Why Hollywood stars have started smoking again

Oscar Wilde once wrote in The Picture of Dorian Gray that “A cigarette is the perfect type of a perfect pleasure. It is exquisite, and it leaves one unsatisfied. What more can one want?” For many years, cinema took the Wildean image of the cigarette as the Platonic idea of sophistication and developed it even further.

Who can forget Sean Connery’s introduction as 007 in Dr No, lighting a Craven A cigarette as he says the words “Bond…James Bond” for the first time on screen, or Humphrey Bogart disconsolately but stylishly smoking in Casablanca as he mourns his lost love Ilse, saying “Of all the gin joints, in all the towns, in all the world, she walks into mine.”

Smoking on screen historically denoted sexiness, class and cool. This was the case when Sharon Stone lit up a cigarette in an interrogation room in Basic Instinct, and sneered at the detectives interrogating her “What are you going to do? Charge me with smoking?” Some of the hippest films from the Nineties, from Pulp Fiction to Fight Club, featured their main characters smoking, and they immediately became part of the zeitgeist; it is not for nothing that Uma Thurman’s character on the poster of Pulp Fiction looks out defiantly, cigarette clutched in her hand with poise and defiance.

It was hard, coming of age in the Nineties, not to be impressed by it all, even as we were surrounded by health warnings; by the time I was at university, practically everyone I knew smoked. The only reason I refrained was because I was frankly rubbish at it, although I still had a few spluttering experiments, clutching my Marlboro lights as if they would connote instant cool upon me if I mastered the art of inhaling them.

Two decades later, the world is a very different place. The indoor smoking ban of 2007 immediately made bars, pubs and restaurants considerably less welcoming to smokers, and a combination of increasingly punitive tax rises for tobacco and a growing awareness of the apparently endless illnesses that a heavy smoking habit can lead to has meant that it is now almost a rarity to see people with a cigarette in their hands, although its less stylish replacement, vaping, has become all but ubiquitous.

Last year, the government, in what they called “the biggest public health intervention in a generation”, announced that they would raise the legal age for smoking year by year with the intention of eventually making it impossible for anyone legally to buy tobacco. The aim is that, by 2030, Britain will be smoke-free, with fewer than five per cent of adults smoking; currently there are still six million smokers in Great Britain, whose habit means that the tobacco industry paid £10 billion in taxes in 2022.

And the United States has become similarly anti-smoking, too; although the government has never attempted to introduce any blanket ban on tobacco, smoking rates have virtually halved over the past two decades, from 20.9 per cent of adults being smokers in 2005 to 11.5 per cent in 2021, thanks to many states and cities – from New York to California – making it all but impossible to smoke in any enclosed public area.

This concern for health – some would call it censoriousness or meddling – has extended to cinema, too. The last James Bond to smoke was Pierce Brosnan, in his ignominious swansong Die Another Day. And after a brief period in which on-screen smoking in mainstream cinema was the exclusive preserve of the villainous and the doomed, it seemed to disappear almost entirely.

The highest grossing films of the past couple of decades – the Avengers, Star Wars, Jurassic Worlds and the like – are cigarette-free zones, and it would be all but unthinkable for their stars to be seen smoking in public. When Iron Man himself, Robert Downey Jr, confessed in 2010 that he had taken up cigarettes once again, it seemed like a genuinely subversive admission (and this from a man whose substance abuse landed him in prison); a decade later, it was made clear that he had ditched the cancer sticks in favour of diet, exercise and meditation. In 2015 Disney banned smoking in films entirely, and five years later censored scenes of Goofy lighting up from its Dinsey+ streaming service.

All the same, after years of cinematic abstinence, that smoking has once again began to reappear in mainstream film. The new Anne Hathaway film Eileen, starring Hathaway as the enigmatic prison psychiatrist Rebecca Saint John, features the actress unapologetically smoking on screen, something that the famously health-conscious star says marked a considerable change of pace for her.

“To play anybody that’s a bit heightened, especially when you’re someone who, shall we say, I’ve become familiar to audiences, to know that you’re shaking up what maybe they’ve come to expect from you – from the way you sound to the way you walk to the colour of your hair to the fact that you smoke,” she said recently. “I had a bit of fear about whether or not the audience would lean in with me in this performance.” The excellent reviews she has received suggest that they have.

And there was a similar sense of transgression in Emerald Fennell’s much talked-about new black comic thriller Saltburn, in which Alison Oliver’s character Venetia Catton, the aristocratic daughter of the owners of the eponymous mansion, is showing rebelliously smoking at the dining table; this will result (spoiler alert!) in her being punished twice over, first in her apparent death from suicide, and secondly in the revelation that she has been coerced into committing the act by Barry Keoghan’s devilish social climber Oliver Quick.

It may seem like a high price to pay for one too many cigarettes at dinner, but nonetheless Venetia is portrayed as a glamorous, if disturbed, character. As with so much else in Saltburn, the transgression and seductiveness go hand in hand.

Help, I saw SALTBURN and can’t stop smoking my cigarettes in a sensual and cinematic fashion pic.twitter.com/mQF1p0oEXw

— DeVaughn Taylor (@_daddydisco) November 25, 2023

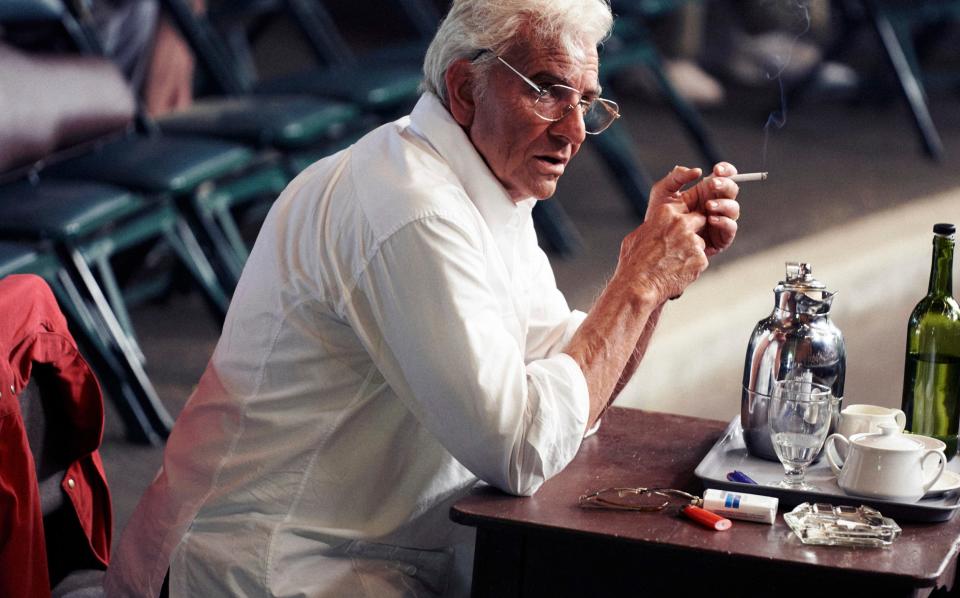

In period-set pictures, of course, there is far greater licence. While few films have gone as far as Mad Men, in which the characters (even pregnant women) were forever alternating between cigarettes and martinis, everything from Bradley Cooper’s Netflix film Maestro to Baz Lurhrmann’s Elvis shows their protagonists smoking. In 2019, Netflix announced that “We recognise that smoking is harmful and when portrayed positively on screen can adversely influence young people”, it is hard not to believe that filmmakers are tiring of the new spirit of censoriousness. Are we looking back to a golden age of glamour and excitement on screen, where the eclectic likes of Grease, The Graduate and The Good, The Bad and the Ugly all managed to make smoking seem iconic and exciting?

Variety estimated that, of last year’s Academy Award-nominated pictures, nine out of 10 of those up for Best Picture featured cigarettes or tobacco in some capacity, including the mega-grossing Top Gun: Maverick. Smoking is back in vogue, it would seem.

For some, the appeal is obvious. As the lifestyle and cultural journalist Kara Kennedy, who has written about her love of the activity, told me: “I’m an unrepentant smoker, because I don’t see anything that I need to be repentant about. I enjoy it because it’s one of the more civilised vices that you can pursue; it’s stylish, sociable and fun. Plus, it was good enough for some of the greatest actors of all time, and that’s set the tone for me ever since.”

And Simon Clark the (notably non-smoking) director of the smoker’s lobby group Forest (Freedom Organisation for the Right to Enjoy Smoking Tobacco) commented that “if directors of more adult orientated movies are pushing back against attempts to censor their work by denying them the creative freedom to portray smoking on screen, I would welcome it. Smoking in films should never be gratuitous, but if it’s character or plot driven, and reflects the real world, what’s the problem?”

Yet others see it in more nuanced terms. The film scholar Lucy Bolton is quick to acknowledge the appeal of stars with cigarettes on screen. “I think of Bette Davis and Ava Gardener smoking and it being part of their glamour but then it is also a major part of Sean Young’s image in Blade Runner and Michelle Pfeiffer’s in The Fabulous Baker Boys… From James Dean to Johnny Depp, Lauren Bacall to Lily Depp, if it looks alluring and cool, it will have an effect on impressionable audiences.”

Bolton puts the rise in contemporary on-screen cigarette smoking down to “rebellion, perhaps – libertarian rebellion – and people refusing to be told what to do”, even as she observes that “there is vaping now, and that looks much less subversive”. Should the likes of Timothée Chalamet and Naomi Ackie be publicly associated with smoking, she suggests, it would raise the activity’s popularity greatly. “They are young, cool actors who have big personalities and seem like fun. They are stylish, and that is the main draw.”

Clark disagrees: “Most people are clever enough to distinguish between an actor and the role they are playing on screen, so talk of ‘impressionable audiences’ is rather patronising,” he says. “And if the major star is a smoker in real life, it has nothing to do with anyone else. They’re actors working in what I imagine can be very stressful industry. They didn’t ask to be role models, nor should they be, so leave them alone!”

But even as she recognises the potential appeal of smoking, Bolton herself eschews it: “With a father who died from heart disease, after six heart attacks, and a triple bypass – all severely affected by smoking – I have never touched the stuff and never will.” And she believes that, even if cigarettes on cinema are having something of a comeback, their day is done. “Its heyday is passed – but it will always retain certain meanings, positive and negative, especially of rebellion.”

“Smoking will never be history,” says Clark, “but unless we invent a completely ‘safe’ cigarette I can’t imagine it will ever return to its previous popularity. There are two reasons for this. One, there are too many restrictions on the sale and consumption of combustible tobacco, most of which are unlikely to be reversed. Two, we know so much more about the health risks associated with smoking than we did 50 or 60 years ago, and that has obviously influenced recent generations not to start smoking. I can’t see that changing.”

There are many who are implacably anti-smoking, too, such as Hazel Cheeseman, Deputy Chief Executive of the group ASH (Action on Smoking and Health.) Cheeseman suggested that “Cinema is a reflection of social norms and expectations. As smoking has changed in the public imagination so its depiction in film has changed to reflect this.”

In her estimation, this can be pernicious. As she says: “Just having more smoking related imagery is a problem. Teenagers who see smoking related images in films are more likely to try smoking and the nature of that imagery, whether positive or negative, doesn’t seem to change that effect.” For Cheeseman, the consequences are obvious and inarguable. “It is highly addictive, kills two in three long term smokers and costs society around £49 billion a year. The only people in society who benefit from tobacco are the big tobacco companies.”

This is obviously true. Smoking is poisonous, health-limiting and expensive. But it’s also the iconography of Audrey Hepburn in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, Renee Zellweger in Bridget Jones’s Diary and James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause. As long as cinema exists, it is likely that cigarettes will continue to make appearances on screen, even as health professionals and studios alike fulminate against it. Perhaps they should bear another maxim of Wilde’s in mind as they do so: “Wickedness is a myth invented by good people to account for the curious attractiveness of others.”