Two Way Mirror by Fiona Sampson review – a fine life of Elizabeth Barrett Browning

“How do I love thee? Let me count the ways,” asked Elizabeth Barrett Browning in 1850, unwittingly turning herself from one of Britain’s pre-eminent poets into a Valentine’s card fixture. It wasn’t just the words, which are still lovely, but the way they tend to be read in conjunction with the story of her clandestine courtship by fellow-poet Robert Browning. In 1846, after a year and a half of epistolary romance and secret meetings, young Browning famously burst into the 40-year-old’s London sickroom and whisked her to Italy and a new life of sunshine, sex and lyric poetry.

Of course, this biographical reading would have appalled Browning, who spent a career trying to break the automatic identification between the “I” of the poem and the “me” of the poet. Chances are such a reductive approach would have unsettled Barrett Browning too. She saw herself as a public prophet rather than as what she scathingly called a “fair writer”. Her first publication as a precocious 14-year-old had been an account of the Battle of Marathon, and she went on to tackle big, gnarly subjects including the iniquity of laissez-faire capitalism (“The Cry of the Children”) and the struggle of Italy for political self-determination (“Casa Guidi Windows”). These days we forget that when Wordsworth died in 1850 it was Barrett, rather than Tennyson, who was most often mentioned as the next poet laureate.

It is this publicly engaged Elizabeth that Fiona Sampson sets before us in this fine biography, the first since Margaret Forster’s more than 30 years ago. For her frame and point of reference Sampson uses Aurora Leigh, the verse novel that Barrett Browning wrote in 1856, which tells the story of a young female writer’s career, specifically an artist’s development. At first glance this might seem to mark a retreat to the personal and the biographic, but Sampson’s point is that Aurora Leigh provides us with a map and model for how Barrett Browning forged a new relationship between female subjectivity and public utterance. Less happy perhaps is Sampson’s decision to concoct chapter titles along the lines of “How to be autonomous” and “How to manage change”, which makes it sound as if Barrett was also an incorrigible consumer of self-help manuals.

Guilt about her background, Sampson thinks, accounts for Barrett’s claim that she herself had ‘the blood of the slave’

The content, though, is spot-on. Sampson is particularly interested in Barrett Browning’s personal and political entanglement with empire and race. “Ba”, as she was always known, was born in 1806 into a British Jamaican plantation family. Her father, the dynastically named Edward Barrett Moulton-Barrett, had inherited his sugar fortune off the lashed backs of slaves and yet, as a devout nonconformist Protestant and political Liberal, he was on the side of putting things right. Ba was even clearer on the subject, producing in 1846 “The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point” as a contribution to the fund-raising drive of the American abolitionist movement.

Guilt about her background, Sampson thinks, must account for Ba’s well-known and intriguing declaration to Browning that she herself had “the blood of the slave”. A couple of decades ago, critics got excited, believing that not only was she admitting to being of mixed race, she was acknowledging her shame about it. Sampson, by contrast, takes the view that she is referring to her guilt at being the daughter and granddaughter of slavers. Specifically, she knew that her private income, the one that allowed her to elope with penniless Browning and set up a series of comfortable homes in Italy from where to sing songs of political liberation, was horribly compromised.

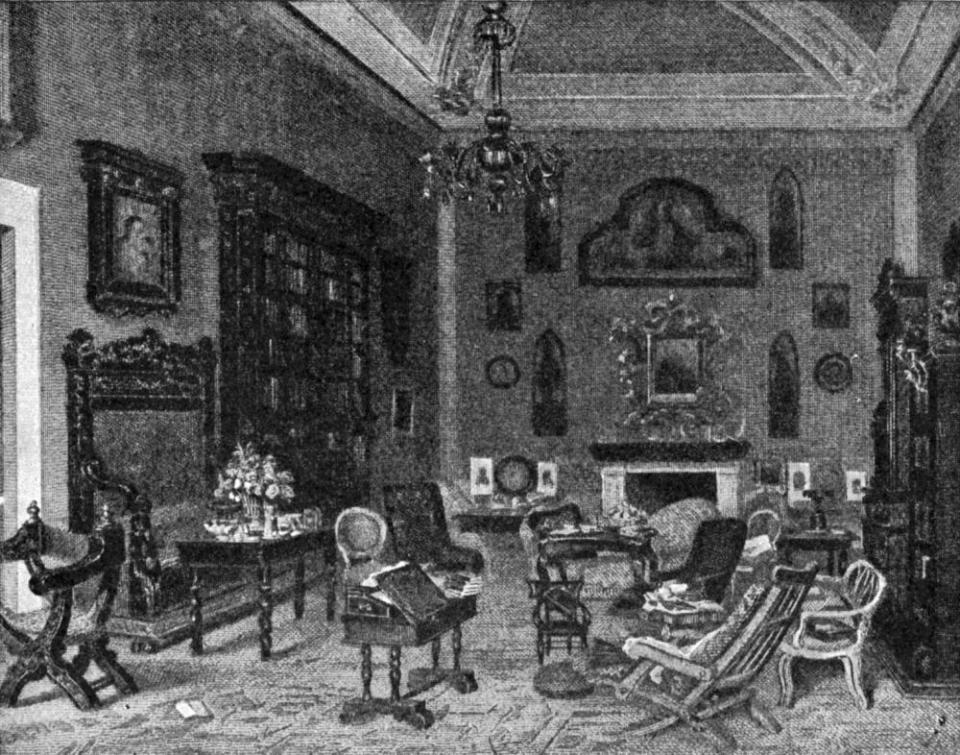

Another old biographical knot that Sampson is keen to untangle is the question of whether Moulton-Barrett really was a gothic monster. He has gone down in literary history as a bullying patriarch who put his children under virtual house arrest and refused to countenance any of them marrying, even the boys. In fact, this view owes more to Charles Laughton’s creepy turn as Mr B in the Hollywood film of 1934 The Barretts of Wimpole Street, based on the hit play by Rudolf Besier. Sampson helps us to see Moulton-Barrett more generously, as an insecure parvenu who never fitted in with the gentry of Herefordshire among whom he lived from the 1820s. He may have twice been made sheriff of the county, but there was no gainsaying the tackiness of Hope End, the Moorish mansion complete with minarets that he built in the rolling Malvern hills. Sampson calls the whole edifice “outsider art”, which is probably being kind.

Even so, Sampson is not too fastidious to deprive herself – or us – of the schlockier pleasures of biographical speculation. In 1989 Anthony Burgess toyed with the idea that, as Balay dying in June 1861, Browning slipped her an extra big dose of morphine to polish her off. After all, she had already ruined her body through drug addiction, so no one would be any the wiser. And they had been quarrelling recently – her obsession with spiritualism was driving him mad and he hated the way she dressed up their young son in girls’ clothing. Sampson is too judicious to say whether she really thinks that Browning bumped her off, but she understands enough about the pleasures of transgression to leave the possibility in play.

• Two-Way Mirror: The Life of Elizabeth Barrett Browning is published by Profile (£18.99). To order a copy go to guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.