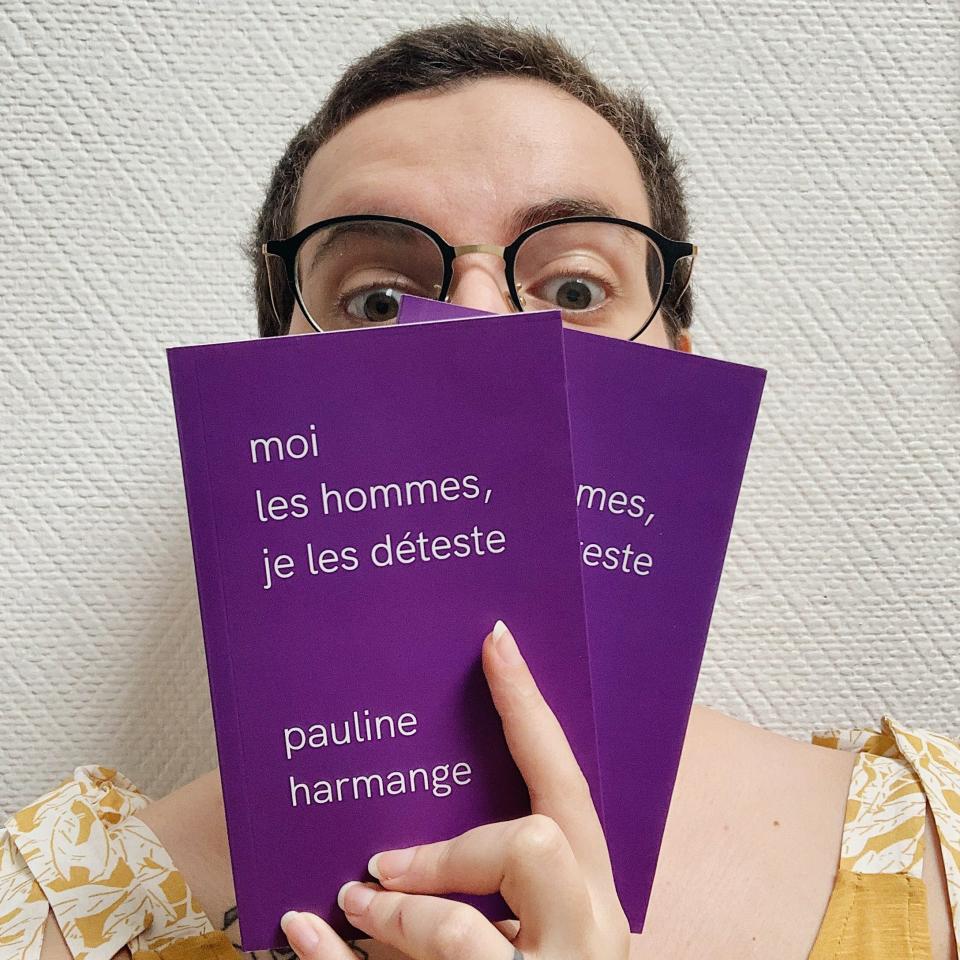

The woman who hates men so much - she wrote a bestseller about it

Pauline Harmange hates men. So much so, that the 25-year-old French author has written a book detailing and deconstructing everything she hates about 51.9 per cent of the population: I Hate Men.

“Hate will set you free,” isn’t a message we’re likely to see on a yoga t-shirt anytime soon, yet the 96-page essay – Moi Les Hommes, Je Les Déteste – that actually contains these words has sold out across France, with the first 450 copies flying off the shelves within days, a reprint of 2,500 copies sold, and “several British publishers now interested in buying the UK rights.” All thanks to Ralph Zurmély, a French government official, who has threatened to ban the book for its “incitement to hatred on the grounds of gender.”

Zurmély, who advises the gender equality ministry, even went so far as to call Harmange’s work an “ode to misandry” – amusingly a title she and her tiny publishers, Monstrograph, had considered. “And really,” Harmange laughingly insists from the Lille apartment where she’s being besieged by media interest from all over the world, “that’s a compliment.”

A little more troubling, however, is Zurmély’s assertion that if Monstrograph continue to sell Harmange’s book, the publisher would be “directly complicit in the offence and I would then be obliged to send it to the prosecution for legal proceedings.”

Before we start our interview, I feel I should declare an interest. Actually, it’s more of a bias. You see I love men. Old, young, tall, small, fat or thin: they’re up there with 75 per cent black chocolate, lie-ins and the smell of freshly mown grass in my book. So I have trouble recognising the people she describes in I Hate Men as “violent, egotistical, lazy and cowardly”, and I’m a little worried by the notion that they should be phased out.

“Listen, eradicating men is not my aim,” assures Harmange – a demure, softly-spoken brunette in an off-the-shoulder t-shirt. “Ideally the book would help bring men back down to a normal position alongside the rest of us, and at the same time liberate women from the weight of that all-powerful patriarchy.”

A visceral loathing of men is both natural and logical, says Harmange in her introductory argument – in fact “the place they take in conversations, in public space, their words and actions as a group, make misandry easy.” The feminist activist then dedicates the first half of the book not so much to bringing men down with a bump, as pushing the whole species off a cliff. Hating men “is not the end of the road. On the contrary, it is the very beginning, you emancipate yourself first by recognising that you are p----- off (with men), and then by acknowledging that you have good reason to be.”

I have to raise a hand here, and ask the obvious question: can hate ever liberate anyone? After all, every zen-master in history remains convinced that love is a rather better option. “Yes, hate can,” nods Harmange, the Lille-born daughter of two college professors. “Because by distancing ourselves from the male gaze and male expectations women can be free.”

Although Harmange briefly touches on the love she feels for her husband, who “has read the book twice and really likes it,” she tells me (shortly before he brings her a cup of tea, unprompted), and the love she feels for her father, who has also read her work “and is open to seeing things from a different perspective,” women are better off without the opposite sex. “Statistically the more we distance ourselves from men, the more likely we are to live in good health and for a long time,” she explains.

Her activism flourished from “absorb[ing] the experiences of the women around me.” And it is the wider impact of women’s plight that Harmange returns to throughout the book: France has one of the highest rates of murders linked to domestic violence in Western Europe, with 149 women killed by their significant other in 2019 alone. The country also has woefully low prosecution figures in rape and sexual harassment cases.

“‘Seduction’ is considered a French way of life, and so the taboo is even stronger than elsewhere, and there’s an assumption that women should allow themselves to be harassed in the street,” she says.

It’s also true that as the world rose up to fight these assumptions in the wake of Me Too, France was the only country where 100 prominent French women artists and intellectuals – including Catherine Deneuve – fought back, writing an open letter in Le Monde that condemned the calling out of inappropriate male behaviour and a “puritanism in the name of a so-called greater good.”

And although Harmange tells me “it’s very tricky to criticise a woman when you’re a feminist, Deneuve doesn’t live through the same things as the average French woman does in the street or on the métro. She’s talking from her rich, famous, privileged position, which has no value for the rest of us.”

Equally empty, she says, is the post Me Too virtue signalling. “I mistrust any man who calls himself a feminist. It’s a term forged by and for women, and men should use other terms and tools to show their support for our battle.”

The feminist fight is not one we can fight together – Harmange is resolute on that. And it’s not up to us to show them the way: “We have been trying for so long to help men understand what we live through, so it’s up to them now to instigate their own action.” And no, we don’t need them as allies, “because it’s the sisterhood that is necessary to move forward.”

It’s no good pointing out my own experiences with a very unsisterly sisterhood – both at an all-girls school and with female bosses – or quoting Meryl Streep, who was pilloried last year for saying that “Women can be pretty f------- toxic.”

Harmange believes that “women have developed a way of socialising and a rivalry that’s about men. And when women become [bad] bosses, they have often absorbed male codes of behaviour in order to be taken seriously in a male world. But of course,” she concedes, “there is a personality aspect, in that just as there are men who are not nice human beings, there are also women who are not.”

For a moment, I feel defeated. Is there really nothing she likes about men, I manage eventually? Deliciously deep voices, protective impulses – or forearms? Male forearms are lovely. Harmange thinks about this. “I suppose they have a higher level of confidence than we do, and that’s great for them. What would be even better is if we could mix that confidence with our natural humility to reach a better and more equal level for both of us.”

Before I let Harmange get on with the important business of spreading hate, I find one thing we do agree on. If a man wrote a book entitled ‘I Hate Women’… “it would never be published,” she concedes. “It would be too politically charged.” Whereas her “ode to misandry”? “But misandry isn’t about violent repercussions against men – that’s the difference. There is no call to hatred or to violence in my book.”

Ralph Zurmély wouldn’t agree. What, out of interest, would she say to the government’s adviser for gender equality, if she had the chance? “I would ask him whether he didn’t have better things to do with his working day. But above all,” she says with a broad smile, “I would say ‘thank you’.”