The victims of Jack the Ripper deserve better than London’s lurid tours

And there, outside Aldgate East station, is the man. A strange-looking fellow, cadaverous, softly spoken, with an accent that’s somehow not quite of this world. He exudes a charismatic menace in the Whitechapel gloom.

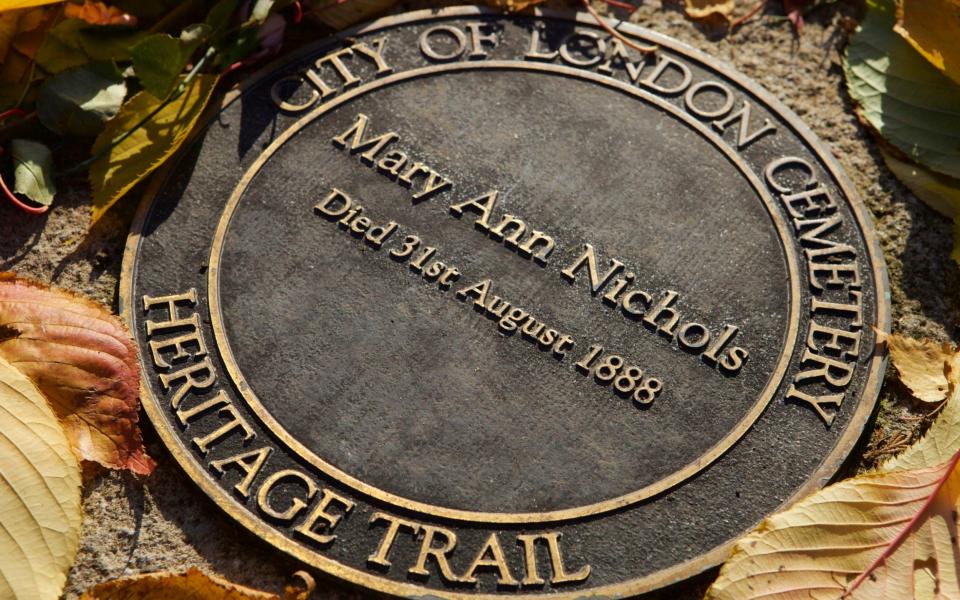

Between April 1888 and February 1891, Whitechapel and Spitalfields were rocked by the horrific murders of 11 women. Five of these, in the autumn and winter of 1888 (the “canonical five” of Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes and Mary Jane Kelly), were suspiciously similar and savage, leading the police to believe that a single killer was responsible. Many had suffered appalling mutilations after they had been murdered. The enormous police investigation, and eager press coverage, triggered a climate of fear and fascination, which meant “Jack the Ripper” became an international sensation, and remains so – with the recent discovery of a never-before-seen police file garnering fresh headlines, 136 years later. Over the next two hours, we are taken to the sites where the canonical five met their violent, sudden ends.

As someone who has been leading immersive historical tours of London for the best part of a decade to supplement my often parlous income as an author, I know that one of the biggest challenges is how, when you’re regaling people with the same old stories, you keep things fresh. I like to craft tours around things I actively want to bring back, or at least which serve as a foil to the present-day in some way – the face-to-face conviviality of London’s original coffeehouses in a world of Starbucks ennui, for example – thinking of it more as preaching than guiding, and that keeps things fresh. But to each guide, their way.

For ours, that night, there was one thing and one thing only that wrenched him from the fug of his well-rehearsed routine, so it seemed to me: violence. Articulating the motions of Jack’s knife, his hands slicing through the air: that’s when our guide came alive. In the crowd, I saw wide, titillated eyes, conspiratorial glances and a collective intake of breath, as though a curtain were being whisked open.

We are about 35, huddled together. You can join the murder trail on any night of the week, sometimes in the afternoon too. All you have to do is buy a ticket from one of the many operators, and go to a certain Tube exit at a certain time. Then your bloody odyssey awaits. We don’t actually visit all the murder sites – some are “too far away, we’d be here all night” – instead we are teleported there courtesy of printed-out photographs flapping in the wind. The crowd is overwhelmingly American.

There were some clichés. Most were forgivable on a murder walk, but not all. “Things were very different back then,” we learn, “not at all like today.” Our guide proceeds to paint a portrait of the Victorian East End as the heart of darkness itself, a nightmare realm of grinding poverty and unshackled depravity. This is not without truth – but it’s a little parodic.

In truth, some of Jack’s catchment area, especially Spitalfields, had pockets of affluence, including the fine 18th-century townhouses that had originally belonged to Huguenot master silk-weavers; and in Whitechapel itself, philanthropists like George Peabody had built fledgeling social housing for the “deserving poor”; vast hospitals, too, not least the Royal London Hospital which still towers over Whitechapel Road like a benevolent Cyclops.

I find the setting compelling, more so than the tour – it’s still the grimy old Whitechapel of Ripper lore but a sparkling new one too, of cocktail bars and sushi joints, gleaming glass boxes housing City financiers and enormous pieces of state infrastructure shooting into the sky.

We enter an especially crowded plaza but people are not moving quite how you’d expect, and it slowly dawns on me that every single person in my field of vision is on a Jack the Ripper tour: not just our guide’s, but seemingly two or three others besides. It’s then that the absurdity of the whole enterprise sinks in; that almost a century and a half after a spate of suspiciously similar murders were committed, vast swathes of Whitechapel have, each evening, become a commemorative playground.

At one point, a slightly-ajar window catches the attention of our guide. He peers up, uneasy, and beckons us forward. He speaks in more hushed tones. There have been complaints, I later learn, from Whitechapel residents that graphic accounts have been floating in from the street on warmer evenings as they tuck into their evening meal.

Fascination with the Ripper was fuelled by another feral beast, residing a little further to the west. Along the muddy, rambling thoroughfare of Fleet Street, printing had been transformed into a mind-moulding instrument of mass communication, with millions of papers published each week. New tabloids like the weekly Illustrated Police News, which came into its own during the Whitechapel murders, were astonishingly visual, capturing the imagination of everyone from boot-blackeners to baronets. A sort of early Crimewatch, it had lurid, brief, titillating captions like “the Revolting and Mysterious Murder of a Woman in Buck’s Row, Whitechapel” and “Ready for the Whitechapel Fiend, Women Secretly Armed”, showing women hiding pistols and knives beneath their crinoline skirts.

I ask whether Jack the Ripper could, to some extent, have been an invention of the media – manna surely for journalists wanting to sustain their readership, and hasn’t this had a formative influence on our enduring fascination with Jack?

“No,” comes the answer. The crowd regards my question with annoyance. They want more murder.

So what explains our enduring fascination with the Ripper? Why are there no walks commemorating the numerous other serial killers from the modern era that have stalked the streets of London? Could it be that Jack the Ripper hails from a remote mental realm of gas lights and top-hatted men whereas more recent murders are a bit closer to the bone? Could be. But the huge popularity of true crime on Netflix and podcasts suggests that this only takes us so far.

The main reason – surely – is that unlike the vast majority of serial killings, those attributed to Jack the Ripper are unsolved (and, now, unsolvable). If you have a killing spree, but no one has the first idea who the killer is – or rather, people have all sorts of ideas but no one knows if any of them are true or not – there’s the perfect formula for enduring fascination. It’s this that turns us into amateur sleuths; this which, in my view, the journalists and editors of the Fourth Estate exploited to commercial effect in the autumn and winter of 1888, and which continues to be exploited by a wide range of media today.

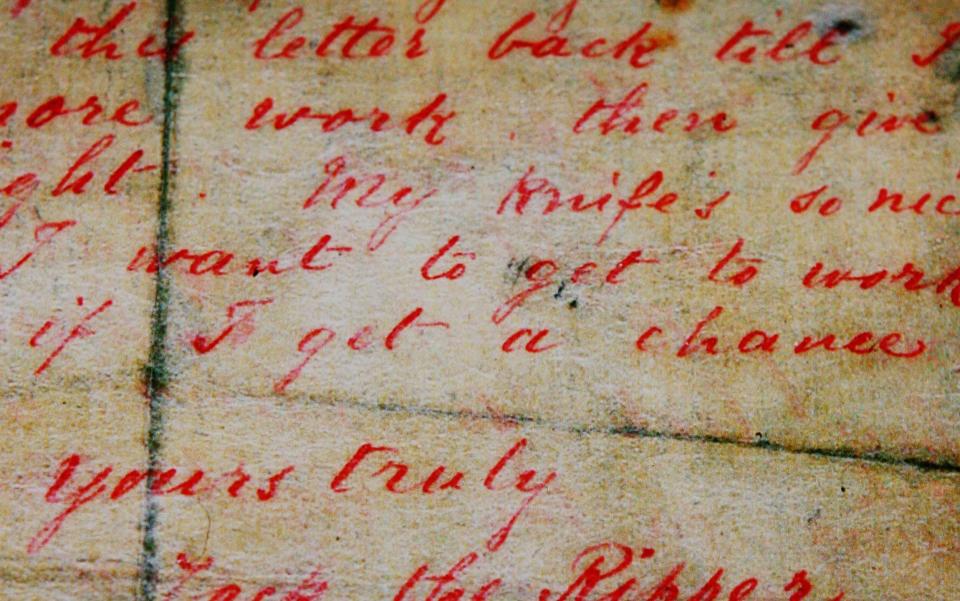

The savviest journalistic trick at their disposal, the thing that aroused people’s interest to obsession, was to publish – unmediated – the “words” of the serial killer. Written in a curly, elegant hand, in blood-red ink, the “Dear Boss” Letter is an artful piece of menace indeed, but it’s a clever piece of characterisation too. It is the first time “Jack the Ripper” is mentioned – the source of the legend. Received by the Central News Agency three weeks after the second murder, its courteous calligraphy is at odds with the tone and style, best characterised as jejune Gothic. The short, sharp sentences are menacing but basic with many childlike turns of phrase: “I gave the lady no time to squeal”; “my knife is so nice and sharp.” There is also an unmistakable British or even London twang: “Grand work the last job was”; “give it out straight.” A sequel followed, the “saucy Jacky” postcard, on Oct 1 1888.

Do they read like the work of a skilled wordsmith – a journalist, say – emulating an East End serial killer? For sure. They were initially dismissed as what in all probability they were: hoaxes, but there was just enough doubt for the police to take them seriously. It seems to me that both – along with the many other, less convincing ones that were received in 1888-1891 – were part of a well-orchestrated media campaign to keep the story in the public imagination, where it has remained ever since. In 1931, a journalist called Fred Best reportedly confessed that he, along with a fellow hack at The Star had penned the murderous letters “to keep the business alive”.

Because his identity is unknown, each successive generation has made of him whatever monster they will: a Jack of all trades. For contemporaries, he was a physical embodiment of the sordidness, deprivation and poverty of the Victorian East End. By the 1960s, he seems to have become more aristocratic, a psychopath in a top hat exploiting everyone and everything. This century, it has been more fashionable to produce forensic enquiries, often adopting modern-day crime-solving methodologies. Bruce Robinson, the writer and director of Withnail & I, spent 15 years producing his extraordinary door-stopper contribution entitled They All Love Jack. Since Hallie Rubenhold’s book The Five was published in 2019, there has been a refreshing shift away from sensationalising the killer’s crimes to illuminating the lives of those he murdered; now, if the Americans on the tour are anything to go by, he is considered some sort of timeless representation of the lethality of London streets, plagued by knife crime.

The guide leads us into a car park. I think we are at the site of Miller’s Court, where the final victim was found, or at least near it, or perhaps nowhere near it because it’s too far away, but what happens next is profoundly moving. He removes something from a sports bag he’s been mysteriously carrying all this time. He points it at a wall and starts fiddling. The image wobbles and flickers but then the coroner’s sickening photograph of Mary Jane comes into some sort of focus and the crowd falls silent.

It is then, in the stunned silence, staring at this 136-year-old photo, that the human tragedy of the Whitechapel murders becomes palpable. The women feel, for the first time, real. I wish our guide had brought them to life as well as he brought them to death, as it were. He does acknowledge they were not just “career prostitutes” but those who were driven to it by desperate circumstance. But there’s not much empathy beyond that. I don’t get the impression he’s read Rubenhold’s bestselling book, which reveals “the five” were, at points, balladeers, coffeehouse mistresses, domestic servants, printers and more, united by the misfortune of converging upon Whitechapel when there was a killer on the loose, but so much more than Jack’s roadkill. I wonder how the tour might be different with a female guide, for example on one of Katie Wignall’s feminist Ripper tours.

The tour is over. There’s a round of applause – slightly muted because it feels distasteful applauding such horrific acts of violence. The man tells us that he lived – lodged – in Whitechapel all the time he was doing his research. He gets out a little card machine and tells us he likes tips before walking ruefully into the rain.

Dr Matthew Green leads immersive historical tours of London every weekend, including the Coffeehouse Tour, Medieval Wine Tour and Gin Tour. He is the author of Shadowlands: A Journey through Lost Britain, published by Faber. You can buy a copy here.