Why did I cry when I was approved for $271 of food stamps this month?

The other day, I got yet another job offer to “train AI”. The company had the audacity to list $15 an hour as a “perk” of the job.

I’ve spent much of my 25-year writing career as a freelancer. I was always excited to scoop a story for a major publication, but I couldn’t have survived without the bread-and-butter jobs: web copy, corporate blogging and product descriptions.

Now I can’t survive. I’ve made $3,000 this year, which is only 40% of what the US government considers a poverty level income. I’m living off my credit card while crafting an endless flurry of cover letters as my career prospects grow ever more depressing.

Fifteen dollars an hour to train AI to steal my livelihood? That was the last straw. I lost hope and did something I’ve stupidly avoided my whole life. I applied for government assistance.

If you look at the trajectory of my life, the real question is why I didn’t do it a lot sooner.

I couldn’t shake my memories. My dad pulling food stamps out of his wallet under the disapproving eyes of a cashier

Ironically, I got my first big break because I was poor. In the crash of 2008, I lost a lucrative writing contract the same week my husband was laid off. When his unemployment ran out, we moved back to my childhood home in rural Oregon and joined the 15% of Americans who could be considered “food insecure”. I was blogging about harvesting nettles for dinner when an editor at Salon invited me to write a weekly column, Scavenger, about cooking on a budget.

I was embarrassed to publicly admit we were poor, and $75 for a 1,700-word column wasn’t going to help much. But I thought the byline might get me somewhere. I made the gamble to put aside my pride, at least in one regard.

Unfortunately, people are assholes. Every week, hundreds of outraged commenters scrutinized my choices and asked questions like “Why didn’t I get a job?” Answer: the economy sucks everywhere, rural areas are much worse, and this was a job, and one I hoped would lead to better pay. (Furthermore, I was also doing yard work for $9 an hour.)

Another question was harder to answer: why wasn’t I on food stamps?

Why, indeed. I knew that I wasn’t alone in my struggle to put food on the table. When it comes to food, Oregon is the fifth-most expensive state in the US. The latest government data shows that one in six Oregonians receives Snap benefits, meaning they get financial assistance that can be spent on food only. (Nationwide, one in eight people receive what we colloquially refer to as “food stamps.”)

I was raised to believe it’s OK to accept assistance in times of need, and I knew what a difference it could make. My childhood would have been even bleaker if we hadn’t received government rations.

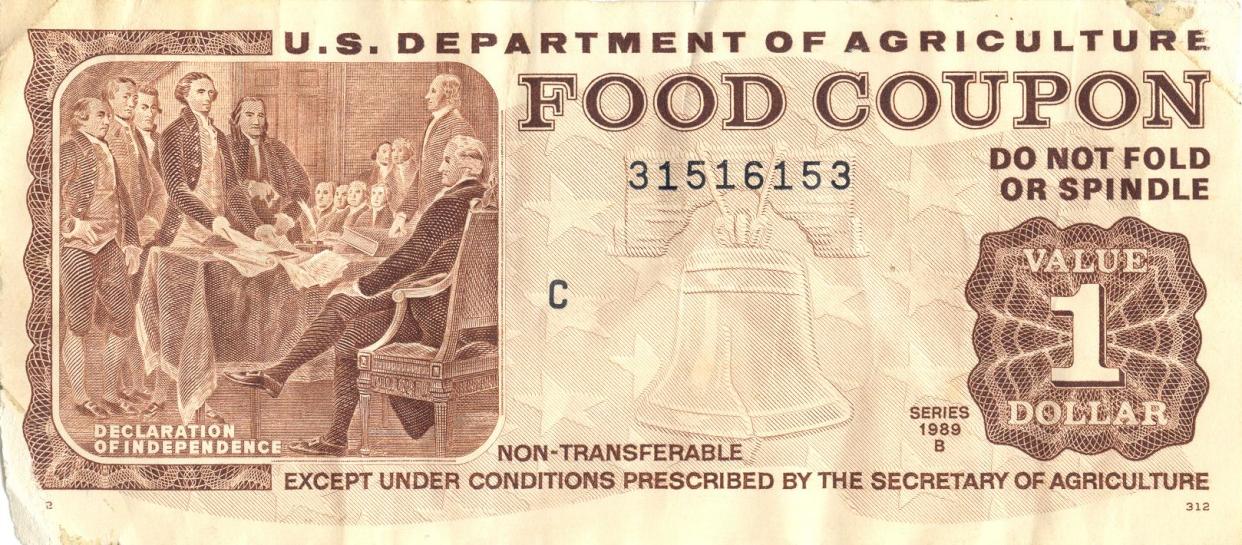

But I couldn’t shake my memories. Kids snickering at the bright orange ticket I traded for my free lunch in the school cafeteria. Social workers constantly questioning my mom to prove we were poor enough to merit help. My dad pulling food stamps (which looked like Monopoly money) out of his wallet under the disapproving eyes of a cashier, who always seemed to scrutinize our groceries. I always wished I could disappear. I dreaded experiencing those feelings again.

If I wasn’t willing to suffer the disapproval of a cashier, why was I willing to suffer the scrutiny of thousands of readers? I still wonder about that. Maybe the answer is that writing about poverty gives me control of the narrative. I can tell you that my failure isn’t due to laziness. I can’t explain that to the judgy lady in line behind me at the grocery store.

So I used poverty as a stepping stone to a career as a freelance journalist and eventually got a salaried job as an editor for a startup. I was proud of myself for making it on my own, and it felt so good to go to the store and buy whatever I damn well wanted. I thought I’d escaped. After a lifetime of benefiting from the kindness of friends, I loved being the person who could pick up the check.

That ended 14 months ago, when my publication was scrapped because my company was in danger of going under. It’s OK, I told myself. I’ll just go back to freelancing. But the world had changed.

Fortunately, Oregon social services have also changed. When I finally filled out the Snap forms online, I was not questioned, and my request was expedited because I had less than $75 in my bank account. I had been really anxious about the process, and it was a relief that it was much more humane than it had been in the 80s. But I still had a heavy heart that it had come to this.

Within three days of applying, I received my Oregon Trail card – a more discreet way to pay than the embarrassing “Monopoly money” of my childhood. So why did I cry when I saw that I’d been approved for $271 of free food this month?

Irrational shame and sense of defeat aside, have you been to a grocery store lately? No, I wasn’t expecting more. Yes, I am grateful to be approved for the highest amount available. And yes, it will really help. But surviving on this budget will require real thrift. Luckily, I’ve been training for this my whole life. And I’m not just talking about watching my dad buy quick-sale meat.

I tried to think of budgeting as a game. Instead, I found myself worrying about what to wear, checking if my fingernails were clean, and wishing I didn’t have a cold sore. I was also trying to make an important decision. It’s an hour’s drive to the nearest grocery store. Would I spend my $271 in one trip to economize on gas money? Or should I spend more money on gas in order to get fresh food later in the month? I decided on two trips, with the hope of narrowing it down to one once my garden starts producing.

Normally I’d first visit the Grocery Outlet to look for deals, and then go to Kroger to pick up the rest of my list. But I wanted to confront my cashier anxiety head-on, and I figured people were more likely to be judgmental at a conventional grocery store.

At Kroger, I found that spending government money didn’t make me keener to buy four chicken sausages for $9.99. Nor did I think it was a great idea to spend $2.99 on a fistful of organic broccolini. I kept to the basics: chicken thighs, conventional vegetables, fruit, yogurt, bread. The only luxury item was good coffee – which was on sale.

As I approached the line, I could feel my anxiety ratcheting up. In a moment of weakness, I was tempted by the automated checker. But I knew that wasn’t going to help me face my shame, and it seemed particularly hypocritical to use one after complaining so much about robots stealing my job.

As I waited in line, I looked at the blond cashier and wondered if she was the type of Republican who views poverty as a moral failing. All her facade told me was that she was a fan of the Oregon Ducks. She smiled as I approached.

I think Americans experience a particular type of shame when we sink

“Um, I’m using a Snap card for the first time and I’m not sure how that works!” I blurted. Was I trying to get credit for being a first-timer? Maybe. I felt disgusted with myself for that, but Melissa was all grace and efficiency, and she didn’t give me side-eye for my three pounds of fancy coffee. I ended up spending $150 on two bags of groceries and some vegetable starts, which I was pleased to discover are covered by Snap.

At Grocery Outlet, I found cheaper sausages and mustered the nerve to spend my scant cash on face wash and wine. I scanned the cashiers and chose an older woman with purple hair and matching coffin-shaped earrings. She looked like the type of lady who thought poor people should be allowed to drink wine too. She was kind when the woman in front of me worried her card would be declined, and she didn’t blink an eye at my wine. I walked away with a lighter heart and a hefty bag of food for $50.

Despite this experience, I expect I’ll still feel nervous as I approach the grocery line. You never know who you’re going to get. But the real problem is that I have about 10 days of supplies and $71 remaining. It’s a good thing I have a short-term gig cleaning houses and a friend who keeps me supplied with dry goods from the food bank. He keeps telling me I should go, and maybe my hometown bread line is the next step in conquering my neurosis.

Capitalism is a rigged system the world over, but I think Americans experience a particular type of shame when we sink. “The American dream” has taught us to believe that we’ll prosper if we’re good enough. That’s simply not true any more, and it really never was. I can understand this intellectually, but hope springs eternal: Writing about poverty for the Guardian? Maybe I’ll finally make it!

That part of my brain is ignoring that I’ve been writing about food insecurity to international audiences for 14 years. A lot of that time, my fridge was empty. I guess the difference is that now it’s full. I just wish it were due to my decades of hard work.