Western leaders have a vision for a future Palestinian state

Here’s the dream: Israeli special forces stage a lightning raid from the eastern Mediterranean coast and free its hostages, all 199 of them. The Israeli Defence Force then rolls in and, over a period of six to eight weeks, buries Hamas and its ability to wage war in the vast subterranean tunnel network beneath Gaza.

With the area demilitarised, a new front line is drawn within Israel and a good-sized buffer of no-man’s land created behind it. Gaza is administered by a caretaker coalition of Arab nations including Jordan, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates before the Palestinian Authority takes over. They all step up at the bidding of Joe Biden, the US president.

Gaza then grows over a decade or more to become a new Singapore on the Med. And a peace dividend – social as well as economic – finally creates the conditions for an independent democratic Palestinian state to be established, sitting cheek by jowl with Israel. The Arab-Israeli conflict, which has raged on and off since 1948, is finally over.

“I tell you what many of us will want to happen, and we then need to have a reality check,” says Prof Manuel Trajtenberg, an economist and executive director of the Institute for National Security Studies in Tel Aviv. “The idea is to take this terrible event, and turn that into an opportunity; to do something that was unthinkable just before … a long term settlement with the Palestinians.”

With missiles raining down on Gaza, the Arab street erupting from Beirut to Tangiers and US aircraft carriers manoeuvring within striking distance of the Iranian capital Tehran, you could be forgiven for thinking that a dream is all it is.

It’s not for nothing that the UN’s Middle East peace envoy warned yesterday that the region was on the brink of a “deep, dangerous abyss” that could change the trajectory of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, if not of the Middle East as a whole.

But diplomats have got to think big, and many are now turning their attention to what should happen in Gaza once the fighting stops.

“The reason Mr Biden became so involved from the very first day is because the Americans look at it as an event that has far reaching geopolitical implications,” says Mr Trajtenberg, pointing to “the alignment” taking shape between Iran and Russia, with China in the background.

“It’s a significant development in the context of great power competition … a reconfiguring the Middle East as part of that much wider global geopolitical strategy.”

Other than a handful on the far-Right, most agree that occupation of the 25-mile long Gaza strip is not a good option for Israel once the shooting stops. Israel pulled out of Gaza in 2005 for good reason.

If it were to try and hold the territory again it would almost certainly be fighting a new insurgency. Already the IDF is badly stretched in the West Bank where encroaching Israeli settlements create constant flash points.

So the Gaza question will become: who should Israel hand control to and who might be tempted to pick it up?

“Occupation is not an option,” one former IDF officer told The Daily Telegraph. “It makes no sense. It’s a big bit of land. It’s two million people. The front line must be in Israel, not Gaza. Some say there should be a buffer [zone] behind it – some no man’s land.”

Perhaps a partial annexation was what Eli Cohen, the Israeli foreign minister, was alluding to yesterday when he was quoted as saying: “At the end of this war, not only will Hamas no longer be in Gaza, the territory of Gaza will also decrease.”

The bigger picture: two-stage solution

The bigger picture, however, is of international diplomacy and finding a way of convincing neighbouring Arab nations whose interests are aligned with the West to help restore stability to Gaza and work towards what many regard as the only long term solution – the creation of a Palestinian state.

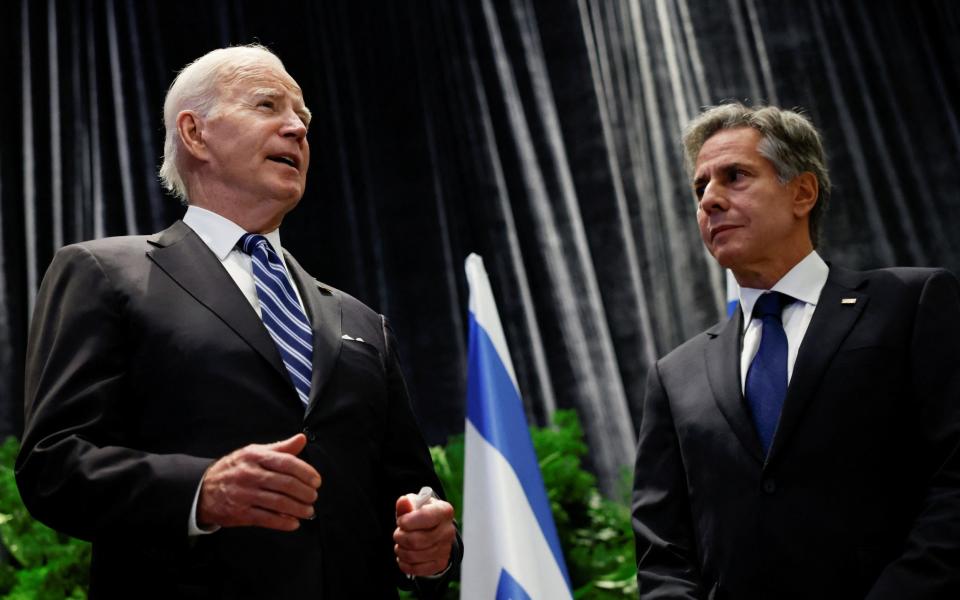

This is what Mr Biden and Antony Blinken, the US secretary of state, are said to see as the ultimate prize.

“There are a few stepping stones,” says Mr Trajtenberg. “The first is that Hamas has to be eliminated as a military force.

“Anything short of that will impede any progress … there is common interest in making that happen across the region.”

The second is to convince countries including Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates and others to help administer the rebuilding of Gaza until the Palestinian Authority is willing to take it on, he adds.

Giora Eiland, a former head of the Israeli National Security Council, is supportive of the diplomatic approach but not optimistic it can be work.

He worries that even if Hamas can be flushed from Gaza, Hezbollah will still need to be tackled in the north. The days of Israel putting up with terrorists on its borders is over, he says.

And he is sceptical about the propensity of Israel’s friends and immediate neighbours to roll up their sleeves to help, even if peace can be created.

“No one, no one in the world… is [currently] interested in being responsible for what is happening in Gaza after this war. So there is a big vacuum,” he says.

“The best position that they can choose is not to be accountable for anything; not to contribute anything and only to continue to blame Israel. This is the policy of all the Arab countries today, including Saudi Arabia and others”.

At best, Mr Eiland sees a classic two-stage solution – a prolonged military campaign, followed by some sort of negotiated political fix, grand or otherwise.

“We can expect that after the military operation, whatever it means, however long it will take, that there will be a transitional period,” he says.

“During that time there will be a lot of uncertainties, and even chaos, before it will be possible to establish something stable.”