The truth about the ‘bleak future’ of ski holidays

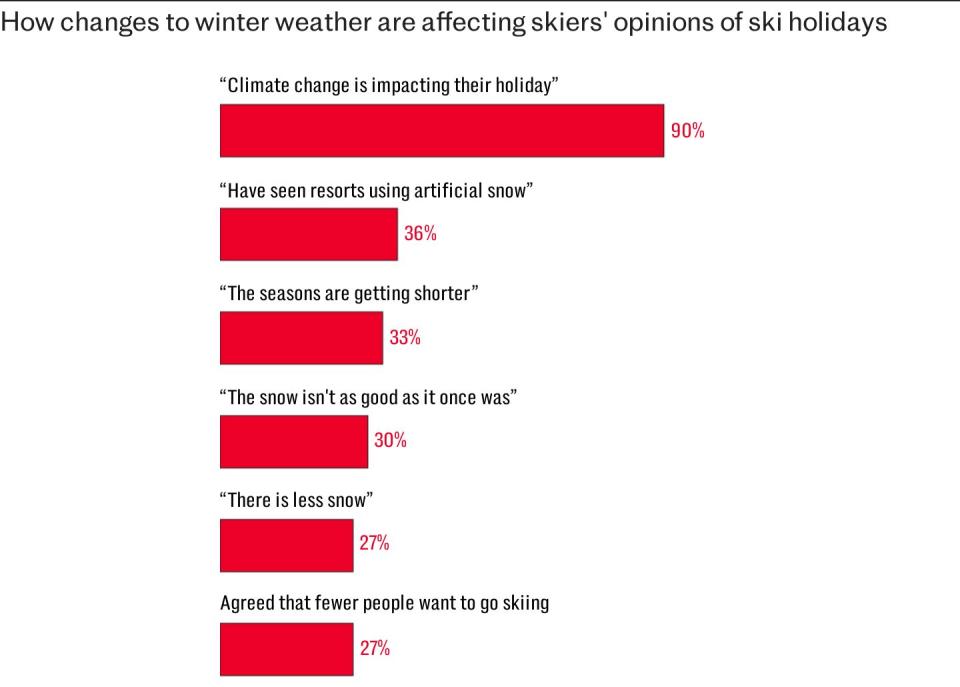

Ski holidays face “a bleak future” as climate change wreaks havoc in resorts around the world. Last-minute bookings to only high-altitude resorts and alternative activities off the slopes will increasingly become the norm, as the shape of ski holidays changes.

The past two years — 2022 and 2023 — have been both the hottest globally and the worst for melting glaciers on record. If you’re passionate about holidays on the slopes, experts say the warning signs can no longer be ignored.

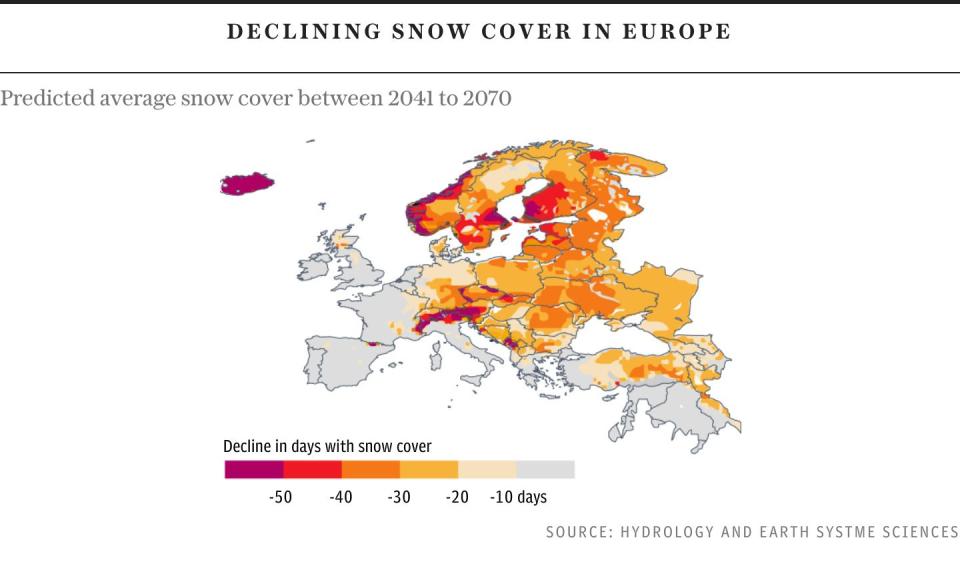

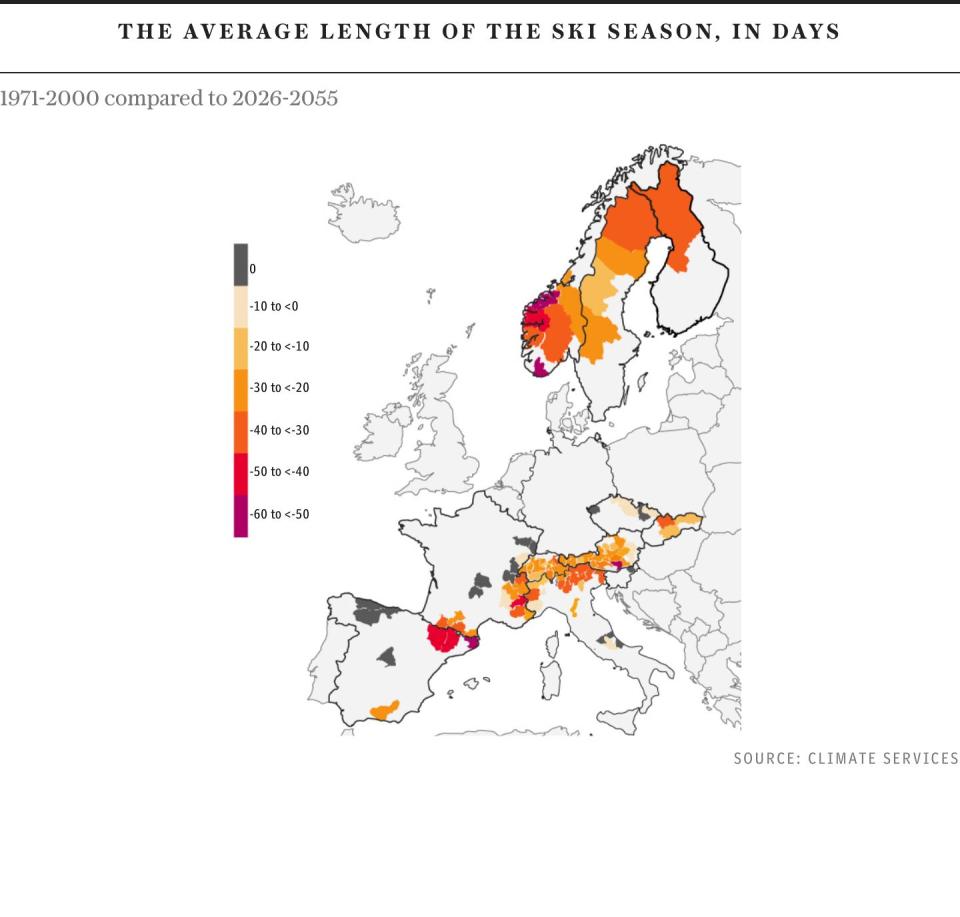

While global temperatures have risen by around 1C, in the Alps that increase has doubled — to 2C. The ski season is now a month shorter than in the 1970s, with white Christmases becoming a thing of the past and the snowline — the altitude at which rain turns to snow — rising catastrophically fast.

The headlines just keep coming. Flash floods in St Anton am Arlberg in August were followed by news in September that the border between Italy and Switzerland, around the Matterhorn, was being re-drawn due to glacial melt.

Last week, shock headlines that European ski resorts risked being “wiped out within decades” were sparked by the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) and the International Ski and Snowboard Federation (FIS) – the governing body for ski and snowboard competition – joining forces to tell the world that winter sports and tourism face “a bleak future”.

Johan Eliasch, FIS president, described climate change as “an existential threat to skiing and snowboarding”.

How bad could things get, and how fast?

Despite recent headlines, the future remains uncertain.

“We saw very high temperatures last year and expect them to continue — the world is warming at an unprecedented rate — 0.26C per decade and as we understand it, these increases will be exacerbated at higher altitudes,” says climate scientist Prof Piers Forster, a lead author on the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), chair of the UK Climate Change Committee and director of the Priestley International Centre for Climate at the University of Leeds.

Prof Forster is not only a leading climate scientist, but also a keen skier. “Glacial changes and country borders affect me personally because I love ski touring and these high-altitude Alpine huts and climbing routes are changing and becoming more dangerous,” he says.

Climate change in the mountains is not just about the amount of snow left to ski on though. Changing temperatures, retreating glaciers, reduced snow and ice cover, and thawing of permafrost (ground that remains continuously frozen for two years or more) are impacting mountain ecosystems, communities and entire economies.

“As skiers, we have front row seats — but most don’t know the consequence of what we see visually [lack of snow]. Everything is under threat and it goes far beyond resorts shutting in 2025,” says Chemmy Alcott, TV presenter, former British Olympic skier and ambassador for Protect Our Winters UK.

Lift networks are at risk as permafrost thaws and previously stable ground begins to move, impacting resort infrastructure from transport systems to mountain huts and restaurants. A 2021 study by scientists at the University of Grenoble and the University of Savoie Mont Blanc, referenced in the latest IPCC report, identified 947 infrastructure elements – for example, a lift pylon – likely to be affected by changes to the permafrost in France alone. 84 per cent of these are at low-to-medium risk and 16 per cent are at high risk of destabilisation. The scientists behind the study have called for the research work to be urgently extended to the whole Alps, but said to their knowledge, this has not yet begun.

Where is most at risk?

Undeniably, ski resorts below 1,500m in altitude have little future in snow sports. The WMO warned last week that the zero-degree level (the altitude at which temperatures allow lasting snow cover) will hit 1,500m by 2060 — compared with around 850m above sea level today. Snow cannons are of course important, but they come with an environmental and economic cost and rely on cold temperatures to work.

Already more than 180 small ski areas in France have closed since the 1970s, due to lack of snow. The latest casualty is Seyne-les-Alps, where this week locals voted to close their ski area permanently, following a halving in visitor numbers due to the regular absence of snow. The town had taken out a €2 million loan to run and maintain the lifts, but is now looking at alternative sources of revenue.

Ski resorts have been modelling best and worst-case scenarios to prepare themselves for the decades to come, and responding by moving their infrastructure accordingly. Val d’Isere – one of the most popular ski resorts with British holidaymakers – created a nursery slope area at the top of its Solaise mountain in 2016 and, last winter, La Plagne moved the route of its Les Glacier lift and top station off the Bellecote glacier to an area of more stability.

Lower resorts still in operation are urgently working to attract tourists all year round — by, for example, investing in mountain biking and hiking trails for summer — to spread their economic viability.

In January, Christine Ferrière, deputy manager of Savoie Mont Blanc, told The Telegraph: “It’s a different future ahead. These resorts know it and have started thinking about how to diversify, they know the income won’t be as high as it is today.”

But it’s not all about altitude. Location also plays a strong part in weather and snowfall in mountain areas. The SkiWelt area in the Tyrol is one of the most reliable for snow conditions in Austria, despite the fact that all six of its resorts — including Söll (700m) and Ellmau (800m) – are under 1,000m in altitude.

SkiWelt marketing manager Anita Baumgarner said: “We are on the northern side of the Alps, like St Anton in the Arlberg, so even though we are very low, when the weather comes from the north we get rain in the summer or snow in the winter, so this is the main thing – elevation isn’t the most important here, like it is in the central Alps.”

How will ski holidays change?

Ski holidays and skier habits are already changing. Tour operators report an increased number of last-minute bookings, with people waiting for snowfall before travelling, while high-altitude resorts are becoming busier and increasing their prices.

Rob Dixon from SkiWorld said: “The prices in Val Thorens (2,300m) – the highest resort in Europe – are now eye-watering, over £2,000pp for a week in a three-star apartment in February half term. The accommodation quality is not anywhere near as nice as you can get in Méribel (1,450m), and we’ve asked the tourist board in Val Thorens to feed it back to the industry that prices are too high, but people are queuing up to stay there.”

Ski resorts are beginning to weatherproof their offerings in other ways. Aspen, Colorado, offers in-resort credit for unused days on lift tickets, which can be transferred between guests and used against future lift passes, lessons, activities or equipment rental. In the Haute Maurienne Vanoise in France, skiers can buy a “weather guarantee” insurance (between 8 per cent and 12 per cent of the cost of the lift pass), entitling them to a refund of the cost of the day’s skiing if it rains for more than three hours, between 9am and 5pm.

Injury rates are also on the up, among both professional ski racing and recreational skiers. “There’s a big correlation between injuries and climate change,” said Alcott. “On race pistes now, more than 50 per cent of snow is injected, which is just brutal ice that you cannot train on. Technicians change ski edges to an angle athletes are not used to. We saw far more ACL injuries last year — they are going up astronomically.”

Jonathan Bell, a knee surgeon at the Fortius Clinic in Wimbledon, said: “We used to quote an injury study from Norway as a baseline figure that for every 10,000 lift rides one skier will be injured. But a study from Colorado a few years ago said ski injuries were more likely to occur on warmer days (14 per cent higher) than on cold days and there was a whopping 81 per cent increase in injuries on hard-packed snow, compared with on a powder day.”

Skiers should expect shorter seasons too – scientists predicted that in 2050 the ski season will be between 14 days shorter (best-case scenario) or as much as 62 days, if global emissions continue to rise – and expect more resorts to implement measures to control the number of people on the pistes – a practice is successfully applied across parts of the US, Canada and in Japan.

“As we continue to grow our base of Epic Pass Holders, we are simultaneously focused on preserving the on-mountain experience – limiting ticket sales is a lever we can pull to help us manage the experience during the most popular times,” said a spokesman for Vail Resorts, which owns and operates 42 mountain resorts around the world.

“The Alpine industry just has to prepare. We don’t all want to go to La Plagne and ski on one bit of snow, it will be a horrible experience,” said Prof Forster. “We need to think about cross-country skiing through woodland, about alpine walking. There are still things you can do and enjoy in the mountains in winter.

“We are still going to get some very cold winter days and good dumps of snow, but what has occurred is the weather has become more unstable and we get these alpine heatwaves, where the whole snowpack can almost disappear.”

The bottom line is that skiers need to limit their impact on climate change and adapt their behaviour and expectations accordingly, believes Nicolas Hale-Woods, founder of the Freeride World Tour, which has been weather-affected in recent years. “You can still have fun in average conditions — it’s part of life’s values to adapt and make the most of what we have,” he said.