Why I won’t be going vegan this January

The humble egg fills me with wonder. Hold it in your palm. Crack it. Scramble, fry, bake or poach it. Have it in cakes, in batter, in your hangover cure. Eggs are an everyday part of my diet, not just due to their simplicity but their nutritional weight. Rich in vitamin B2, B12 and D, selenium and iodine, folate and biotin. I could go on...

A vegan friend almost put me off them once by calling them a chicken period. For a couple of seconds I winced, and then I pulled myself together.

By that logic I’d end up like the fruitarian in Notting Hill, or the influencer Zhanna D’Art who tragically died in June last year after apparently living on a “fully fruit-based-low-fat diet” for the past five years.

Having dabbled with vegetarianism, I now occasionally eat fish and even rarely (and certainly rare) red meat, because as much as I want animals to have good lives, I too want a long, happy, healthy one too.

Vegan, though, I have never been. However, whether it is out of concern for animal welfare, the planet’s, or personal health, Veganuary is often the first point of experimentation with a more plant-based diet.

While upping your veg intake gets two big thumbs up from me, on a visit to my local East End cafe recently, I found that among the sandwiches available one was “zalmon”, one “facon” and one “cheeze”. I passed up all three and went and made some real, unprocessed, non-vegan food at home.

The nutrition gap

Two years ago, the podcaster Cara McGoogan decided to take part in Veganuary motivated by concerns about the environment and her health. After the first month she felt great and had even lost weight, but after two months, she says: “My nails started breaking and I missed a period.”

A vegan diet has been praised for its health benefits as it is typically higher in fibre and lower in cholesterol than an omnivorous diet. As a result, some studies find a vegan diet lowers the risk of heart disease and premature death, helps to manage type 2 diabetes and reduces the risk of cancer.

“A vegan diet can look very, very healthy,” says Dr Saliha Mahmood-Ahmed, a gastroenterologist, winner of MasterChef and author of The Kitchen Prescription. “It can mean you have reduced chances of chronic illness and it can mean a reduction in the risk of heart disease and diabetes, when done well. However, a vegan diet doesn’t necessarily have to be healthy.”

After her health deteriorated, McGoogan researched more fully the nutritional needs not met by eliminating meat and dairy, and started to take supplements. Today, she is no longer vegan and feels it would never have worked for her in the long term. “I always felt hungry and had to eat all the time.”

Of course, for every story like Cara’s there are plenty of people following a vegan diet who have experienced none of the side-effects she did. However, that it is a diet that should be embarked on with caveats is something most committed vegans wouldn’t deny.

“There are some key nutrients that can’t be obtained via a fully plant-based diet and it is important that these are supplemented correctly,” says Hannah Whittaker, a dietitian who specialises in milk-based allergies and plant-based pregnancy. Whittaker prefers to use the term plant-based, saying: “Veganism is a whole way of life. I think it’s very difficult to be a strict vegan.”

A recent global study suggested that the trend towards vegan diets is putting the health of pregnant women and babies at risk. Researchers found 90 per cent of expectant mothers in high-income countries, including the UK, were lacking key vitamins needed for healthy pregnancies.

They included vitamins B12, B6 and D, as well as folic acid and riboflavin which are key to the development of unborn babies in the womb. All are found “in abundance” in meat and dairy products, the scientists said.

In Whittaker’s experience, the demographic most likely to embark on a plant-based diet is women aged between 18-30. “This is also the age in which women may be planning pregnancy and nutritional intake is not only important during pregnancy but also to support conception,” says Whittaker, who herself follows a largely plant-based diet but eats fish once or twice a month from sustainable sources.

While Whittaker believes it is possible to supplement fully, she says: “If this demographic isn’t fully aware of their nutritional needs, it can have consequences for their future child’s development.”

Indeed, in 2016, the German Society for Nutrition went so far as to categorically state that – for children, pregnant or nursing women and adolescents – vegan diets are not recommended.

The UPF trap

The first mistake most vegan or plant-based converts make is to try to find direct swaps for the food products they are eliminating. The vegan processed food market has exploded in recent years. However, 2023 saw this market shrink.

Research from The Grocer suggested that the range of meat-free goods offered in supermarkets shrank by 10 per cent in the six months to March 2023 as firms cut back on product lines. However, there is still a huge range of meat alternatives on the market that can be tempting when you’re adapting to that meat-shaped hole on your plate.

“Rather than focusing on the nutrients they need, they go for alternatives to meat and dairy products that aren’t nutritionally the same,” says Whittaker. “However, these can be high in saturated fat, salt and sugars and can have poor nutritional quality.

“They’re usually pumped full of coconut oils and rapeseed oils and high in salt and lots of different emulsifiers to give you that mouthfeel to make it like meat. Rather than focusing on the nutrients they need, they go for alternatives to meat and dairy products that aren’t nutritionally the same.”

Generally, this means swapping in plant-based milk for cow’s milk, legumes and pulses for meat. But, says Whittaker: “Where are the micronutrients?”

Dr Mahmood-Ahmed agrees. “A lot of people go into the diet blind. The number of patients I meet with anaemia on a vegan diet who’ve never even been told about the potential of running into these deficiencies is slightly scary.”

For Dr Mahmood-Ahmed, that is a product of our wider lack of education within our food culture, not just specifically about what you need to be a healthy vegan. “From a young age, we get very little information about where our food comes from, how to grow it and how much you should have. There’s a general lack of understanding in the general population about how to feed ourselves nutritionally.”

The vegan deficit

Even if you aren’t a sucker for a Beyond Meat burger and know that an unprocessed plant-based diet is best, you might still be falling into a vitamin deficiency. It’s typical to feel good during the honeymoon period of going fully plant-based. “People tend to lose weight when they go on a plant-based diet because they cut out the meat and meat can be higher in saturated fat, because of the type of meat they were eating before, things like sausages and bacon,” says Whittaker.

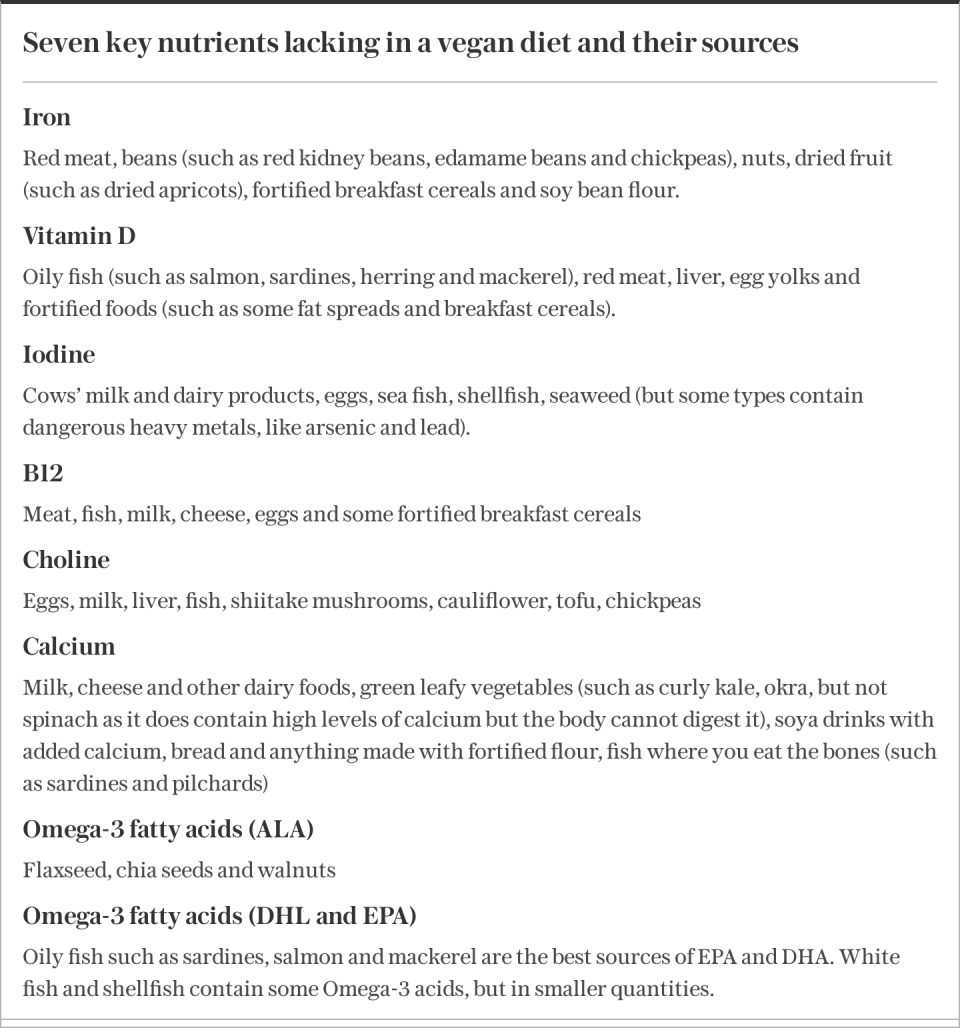

However after the initial boost, there can come a slump. The majority of conscientious plant-based eaters know they need to supplement B12, but they can be ignorant of the other vitamins and minerals lacking in a vegan diet.

The lesser-known nutrients most bio-available from animal products is the bread and butter of Whittaker’s work. “I have spoken at many conferences and had only one or two hands go up when I have asked about choline – and this is an audience of doctors, midwives and health visitors,” she says.

Choline

Choline is a nutrient your brain and nervous system need in order to regulate memory, mood, muscle control and other functions. “It’s important for brain development in children but also for adult mental health,” says Whittaker, and people who eat eggs tend to have almost double the choline levels of those who don’t.

“Eggs are a great source,” says Whittaker. “You get around 114mg via an egg. Requirement for the adult population is 450mg a day. And when you’re breastfeeding, the requirement goes up again.”

The liver makes a small amount of choline and while you can get some plant-based choline in your diet, Whittaker says: “It’s highly unlikely that you’re going to meet your choline requirement on a plant-based diet alone.”

The majority of multivitamins don’t contain choline, so Whittaker often works with clients to make sure they are getting it from elsewhere in their diet.

Iron

Another common deficiency is iron. In the UK, it is estimated that 3 per cent of men and 8 per cent of women have iron deficiency anaemia. Feeling generally more tired and being of a pale complexion can be a sign of iron deficiency. It’s the key reason I’ve reintroduced high-welfare red meat into my own diet once a month.

Leafy greens and pulses are also a good source of non-heme iron, but it’s not as easy to absorb. These foods also contain phytic acid that reduces the absorption of minerals. Several studies have found that coffee and other caffeinated drinks can reduce iron absorption. However, Vitamin C improves the absorption of non-heme iron.

Making sure that you are able to absorb the iron in your veg can be as simple as squeezing a little lemon juice on your spinach, or adding some peppers into your lentil curry.

Iodine

Another element lacking in plant-based diets is iodine. Iodine helps make thyroid hormones, which help keep cells and the metabolic rate healthy. “We need it for a healthy, functioning thyroid,” says Whittaker. “Iodine deficiency is the most common cause of goiter on the neck.”

If you do not have enough iodine in your diet, the thyroid gets larger to try to capture all the iodine it can, so it can make the right amount of thyroid hormone. Generally milk, dairy products and fish are the most bioavailable sources of iodine. Iodine can also be found in plant foods, such as cereals and grains, but the levels vary depending on the amount of iodine in the soil where the plants are grown.

“Seaweed has a high concentration of iodine, but it contains variable amounts and intake can lead to excessive iodine,” adds Whittaker.

Omega-3

This beneficial fatty acid comes in three forms. ALA is found in plants such as flaxseed, soy and walnut oil. DHA and EPA are present in fish, fish oils, and krill oils, as a result of fish consuming phytoplankton rich algae.

They are important for foetal development, including neuronal, retinal, and immune function. EPA and DHA may affect many aspects of cardiovascular function.

However, Whittaker points out: “Diet surveys show that even people who eat animal products don’t get enough DHA because they don’t eat fish.”

Vitamin B12

This is the one most vegans know they need to supplement. Vitamin B12 (cobalamin) is crucial for nerve tissue, brain function and red blood cells. Sources include meat, eggs, and some yeast products (nutritional yeast is a good source in a vegan diet). People whose diet is low on B12 may need supplements. Signs of a deficiency include headaches and fatigue.

“Deficiency can cause anaemia and in extreme cases it can cause neurological difficulties in people,” says Whittaker. “It becomes quite important if you are pregnant or breastfeeding and you’re on a vegan diet because your demand for B12 increases in those periods.”

In India, a country in which non-meat eating is entwined with religious culture, B12 deficiency is endemic. Reports suggest that at least 47 per cent of the Indian population suffers from low B12 levels in the body and only 26 per cent of the population may be vitamin B12 sufficient.

“Making sure you’re getting it from alternative sources is really important if you’re not going to get the readily available B12 you get from meat and dairy,” says Whittaker.

Other common deficiencies among vegans include D3, selenium, folate and calcium.

We all rely upon skin exposure to the sun to make Vitamin D, however during winter, omnivores living in the UK have nearly 40 per cent more vitamin D3 in their blood than vegans.

A lot of attention is given to protein but this actually is the least worrying deficiency. “You can get plenty of protein on a plant-based diet,” says Dr Mahmood Ahmed.

The long-term impact

Relying on supplements rather than food for your vitamins and minerals is a long way from the way I aspire to live my life. However, for those who care deeply about not eating meat, it’s a trade-off considered worth making. And of course, there are plenty of skilled, exciting and delicious vegan cooks out there.

Despite my own distaste about intensive agriculture (Of the 1.12 billion chickens killed for meat annually in the UK, around 95 per cent are factory farmed) cutting out animal products entirely is not a risk I’m willing to take. Eating less but better has become my ethical standpoint.

Not everyone on a vegan diet will need to supplement, and Dr Mahmood Ahmed worries that lots of people may be wasting money on expensive vitamin pills they don’t even need. “This whole market of functional foods that exists at the moment, a lot of it is very very faddy,” she says. “We have to be very wary about what we put inside us, how much it costs and whether it’s actually making a difference and what the evidence behind it is.”

While I have some sympathy with the ethical rationale behind a vegan diet, it is the long-term consequences to my health that I fear. Scientific studies struggle to make a fair comparison between vegans and meat-eaters as the former tend to have an all-round healthier lifestyle; such as not drinking or smoking. However, some studies suggest that a vegan diet can have a negative impact on human health.

A recent study involving 48,000 people over 18 years compared the health of meat-eaters, pescatarians – who eat fish and dairy, but not meat – and vegetarians, including some vegans. They found that people who eat vegan and vegetarian diets have a lower risk of heart disease, but a higher risk of stroke, possibly partly due to a lack of B12.

There is also some evidence to support the theory that the risk of fracture for vegans is higher than for meat eaters, fish eaters and vegetarians, due to their lower intake of calcium. The 2020 study was conducted by the University of Oxford and published in the journal BMC Medicine.

However, a 2023 study published in scientific journal Osteoporosis International, found that older adults, especially women, who follow a plant-based diet could be at lower risk for osteoporosis. So the case is far from clear.

Brain health is the area that causes me the most concern. The amount of B12 in a person’s blood later in life has been directly correlated with their IQ. One study found that the brains of elderly people with lower B12 were six times more likely to be shrinking.

Iron is another element crucial to brain health. A 2007 study found that giving young women iron supplements led to significant intellectual gains. In those whose blood iron levels increased over the course of the study, their performance on a cognitive test improved between five and sevenfold, while participants whose haemoglobin levels went up experienced gains in their processing speed.

While eating a steak is unlikely to make me Albert Einstein, making the most of what brain cells I have seems sensible.

Going half-the-hog

After experiencing symptoms of fatigue, increased appetite, hair loss, weight loss and inflamed skin, Camilla Mason (not her real name) says that she now eats “like a Tudor earl”.

Eating venison, a non-farmed meat that is available in abundance, is her way of still being aware of ethical issues around intensive farming practices. Importantly it also acknowledges that she needs more protein and fat than a vegan diet provided for her.

“I wouldn’t eat anything if I thought the quality or origins were dubious. Most of my meals are still vegetarian. I eat a lot of fish and eggs. From my experience of going vegan, I’m now much more clued up on protein and iron needs for my body, so that’s what I try and prioritise.”

Despite her experience of being vegan, Mason still thinks it’s possible to have a vegan diet without the health issues she encountered: “I think I was doing it wrong, basically. If I had been more aware of nutritional needs and had taken supplements accordingly, I think I could have managed it much better. However, I feel happier and more relaxed now with my current approach.”

Dr Mahmood-Ahmed agrees that it is possible to be vegan and healthy. “If you’re eating a vegan diet where you get 30 plant-based foods a week and you cook for yourself it is highly unlikely you’ll run into any nutritional deficiency-related issues. The quality of a vegan diet is really critical here.”

Even still, a veg-centric approach is how Dr Mahmood-Ahmed prefers to describe her own diet. Having grown up in a Muslim household, where meat is central to family and religious life, she says: “We ate meat every day pretty much.”

Reaching the point where she has a few vegetarian or plant-based days a week has been a journey. “My tastes have just gradually changed over time. Part of it was education. Part of it was becoming my own person and deciding what I enjoy more.”

That we live in a meat eating culture in the UK has to be acknowledged, but says Dr Mahmood-Ahmed: “It shouldn’t make us think that you have to eat a lot of it.

“If meat eaters could be just a little bit more vegan or vegetarian sometimes, I think they’d be doing their health a lot of good. And their pocket, because meat is very expensive. Speaking as a mother and someone who runs a household budget, you can buy a lot of legumes and pulses for a lot less and make it go a lot further.”

She and her family have regular “Veg Wednesdays”. She advocates small switches such as having a vegetable curry one night instead of your usual chicken. “It might feel relatively insignificant but if you add those days up over the course of a week or month you’ve actually made a significant, positive dietary change.”

It’s a nuanced approach that doesn’t fit with the all or nothing messaging of Veganuary.

A diet you can sustain

Whatever your motivation, Dr Mahmood-Ahmed advises against treating veganism like a fad diet that you do for a little while and then give up.

“We know that restrictive diets don’t work. Whether it’s Keto or Atkins, the science has shown that people will lose weight initially and then they put it back on because the restrictive changes were too difficult to maintain long-term. If you treat veganism in the same way that’s exactly what’s going to happen to you.”

Her advice is to take the messages that are positive from a vegan diet, such as eating a wider range of plant based foods that are crucial for gut health.

“One key thing that’s really important that’s going to be better on a vegan diet is fibre. Fibre is so important for bowel health, appetite regulation and a supported immune system,” she says. “I would hate people to be vegan for a month for the sake of it and not take some of the really great things about a vegan diet into their life in the long term.”

Meanwhile for Whittaker, it’s important that whatever you decide is best for you, your choice is made free from judgement. “You should never be criticised for your dietary choices. If you want a glass of milk, or some fish, you go and have some.”

She cites the example of the singer Jessie J who switched back to eating meat when she was pregnant and was chastised on the internet. “Whether your dietary decisions are for animal welfare or your human health, it’s your personal choice.”