Why is Friday the 13th unlucky? The cultural origins of an enduring superstition

When it comes to bad luck, there are few superstitions as pervasive in Western culture as that of Friday the 13th. Like crossing paths with a black cat and breaking a mirror, the notion of a day that can bring misfortune is deeply embedded — even if believers can’t quite explain why.

There’s even a name to describe the irrational dread of the date: paraskevidekatriaphobia — a specialized form of triskaidekaphobia, a fear of the number 13.

While Friday the 13th may feel like a rare phenomenon, our Gregorian calendar means that the 13th of any month is slightly more likely to fall on a Friday than any other day of the week. It is not, however, a universal superstition: In Greece and Spanish-speaking countries, it is Tuesday the 13th that is considered a day of bad luck, while in Italy, it is Friday the 17th that is met with fear.

This month, however, there is only one in the calendar: Friday, the 13th of September.

The makings of a superstition

Like many superstitions that have evolved over time and across cultures, it is difficult to pinpoint the precise origins of Friday 13th. What we do know, though, is that both Friday and the number 13 have been regarded as unlucky in certain cultures throughout history. In his book “Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things,” Charles Panati traces the concept of the cursed back to Norse mythology, when Loki, the god of mischief, gate-crashed a banquet in Valhalla, bringing the number of gods in attendance to 13. Deceived by Loki, the blind god Hodr was tricked into shooting his brother Balder, the god of light, joy and goodness, with a mistletoe-tipped arrow, killing him instantly.

From Scandinavia, Panati explains, the superstition then spread south throughout Europe, becoming well established along the Mediterranean by the start of the Christian era. It was here that the unsettling power of the numerals was cemented through the story of the Last Supper, which was attended by Jesus Christ and his disciples on Maundy Thursday. The 13th and most infamous guest to arrive, Judas Iscariot, was the disciple who betrayed Jesus, leading to his crucifixion on Good Friday.

In Biblical tradition, the concept of unlucky Fridays, stretches back even further than the crucifixion: Friday is said to be the day that Adam and Eve ate the forbidden fruit from the Tree of Knowledge; the day Cain murdered his brother, Abel; the day the Temple of Solomon was toppled; and the day Noah’s ark set sail in the Great Flood.

It wasn’t until the 19th century, however, that Friday 13th became synonymous with misfortune: As Steve Roud explains in “The Penguin Guide to the Superstitions of Britain and Ireland,” the combination of Friday and the number 13 is a Victorian invention. In 1907, the publication of Thomas W. Lawson’s popular novel “Friday, the Thirteenth” captured the imagination with its tale of an unscrupulous broker who took advantage of the superstitions around the date to deliberately crash the stock market.

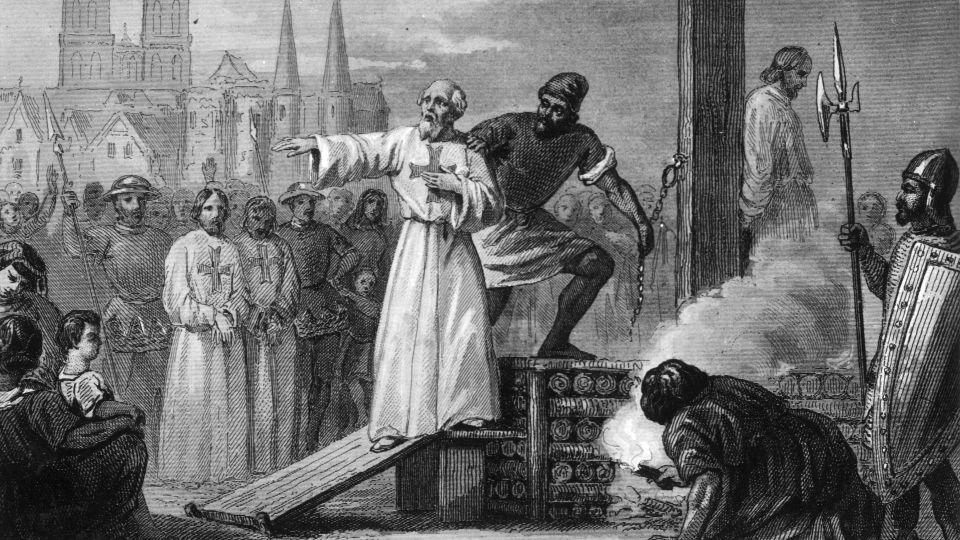

Fast forward to the 1980s, and a hockey-masked killer by the name of Jason Voorhees in the slasher flick franchise “Friday the 13th” ensured notoriety. Then came Dan Brown’s 2003 novel “The Da Vinci Code,” which helped popularize the incorrect claim that the superstition originated with the arrests of hundreds of members of the Knights Templar on Friday, October 13, 1307.

An alternative history

Given the mass of doom-laden lore, you’d be forgiven for thinking that Friday 13th is indeed ominous. If we dig deeper, though, we also find evidence that both Fridays and the number 13 have long been regarded as a harbinger of good fortune. In pagan times, for instance, Friday was believed to have a unique association with the divine feminine. The first clue can actually be found in the weekday name Friday, which is derived from Old English and means “day of Frigg.” Both Queen of Asgard and a powerful sky goddess in Norse mythology, Frigg (also known as Frigga) was associated with love, marriage and motherhood.

Frigg gave protection to homes and families, maintained social order, and could weave fate as she did the clouds. She also possessed the art of prophecy, and could bestow or remove fertility. On the other hand, Freyja, the goddess of love, fertility and war with whom Frigg was often conflated, was endowed with the power to perform magic, predict the future, and determine who would die in battles, and was said to ride a chariot pulled by two black cats. These goddesses were worshiped widely across Europe and, because of these associations, Friday was considered a lucky day for marriage by Norse and Teutonic people.

The number 13, meanwhile, has long been regarded as a portentous number by pre-Christian and goddess-worshipping cultures for its link to the number of lunar and menstrual cycles that occur in a calendar year. Fertility was prized in pagan times, and artwork would often draw connections to menstruation, fertility and the phases of the moon.

Take the Venus of Laussel, an approximately 25,000-year-old limestone carving depicting a voluptuous female figure cradling her pregnant stomach with one hand, and holding a crescent-shaped horn bearing 13 notches in the other. Many scholars believe the figurine may have represented a goddess of fertility in a ritual or ceremony, while the 13 lines are typically read as a reference to the lunar or menstrual cycle, both of which symbolize feminine power.

Rewriting a reputation

As Christianity gained momentum in the Middle Ages, however, paganism stood at odds with the new patriarchal faith. Not only did its leaders take objection to the worship of multiple gods and goddesses, but the celebration of Friday, the number 13, and the goddesses who invoked love, sex, fertility, magic and pleasure were deemed unholy.

So revered were these deities, though, that making people relinquish them proved a real challenge. But Christian authorities persisted with their campaign, branding both the deities and the women who worshiped them witches.

“When Norse and Germanic tribes converted to Christianity, Frigga was banished in shame to a mountaintop and labeled a witch,” Panati writes. “It was believed that every Friday, the spiteful goddess convened a meeting with eleven other witches, plus the devil — a gathering of thirteen — and plotted ill turns of fate for the coming week.”

These days, of course, Friday the 13th still haunts the Western imagination. But with conversations around the role misogyny has played in silencing powerful women throughout history now in the mainstream, perhaps the narrative of this unlucky date and the female deities associated with it might soon be rewritten.

The tide may have already started to turn: Take Taylor Swift, who considers 13 her lucky number and, early in her career, often performed with the number written on her hand.

“I was born on the 13th. I turned 13 on Friday the 13th. My first album went gold in 13 weeks. My first No. 1 one song had a 13-second intro,” she told MTV in 2009. “Every time I’ve won an award I’ve been seated in either the 13th seat, the 13th row, the 13th section or row M, which is the 13th letter. Basically, whenever a 13 comes up in my life, it’s a good thing.”

With more endorsements like this, fortune, rather than fear, might well become the legacy of Friday the 13th.

This article was originally published in 2021.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com