Why the Metropolitan Line embodies the brilliance of Britain

Everything about the Metropolitan line is richly English. It personifies the British trick of creating new things and making them seem old: the world’s original underground train now layered with conservative nostalgia; the first underground line to be built but the last to be nationalised; the railway that began in a smog-heavy Victorian city and went on to conjure up for millions the dream of “fresh air, sunlight, roomy houses, green lawns and social advantages” in the rolling hills of Middlesex, Hertfordshire and Buckinghamshire.

Its very name sings of the city, but most of its 41 miles are suburban or rural. The urban Metropolitan created the suburban Metro-land as its 4-4-0 steam tank engines gave way to “the red electric train” and the stuccoed ranks of Paddington Italianate terraced houses evolved to the bargeboards, pebbledash and mock timber frames of Metro-land’s “Stockbroker Tudor” and “Bypass Variegated”. When you ride the Metropolitan from Farringdon to Chesham, you are not just passing through lost Middlesex but travelling through time. It is no wonder, really, that it ranked as the best Underground line in a recent study by The Telegraph.

The paradox began in 1860 with a mess on the Euston Road. The Metropolitan’s progenitor was an elderly solicitor, Charles Pearson, born in the 18th century, who first proposed the idea in 1845. Without Pearson’s obsessive persistence, penning pamphlets, proposing schemes and arranging finance, the Metropolitan Railway, as it was then called, would never have been created. It ran from Paddington to Farringdon beneath London’s first bypass (the 18th-century “New Road”, now the A501) and down the valley of the lost river Fleet.

Its construction was an awful nuisance. The Victorian railway chronicler Frederick Smeeton Williams described the horrors facing a nearby homeowner: “An infinite chaos of timber, shaft holes, ascending and descending chains and iron buckets… workmen shoring up his family abode with huge timbers to make it safer… he can hardly get out to business or home to supper without slipping.”

The Metropolitan was built fast, completed in less than two years and opened on Saturday January 10 1863. It was bold, brash and ahead of its time. Paris had no Metro till 1900; New York none until 1904. Conditions were initially appalling, with tunnels filled, according to one traveller, with “sulphuric fumes”.

However, in the first of its many contradictions, the Metropolitan was also an immediate and runaway success: 30,000 people used the line on its first day and 11.8 million in its first year. Profits were spectacular: £102,000 in year one with a generous dividend of 6.25 per cent. The future was popular, and it paid.

Directors invested those profits well. They grew and electrified the network with remarkable speed. Initially, the line expanded east to Moorgate and west to Hammersmith (on what are now the Hammersmith & City and District Lines) and then, most emblematically, through construction and purchase north-west to Swiss Cottage, Harrow, Pinner, Rickmansworth, Chorleywood, Aylesbury and Verney Junction, 50 miles from distant Baker Street.

What next? The train had run beyond its commuter market. How to continue to pay dividends? Starting in Pinner in 1900, the Metropolitan started building homes on surplus land: laying out streets, granting building leases and selling ground rents. If there were no commuters then they would create them. In doing so they helped forge 20th-century Britain, the home-owning democracy of respectable suburban living.

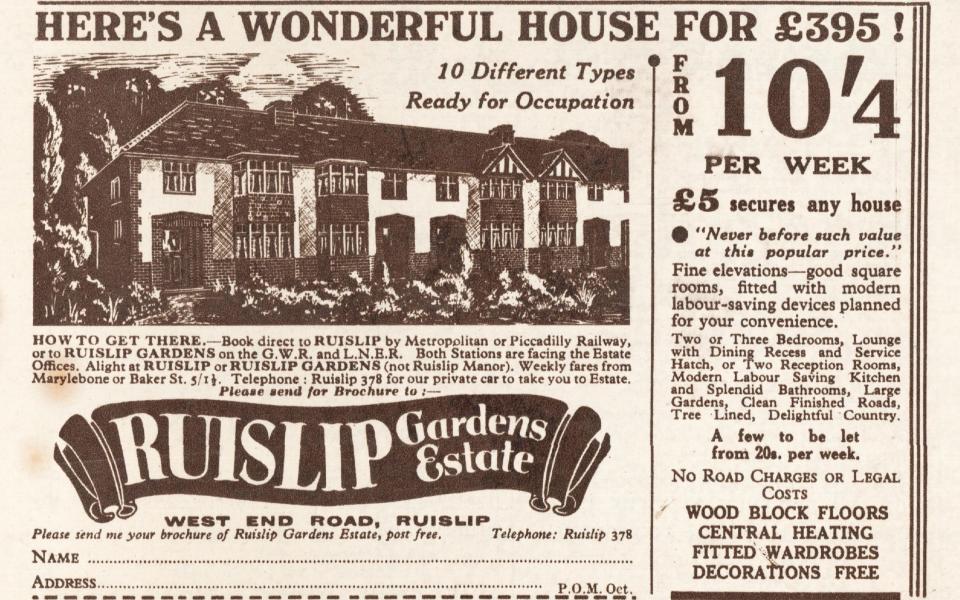

Early brochures extolled the virtues of home ownership as opposed to the “uneasy feeling” of the tenant, the norm for most, even middle-class Victorian families. The Metropolitan’s “lush brochures” gave this suburban “home-is-my-castle” dream a name: “Metro-land”.

Metro-land’s bard was John Betjeman. His love, initially ironic then sincere, for the neighbourhoods the Metropolitan created, the social advancement they encouraged, and the suburban gentility they permitted, permeates his poetry and prose.

Of Betjeman’s many gifts to England’s literary landscape, from the Cornish coast to the pines of Aldershot, none is greater than Metro-land, the marketing slogan of a nameless 1915 copywriter, which he imbued with the yearning aspirations of the commuting clerk, shopping housewife or “office gal” returning home to Moor Park or Ruislip Gardens.

Betjeman the child undertook “expeditions by North London trains / To dim forgotten stations, wooden shacks / On oil-lit flimsy platforms among fields”. By the time the 67-year-old Betjeman made his voyage along the Metropolitan line for his elegiac 1973 film Metro-land, the fields were gone but he was as enamoured of the “Bucks homesteads” as its inhabitants.

The Metropolitan was nationalised, against its wishes, in 1933. The green belt prevented the new London Passenger Transport Board from developing land. And thus, unable to create commuters, it shrank. It has retreated nearly 30 miles from Verney Junction to Chesham.

We may love the Metropolitan, the line to the Chilterns, the only Tube with fast and all-stations services, whose livery recalls, just, its early red carriages, but it is only a portion of what it once was.