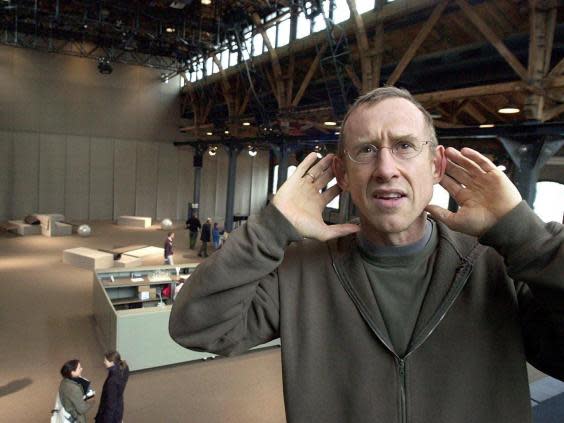

William Forsythe interview: 'I like being part of the big ballet conversation'

“Give me a little booty! Show off! Glissade, glissade, tombé, ballonné, piqué, yessssss!” William Forsythe calls out ballet steps, bouncing through them on sneakered feet.

A large group of dancers at Boston Ballet sway their hips and shoulders to the infectious rhythms, as they watch two principals whirl through a sequence that Forsythe has just choreographed – part of a new piece he is creating here for Full on Forsythe, an evening devoted to his work.

Forsythe turns happily to a few observers: “Isn’t ballet delightful?”

At 69, Forsythe has been finding ballet delightful since he first went to a class at 17. But he took an almost 20-year hiatus from what he describes as “working within the academy”.

Widely considered one of the most important choreographers working today, Forsythe is a New Yorker who made his career in Europe. First in Stuttgart, Germany, then for two decades as director of Frankfurt Ballet, he took the genre in new directions by both ignoring and exploring its conventions – taking positions out of classical alignment; testing limits of balance, extension and strength; inventing strategies to generate movement; adding text, film and innovative lighting.

Even before Frankfurt Ballet closed in 2004, Forsythe had headed into more theatrical and improvisational terrain, which he would continue to investigate with the Forsythe Company, a smaller ensemble founded in 2005. Two works created for the Paris Opera Ballet in 1999 were more or less his farewell to the extensions of balletic form that had put him on the map. Audiences craving more of the unblinking modernity that Forsythe had brought to classical dance had to content themselves with older works.

But Forsythe has come back to making ballet.

Since leaving the Forsythe Company in 2015 he has created two pieces (Blake Works 1, Playlist [Track 1, 2]) for ballet companies and one (A Quiet Evening) for a small group of his own longtime dancers – joyous, detailed riffs on ballet technique and tradition, danced to pop music, Rameau and in silence. (Quiet Evening will come to The Shed in New York in October.)

His new work for Boston Ballet, Playlist (EP), will be his first for a North American ballet company in almost 30 years. It shares a program with Blake Works 1 and Pas/Parts 2018, a revised version of one of the 1999 Paris pieces. (His last US commission, Herman Schmerman, created for New York City Ballet’s 1992 Diamond Project, was revived there this season and is currently being performed.)

Without the responsibilities of running a company, free to choose where he would like to work, and with time “to practise a lot” at his home in Vermont, Forsythe – who also has a growing presence in the art world – seems newly invigorated by the joy of working with ballet dancers.

“I knew I wanted to move back to strict ballet after the Forsythe Company ended,” he says in an interview after a long day of rehearsal here. “When you look at the great works of Bournonville, Petipa, Balanchine, you realise that the possibilities are endless. It is up to you to find the recombinations that turn the academy into a form of vital communication.”

In the early part of his career, as resident choreographer with the Stuttgart Ballet and then as director of the Frankfurt Ballet, Forsythe created ballets that established him as a groundbreaking and often divisive experimental artist in a field that is by definition a historical genre.

Forsythe’s pre-1999 work – like George Balanchine’s – asked why ballet couldn’t be as representative of our time as any work of contemporary art. He pushed Balanchine’s expansion of ballet vocabulary – the elongated extensions, the tensions of weight and balance, the stripped-down aesthetic – into even more extreme terrain. He played with conventions, abandoned ballet’s traditional gender roles, used electronic music (frequently by Dutch composer Thom Willems), designed his own innovative lighting and brought text and film into his work, often inspired by philosophical or theoretical writings and ideas.

Broadly speaking, European audiences adored it; American critics – with some exceptions – hated it. As a result, until 1998, when the Frankfurt Ballet first began to occasionally perform at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, dance audiences in the United States saw little of his work apart from a few early pieces that began to percolate into ballet companies.

But Mikko Nissinen, the artistic director of Boston Ballet, says he was not daunted by that history. “For me, he is the person who has moved the art form forward after Balanchine,” he says. “Our art form is in need of genius and here we have a profound, strong American voice. It baffles me that some people are blind to this.”

Fulfilling a long-held desire for his company, Nissinen entered into a five-year partnership with Forsythe in 2016; Boston Ballet will acquire at least one of his works each year.

If Forsythe’s earlier ballets were explorations of the outer limits of the genre, his post-2014 work seems to be digging ever deeper into its core, looking hard at ballet’s history to bring it into the future. In Blake Works 1, set to seven songs by James Blake, he mined the rich technical heritage of the Paris Opera Ballet dancers, incorporating combinations that have been passed down by generations of teachers, and emphasising the beaten footwork and refined arms that are French stylistic hallmarks. He has done something analogous in Playlist (EP), which begins with two sections created for English National Ballet and adds another four songs.

“I’m looking at all the interesting cross disseminations you get when you have a company made up of dancers from all over the world,” Forsythe says, noting that the Boston dancers come from Russia, South Korea, North America and Europe, all with different training. Playlist, he adds, quotes classroom combinations he remembered from teachers and from ballet classes seen while working in Paris, London and Boston.

The new work is also sprinkled with ballet history. “Paquita!” calls out a dancer, when Forsythe asks the group if they recognise a sequence he gave them. “It’s the ‘Paquita’ cha-cha now,” Forsythe laughs, referring to the 19th century ballet choreographed (in part) by Marius Petipa. “I keep watching the ballet on YouTube,” he says later. “The combinations, the complexities of the choreography, are just genius.”

But no matter how inspired by the past, or dedicated to ballet history, Forsythe’s physical style is distinctively and idiosyncratically personal: classical shapes, subtly transformed by angled hips and shoulders; academic form permeated by disco bounce; constantly shifting dynamics.

He is also not choreographing to music by Ludwig Minkus (Paquita, Don Quixote) or Tchaikovsky. With Blake Works 1 and Playlist (EP), he has turned to pop music, just as he did early in his career in works like Love Songs (1979) and Say Bye Bye (1980).

Playlist (EP) is an honest title. The work is set to six irresistible songs that were on the ever-expanding playlist on Forsythe’s phone: Peven Everett’s “Surely Shorty”, Lion Babe and Jax Jones’s “Impossible”, Abra’s “Vegas”, Khalid’s “Location”, Barry White’s “Sha La La Means I Love You” and Natalie Cole’s “This Will Be (An Everlasting Love).”

“This was the root of dancing for me,” Forsythe says. “My first dancing was in clubs and in musicals; I only engaged with ballet later.” Pop music, he adds, “has very clear structure, just like classical music; the nature of the syncopations and the underlying contrapuntal motors of the music allow the same kind of drive that Tchaikovsky, Prokofiev and Stravinsky brought to ballet music. It has a deep connection to dance that is entirely supportive to ballet.”

Nissinen says he was initially a little surprised by Forsythe’s musical choices. “Then I thought, why not?” he says. “I think it’s his reaction to being back in America. He wants to connect with people, bridge to broader audiences.

Working to music “you would listen to on a train”, says Chyrstyn Fentroy, a corps de ballet member (non-soloists), has allowed the dancers to loosen up and find “a swing” to their technique. “It forces you to rethink how you do a tendu or use your épaulement,” she says, referring to the complex relationships between head, shoulder and hips that are vital to ballet.

“I love the challenge of ballet,” Forsythe says one day as he constructs a complicated, overlapping ensemble sequence. “It’s like inventing a knot. You have the rope or cord, and you have to find the right relationships. It’s much harder than people think!”

Now and again, that is evident in the studio. Stymied one afternoon by a difficult passage in a pas de deux, Forsythe gets out his phone: “Siri, what’s the next step?” he asks. “You don’t appear to be heading anywhere,” she answers. Laughter all around.

Mostly, though, he seems to know exactly what he wants, reeling off strings of ballet steps as he demonstrates, the dancers picking up the movements with uncanny speed. (Once he went to consult photographs of M&M sweets, lined up in colour-coded formations that represented different stages of a section.)

Forsythe maintains he wasn’t aiming for anything groundbreaking or revolutionary. “I like being part of the big ballet conversation,” he says. “This is a celebration of everything ballet has brought to me in life. It’s just another way to love ballet – and there are so many ways.”

© The New York Times