You’ve Never Seen an Architecture Exhibition QUITE Like This

The Sharjah Architecture Triennial 2023 opened in the United Arab Emirates coastal city of Sharjah on November 11. The citywide festival, curated by Nigerian architect Tosin Oshinowo, features a wide array of projects from 26 countries, assembled in various locations across the city—from Sharjah’s Old Al Jubail Vegetable Market to a historic slaughterhouse, a school, and a mall. The show, titled “The Beauty of Impermanence,” makes a playful, investigative argument for scarcity as a primary instigator of modern innovation. The exhibition, now in its second edition since its debut opening in 2018, will be on view until March 10, 2024.

The show is a geographical counterpoint to the architecture fairs of the West. The participants include both emerging and established practitioners—largely from sub-Saharan Africa, with other participants from the Middle East, South America, Europe, North America, and Southeast Asia. “The theme is relevant, timely, and in line with our collective moral compass that acknowledges that there is no—and there should be no—single center,” Oshinowo tells ELLE DECOR.

Among the many new and niche practices represented were several whose work was previously featured in ELLE DECOR like Limbo Accra, Formafantasma, and Nifemi Marcus-Bello. “Geography and cultural perspectives influenced the selection of participants, but most important was their deep engagement with practice that responds to my theme,” Oshinowo says. “Their duality of perspective allows them to champion innovation as a fundamental requirement for survival.”

Below, we outline a few of our favorite installations and projects on view.

Olalekan Jeyifous’s Retro-Futurist Takeover of a Vegetable Market

Very few of the projects on view take the form of scale models—the go-to format for architecture presentations. Instead, there are large-scale installations, interactive rooms and structures, landscapes for rest and reflection, isolated spaces for mourning, and sculptures that scale the edge of the architectural. Olalekan Jeyifous, a Nigerian American architect and fine artist, presents a series of digital images and 3D models imagining what Sharjah would look like today if instead of succumbing to the concrete-driven commercial real estate boom of the 1970s and 1980s, the city had instead invested in its fishing and pearl-diving heritage, organizing itself around waterways and shaded communal spaces. In Jeyifous’s retro-futurist view, urbanism bows instead to community and the sea. Poetically, his installation is situated in the city’s vegetable market, one of the six locations across the city used for the triennial. The market was once right on the coast but now faces a new vegetable market on man-made land.

Cave_bureau’s Museum in a Slaughterhouse

Elsewhere in the city, in an old slaughterhouse, Nairobi-based Cave_bureau installed the ninth iteration of their Anthropocene Museum, a research project interrogating human existence and our species’ relationship to the earth. In the exhibit, visitors are shuttled through the slaughterhouse, forced to consider consumption from the point of view of the animals we consume.

A sculpture by Lebanon-based artist Adrian Pepe awaits inside, taking the form of a larger-than-life, multiroom intestine made of sheep hide, a meditation on the by-products of meat and the craft traditions they have birthed—from clothing to home goods, as well as the circle of life starting from inception. “In life, only death is certain; everything else is in flux,” reads Cave_bureau’s exhibition text.

Thomas Egoumenides’s Landfilled Labyrinth

Tangos with the ancient pop up here and there, like in Thomas Egoumenides’s The Ship of Theseus. Repurposing old thread spools, the French-born, Tunisia-based architect challenges our hyperconsumerist economies with a playful labyrinthine installation. Placed on threaded rods, the spools make up a maze, like that of the minotaur in Theseus’s story, welcoming guests to get lost among materials that would otherwise have fallen into a landfill.

A Space for Contemplation by Sumaya Dabbagh

There are moments of the more traditional, like Sumaya Dabbagh’s Earth to Earth. The Saudi-born, Dubai-based architect is one of the first women of the modern era to design and construct a mosque (and is currently working on her second). Her mud-brick, outdoor sculpture could similarly be taken as a spiritual space for contemplation. Organized as a spiral, with two entrances, it is quietly complex, with walls that tilt inwards as they ascend. Regardless of the time of day, in at least one point of its interior, visitors can find shade.

DAAR’s Concrete Tent

Deeply poetic in terms of location and content is Stockholm-based architectural duo Sandi Hilal and Alessandro Petti of DAAR’s Concrete Tent. It stands in the middle of the abandoned desert village of Al Madam as an impermanent space of mourning for the displaced. Its name, materials (wood beams and sackcloth with a concretelike coating), and structure recall refugee tents, specifically those of the Palestinian displaced (Hilal is Palestinian) and consider what it means to gradually make impermanent places of rest more permanent. The installation asks, When we accept that we must plant new roots, do we forsake the ancestral ones we left behind?

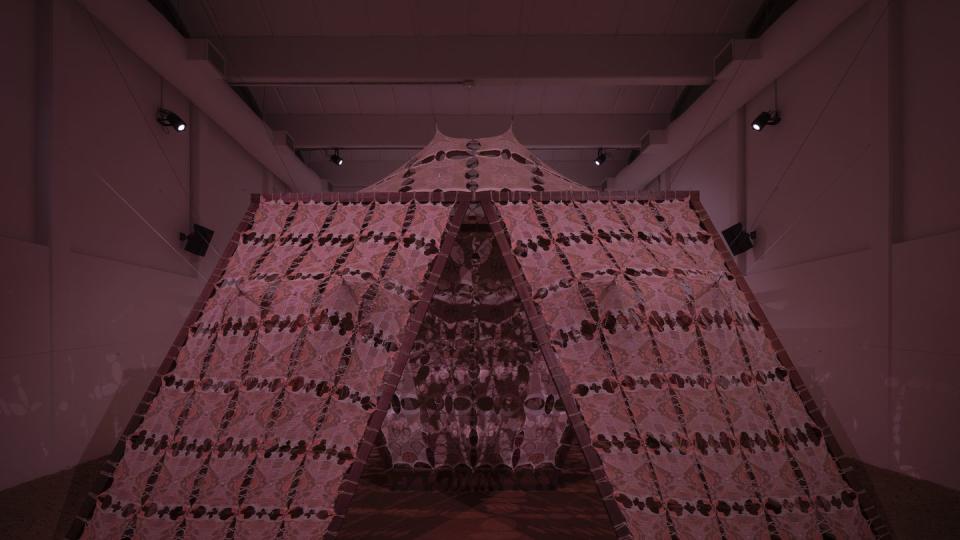

Yussef Agbo-Ola’s Crocheted Pavilion

Another tent, perhaps closer to a temple, constructed with the intention of meditation over mourning, also attracted notice. London-based architect and artist Yussef Agbo-Ola, who grew up in rural Virginia in a Nigerian, Cherokee, and Black American household, organized his room-size construction out of crocheted plackets made of organic materials held together and stretched over a wooden frame. Within the structure are spaces for calm reflection, with incense burning from clay pots. The entire structure is surrounded by cracked earth, which can be seen as a metaphor for global warming. More impressive even than the structure itself is its planned lifespan: Once the triennial ends, the tent will move to the Amazon forest (where Agbo-Ola is based part of the year) to be consumed by the earth.

You Might Also Like