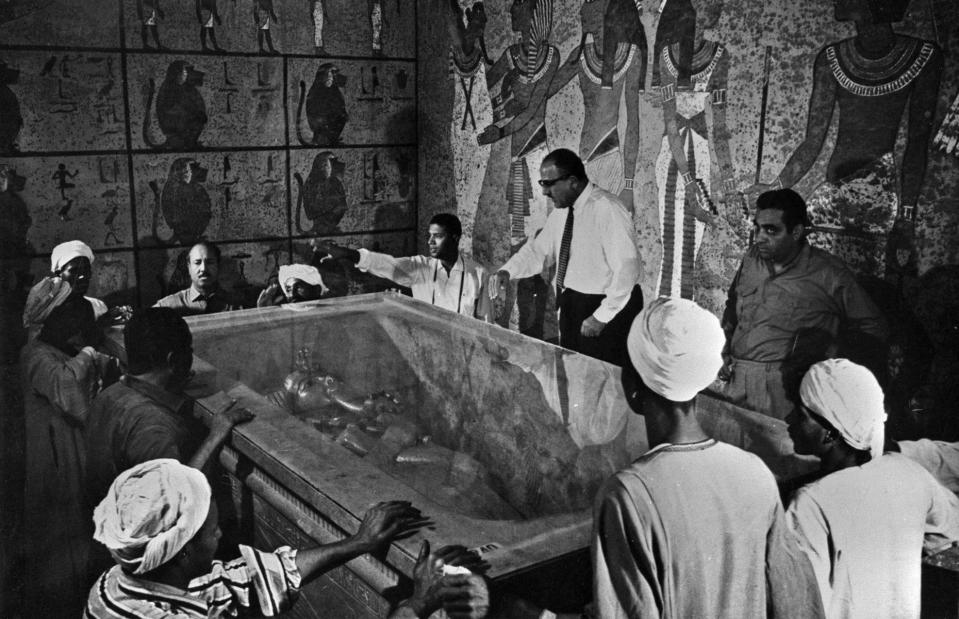

2: Tutankhamun’s tomb, Egypt

David Cole/Alamy

Discovered in 1922, the tomb of Tutankhamun in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings is still the most intact pharaoh’s tomb ever found. It had been buried under 150,000 tonnes of rock and debris thanks to other ancient building works and largely went unnoticed by tomb robbers and Victorian archaeologists. The priceless artefacts found here by Howard Carter, pictured here in the tomb observing Tutankhamun’s stunning death mask, provided unmatched insight into this moment in Egyptian history, and continue to capture the imagination of the world to this day.

1: Pompeii, Italy

Parco Archeologico di Pompei

Perfectly preserved under a 20-foot (6m) layer of pumice stone and ash after the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79, the Roman city of Pompeii is not just an architectural time capsule. The suddenness of the eruption caught the inhabitants unawares too, encasing them where they lay and offering a rich insight into daily life in this bustling city. Archaeologists have discovered everything from bedside shrines and kitchen pantries to vivid frescoes and brothels. Much of the site remains unexcavated, and new wonders are unearthed every year.

Now discover our ranking of the world's most exciting archaeological discoveries