‘I want to take the audience further than they’d like’: Kwame Kwei-Armah on Beneatha’s Place

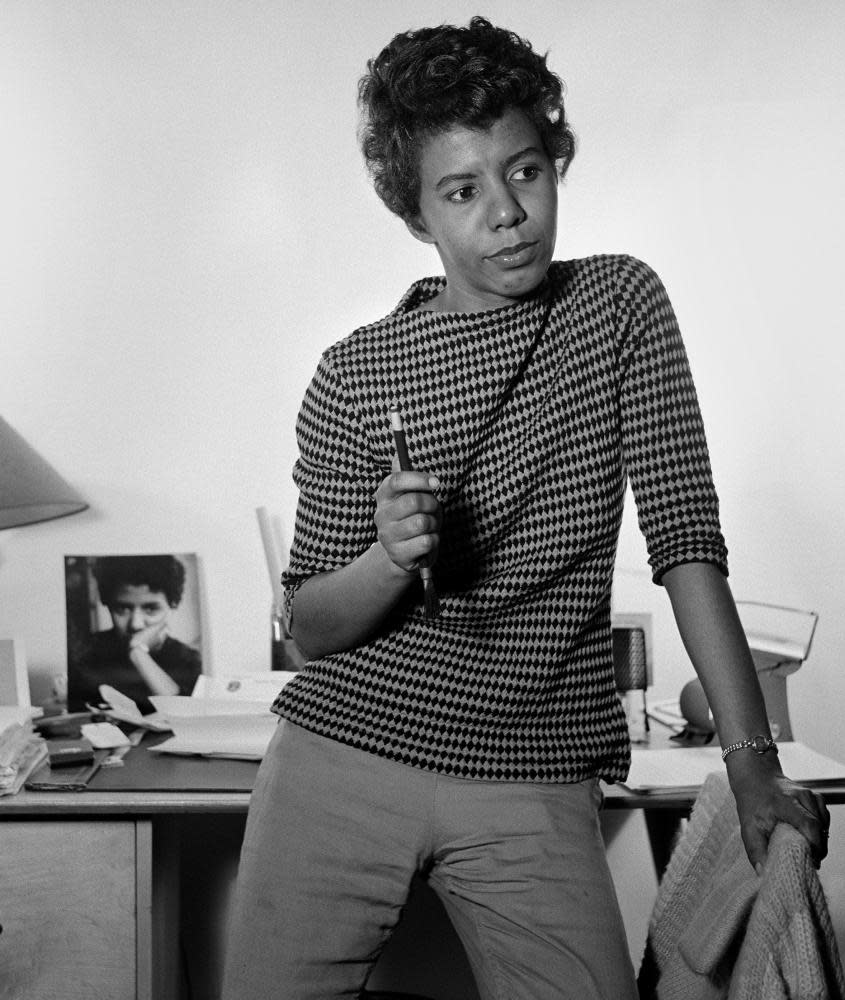

As we get ready to open Beneatha’s Place at the Young Vic theatre in London, it has been beautiful to dance again with the genius that is Lorraine Hansberry. She was an Afrofuturist whose plays spoke to what was happening at the time and things that were yet to happen in Africa. When we think about Black politics, we don’t often think about the 1950s and how radical it was. Hansberry was one of those 1950s radical Black thinkers who were standing on the shoulders of those who had gone before, such as Marcus Garvey, and laying the groundwork for those who came afterwards, such as the civil rights movement in the 60s and the Black Power movement of the 1970s.

My first encounter watching her play A Raisin in the Sun was here at the Young Vic more than 20 years ago, in a production starring Lennie James. I remember being moved by the portrayal of this Black family’s aspirational dreams and relating to a mother who is trying to negotiate with her son’s perception of his own masculinity and what he should be doing with his life. Yet, of all the characters, I found myself most drawn to and resonating with Beneatha. She was Afrocentric at a time when that was not fashionable, she wanted to redefine herself and be someone else and, at the end of the play, as a diasporic African, she articulated her desire to want to go to Africa.

Her story stayed with me and 10 years later I wrote Beneatha’s Place, a dance between A Raisin in the Sun and Bruce Norris’s play Clybourne Park. Revisiting the play today, another 10 years on, this time as writer and director, I now see Beneatha’s Place as a continuation of A Raisin in the Sun but also a contemporary reading of today’s culture wars about race. In Act 1, Beneatha, beautifully portrayed by the magnificent Cherrelle Skeete, has left the US to come to Nigeria with her husband, the rising political star Joseph Asagai, played by our wonderful Zackary Momoh. They arrive as Nigeria is on the brink of independence and must navigate being at the crossroads of this historical moment.

Act 2 brings us to the present day and speaks directly to the US debate on African American race studies and to Black and Brown audiences in the UK who feel disenchanted and fatigued with the focus on race. In a way, this is an investigation into who owns the intellectual property of race.

The play features “negro memorabilia” which we might think belongs to another time. But I found it really illuminating earlier this year when a pub in Essex made the news after its collection of golly dolls was confiscated by the police. Interesting that they were confiscated, and then sympathetic people started posting their own dolls to the pub owners to say “No, this is something that we support”. Can we truly say that these kinds of objects are in the past?

Beneatha’s Place is an investigation into what history means, who has ownership of it and the narrative around history. I think the culture wars are about just that; one side furiously defending a history that maintains the status quo, and the other furiously attempting to modernise in the hope of rebuilding the pathways that got us here, with honesty. In the play we look at it from the African American and the diasporic African point of view but also from the contemporary white point of view in terms of how one negotiates changing rules and the changing way that we discuss issues. I’m sympathetic to the process of adaptation; you have to re-examine your blinkers and find new languages, new terminology, learn and teach yourself how to renegotiate the here and now.

It is a big subject and to come at this in a heavy fashion would be very boring. Act 2 is set up to have us look at ourselves, laugh at ourselves and with ourselves. One of my favourite lines in the play is when one white character says to another white character, “Let’s talk about your white privilege” and he replies, “I’d rather count the wrinkles on my dog’s balls”. If I want to catalyse a debate, for my money, humour is one of the most potent weapons we have.

I believe that theatre is the space to hold conversation with purpose and that the people who can make change come to this space. Through this production, I want to incrementally take the audience one step further than they want to go. I want white audiences to go away thinking: “How do I negotiate with my fragility and how does the world accept that my fragility is part of my growth?” And also, how do we as diasporic Africans negotiate with the issues of our history as it conflates with race? Do we let it go and not dance with race any more, and if we yield that ground, who will take it over?

• Beneatha’s Place is at the Young Vic, London, until 5 August.