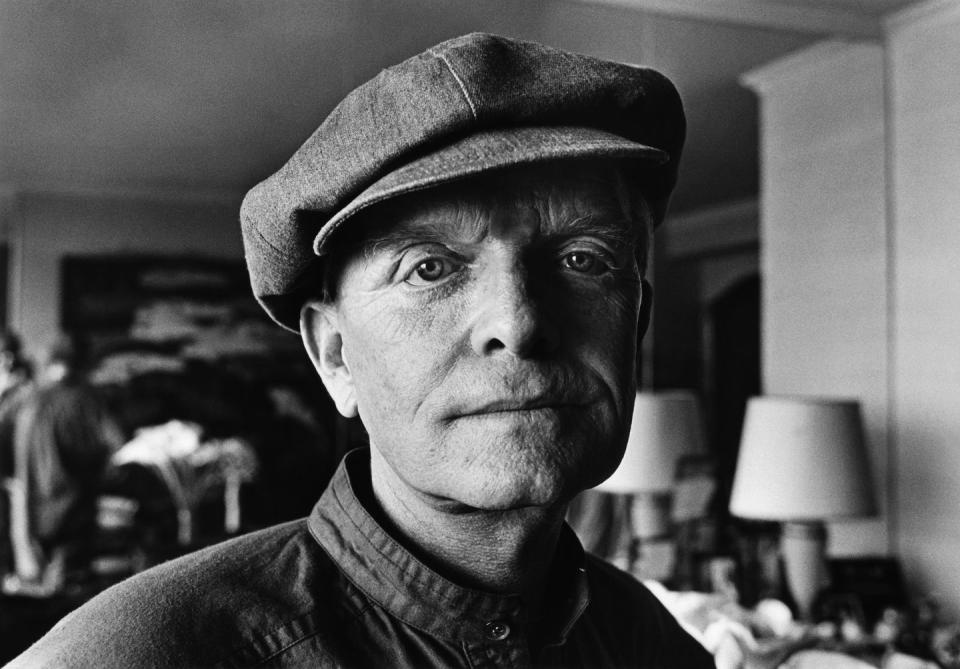

Truman Capote's Final Days: The True Story of the Author's Untimely Death

Truman Capote’s death in 1984 didn’t come as a shock, even at the age of 59. The acclaimed author of Breakfast at Tiffany’s and In Cold Blood spent the decade preceding his demise publicly sliding into addiction, frequently while appearing on talk shows. And as FX’s limited series Feud: Capote vs. The Swans shows, the process of what many dubbed Capote’s slow suicide was as painful as it was prolonged.

The beginning of Capote’s end is generally agreed to have started with the publication of “La Côte Basque, 1965” in 1975. Shunned by the friends he betrayed in the short story, Capote combined coasting on the success of In Cold Blood with an aimlessness that found him choosing inappropriate partners and indulging in drugs and alcohol to a self-sabotaging degree. By the time he died, his reputation was so tarnished that the New York Times’ obituary only waited until the fourth paragraph to write that, according to his critics, Capote “failed to join the ranks of the truly great American writers because he squandered his time, talent and health on the pursuit of celebrity, riches and pleasure.”

But despite Capote’s very public flameout, he didn’t spend 10 years shuttling in and out of rehabs and Studio 54. Feud made his performance in the 1976 Neil Simon comedy spoof Murder by Death into a byproduct of his debilitating addiction, but that movie has become a cult classic—despite Capote’s performance, perhaps, but certainly more beloved and screened than Capote’s Laura, starring Lee Radziwill. But more importantly, Capote kept writing.

In the 19 years between the publication of In Cold Blood and his death, Capote published only one book of original material. That book, Music for Chameleons, is often ignored in the tragedy of Capote’s final years, but it was certainly noticed upon publication in 1980, spending 16 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list. Capote wrote most of the book in 1979 as a contributor to Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine, under the editorial hand of Brigid Berlin. The collection's longest story was the true crime account “Handcarved Coffins,” an eerie story involving miniature coffins and a rattlesnake left in a car that is as effortlessly enthralling as In Cold Blood. But despite writing the short story “One Christmas” and an ode to the late Tennessee Williams, by 1983, Capote was suffering hallucinations and turned increasingly reclusive, spending most of his final year with Joanne Carson in the guest room of her Bel Air home.

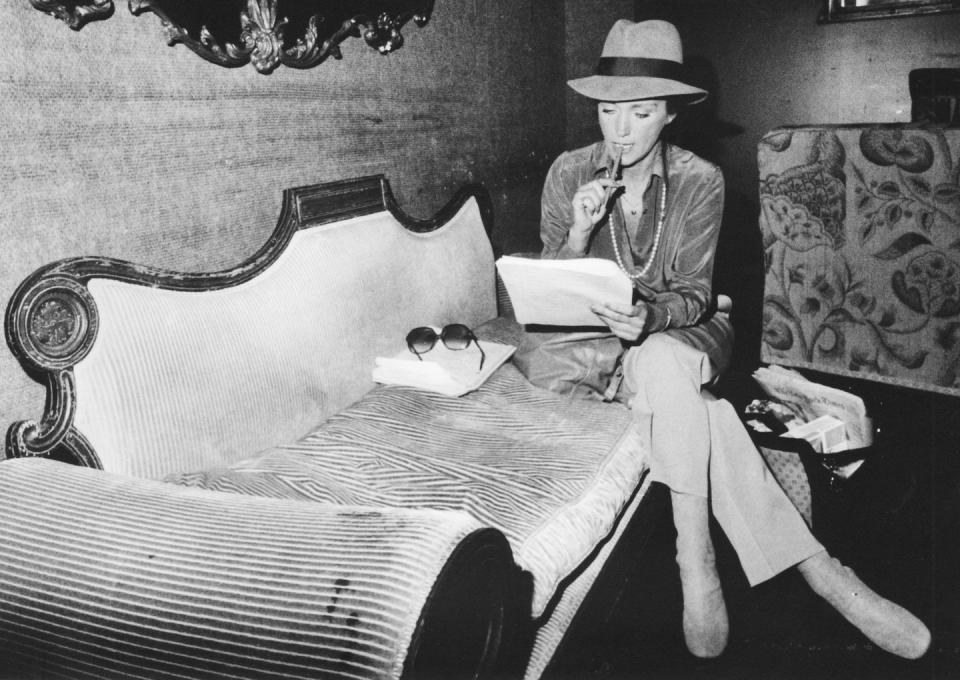

Carson ultimately made something of a late-in-life career out of being the last one with Capote, speaking in interviews about the fate of Answered Prayers (the finished chapters “will be found when they want to be found,” she claimed Capote told her) and keeping his ashes in the bedroom where he died. Technically, half his ashes. Carson said that she was following Capote’s instructions, splitting his ashes into two urns and giving one to his partner, Jack Dunphy. She neglected to mention she kept an urn herself, and when Dunphy found out, he never spoke to her again.

Carson later claimed that someone stole Capote’s ashes during a Halloween party at her house (she “recovered” them, allegedly finding them in her garden hose) and had half of them interred next to Marilyn Monroe in Westwood Village Memorial Park. The remaining quarter of Capote’s ashes stayed with Carson until her death in 2015, after which they were auctioned off for $45,000.

One of Capote’s most brilliant attributes as a writer was admiring and paying deference to the telling detail. His eye is what makes In Cold Blood so chilling, what makes Breakfast at Tiffany’s so alluring, what makes his profile of Marlon Brando so deadly. So one hopes he would find mordant appreciation in the postscript of his public life, where his ashes were just one lot in an auction that also found people bidding on a lock of Marilyn Monroe’s hair, a batch of Steve Jobs’ neckties, and a shirt from The Dukes of Hazzard.

You Might Also Like