The complex ethics of wildlife tourism – and how to do it with a clear conscience

A polar bear somersaulting metres above my head isn’t something I’d ever imagined. In the wild it would be impossible – I wouldn’t live to share the tale. But within the confines of Winnipeg’s Assiniboine Park Zoo in Canada, the apex predator can be seen daily swimming through a water tunnel in the Journey to Churchill exhibit.

The facility prides itself on providing a home for orphans and delinquent bears beyond rehabilitation, found roaming through the Canadian Arctic frontier town Churchill on the edge of the Hudson Bay. Yet despite good intentions, solid scientific arguments and attempts to keep the environment as natural as possible, it still felt uncomfortably wrong.

From zoos and aquariums to circus shows and petting farms, showcasing animals is increasingly perceived as exploitative rather than entertaining. Aristocratic menageries are – thankfully – an embarrassment belonging to the past.

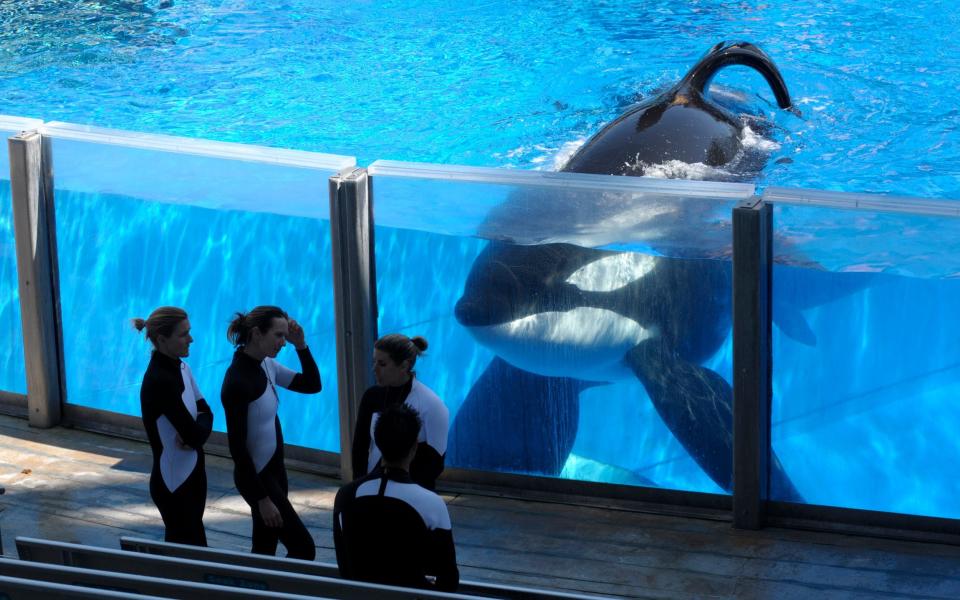

When troubled SeaWorld orca Tilikum dramatically carried the body of his trainer to a viewing window, a scandal which inspired the 2013 documentary Blackfish, public opinion of marine parks changed forever. 10 years later, the ripple effect continues.

Last week, package tour operator easyJet Holidays announced a new animal welfare policy, dropping any captivity attractions including zoos, marine parks and animal performances from its itineraries. Virgin Holidays already has similar guidelines in place.

Some culprits of animal cruelty are obvious: elephant rides in Thailand, swimming with dolphins in Dubai, petting canned lions, bred in captivity, in South Africa. But the ethics of wildlife tourism are far more nuanced. Drawing a line between what’s right and wrong is not an easy task.

Zoos and sanctuaries, for example, can play a vital role in conserving species and raising public awareness.

“Not all these experiences are 100 per cent negative,” explains Candice Buchan, Head of Rainbow Tours. “Sometimes the education on offer is valuable, and in some cases these organisations are doing important conservation or research work.”

Sir David Attenborough, a supporter of ZSL London Zoo, has a similar opinion.

“I justify zoos providing they are scientific, providing they are selective about what they keep and providing they keep them to the highest possible standards,” he has told reporters in the past.

Various zoological societies and institutions have played an important role in reviving species on the brink of extinction. Tanzania’s Grumeti Game Reserve, for example, has received black rhinos from San Diego Zoo and Port Lympne Safari Park in the UK. There’s an argument to suggest the northern white rhino, a species at the centre of a pioneering IVF scheme, would have disappeared years ago had a handful animals not been taken to zoos.

Some tour operators set the bar by distinguishing between activities that alter animal behaviour.

“Wildlife experiences should happen in the wild – on the animals’ terms,” insists Rob Perkins from Responsible Travel.

But even on icy plateaus and rolling unfenced plains, few encounters are truly natural. Travel brochures might trick you into thinking otherwise, but every animal on safari is conditioned to the sound of engines.

The best example of habituation is mountain gorillas in Rwanda and Uganda. While conservationists such as Dian Fossey were hesitant to accept tourism, it’s undoubtedly had a positive impact: since 1998, numbers of the species have risen from 620 to 1,063.

“Habituation of the great apes is essential for the species to thrive,” says Amos Wekesa, CEO of East African specialists Great Lakes Safaris. “Local communities need a reason to protect the species that are stealing their crops and stopping them from hunting in the forests.”

If not handled properly, however, tourism can be damaging. Over the years, I’ve witnessed some appalling behaviour on game drives in the Masai Mara as vehicles jostle for a position, disturbing cheetah hunts, chasing leopards and forcing several thousand migrating wildebeest to change course. A solution lies in community-owned conservancies, where numbers of visitors are carefully controlled and stakeholders can attach a financial benefit to protecting the wildlife on their doorstep.

“In an ideal world, we’d like to see national parks and their attendant wildlife conserved because it’s the right thing to do; because we believe that we should leave the planet in a better state than when we found it,” says Chris McIntyre, Managing Director for Expert Africa. “However, in the real world, we understand that these areas, and their wildlife, usually need to pay for themselves to be conserved.”

Camps like the Mara’s House In The Wild and Angama Amboseli do an excellent job of making communities central to their story. Asilia and Kicheche are other good safari companies to consider.

When choosing any type of wildlife holiday, Jarrad Kyte from Steppes Travel recommends three key considerations: community, conservation and code of conduct. Terry Moohan, Head of Africa and Indian Ocean at cazenove+loyd, also warns tourists to manage their expectations and accept what nature provides.

A window into an animal’s natural world is far more rewarding than a forced close encounter. But it’s important to remember that the concept of pure wilderness is a romantic fantasy when every inch of our planet has been impacted by humans. Any form of wildlife tourism is – at best - a compromise.

Five ethical ways to see animals

Musk oxen in Norway

Easily accessible by rail or road, Norway’s Dovrefjell National Park is the unlikely setting for an animal belonging to another era in time. Shaggy-haired musk oxen were introduced from Greenland between the 1930s and 1940s and have found a way to survive in the snowy valleys. Join a guided hike to view them on foot at a safe distance or watch from the comfort of the Viewpoint Snohetta, an architectural masterpiece of curved wood and glass.

Do it: Day hikes are from £46. Take the train from Oslo or Trondheim to Oppdal. Visit oppdalsafari.no

Red knots in Norfolk

Observing any species in large numbers is a thrilling experience. But mass migrations happen in more places than just Africa. From late summer to early winter, thousands of red knots populate mudflats at the Wash in Norfolk, viewable from hides in the RSPB Snettisham Reserve. A rising tide forces birds into the sky where they swirl in flocks, performing an aerial display known as the Snettisham Spectacular. The RSPB website has a list of the key dates when tides when this will happen.

Book it: Entrance to the reserve is free, although parking costs £3. Visit rspb.org.uk

Red kites in Scotland

Once Britain’s most common bird of prey, red kites were persecuted by gamekeepers and almost wiped out by the 1900s. Reintroduced to central Scotland, several pairs took up roost on the family owned Argaty Estate. In partnership with the RSPB and Scottish Natural Heritage, couple Lynn and Niall Bowser established the area’s only official feeding station, where visitors can get a close look at the graceful raptors from hides. The family has two guest cottages within their grounds.

Book it: Three nights are from £375 (sleeping up to six). Day visits from £7. Visit argatyredkites.co.uk

Whales in the Azores

Given the number of marine mammals in our nearby waters, there’s no need to visit aquariums. Sightings of sperm, blue, fin, sei and humpback whales – along with Risso’s and common dolphins – make the Azores Europe’s premier cetacean spotting destination. Assist researchers with photographing species and collecting data on whale watching trips between March and May when many of the migrating giants pass through.

Book it: Wildlife Worldwide can arrange a six-day trip from £1,595pp, including flights. Visit wildlifeworldwide.com

Gorillas in East Africa

The restoration of Rwanda’s Akagera National Park is a remarkable success story, due largely to the work of NGO African Parks. Learn about their anti-poaching measures and efforts to reduce human-wildlife conflict as part of a longer behind the scenes tailor-made tour of the country and neighbouring Uganda. Meet Batwa communities, once forcibly evicted from the forest, in Mgahinga Gorilla National Park, and trek gorillas in Bwindi Impenetrable Forest.

Book it: A 10-night trip costs from £7,365, including flights. Various departures. Visit rainbowtours.co.uk