Tower Bridge and other landmarks that almost looked completely different

Rejected designs that reveal what might have been

Photocreo/Michal Bednarek/Shutterstock

Did you know the Arc de Triomphe almost looked like a giant elephant? From Paris to the Potomac River, some of the world's most famous places could have looked very different if these alternative plans for iconic landmarks and buildings had been given the green light.

Read on to discover how 25 beloved buildings, including the Eiffel Tower, Washington Monument, and Sydney Opera House, might have turned out...

All dollar amounts in US dollars

Selfridges, London, England

BasPhoto/Shutterstock

Luxury London department store Selfridges was designed by architect Daniel Burnham for American retailer Harry Gordon Selfridge and opened its doors to the public in 1909. The second-largest retail space in the UK, Selfridges is known all around the world.

But the original design could have been even more iconic...

Selfridges, London, England

Courtesy RIBA Collections

An imposing, comically implausible 450-foot tower was proposed for the department store in 1918 by architect Philip Armstrong Tilden. Harry Gordon Selfridge reportedly lobbied the local council for years to grant him planning permission for the tower before eventually losing interest.

Eiffel Tower, Paris

WDG Photo/Shutterstock

Practically synonymous with France itself, Paris' emblematic Eiffel Tower was commissioned for the 1889 World's Fair on the Champs de Mars to mark the centenary of the French Revolution. But it wasn't the only contender for the site in central Paris.

Eiffel Tower, Paris

PD-1923/BnF

An open competition was held in 1886 to create the main draw for the fair, and the iron lattice tower was just one of several entries. Astonishingly, a seriously macabre giant guillotine was also proposed.

Thankfully, the competition organisers eventually opted for Gustav Eiffel's design.

Washington Monument, Washington DC, USA

Holbox/Shutterstock

The Washington Monument is one of the American capital's star attractions, but the obelisk you see today is actually a watered-down, cheaper version of the original plan devised by architect Robert Mills in 1845.

Washington Monument, Washington DC, USA

PD-1923/Wikimedia Commons

Mills envisaged a Neoclassical columned temple at the base of the obelisk, topped by an ostentatious statue of George Washington in a chariot. The society in charge of erecting the monument baulked at the price tag and, in the end, chose to build just the obelisk.

Lincoln Memorial, Washington DC, USA

Jiawangkun/Shutterstock

While Washington missed out, America's monument to Abraham Lincoln does take the form of a Greek Doric temple, complete with columns and classical sculptures. Completed in 1922, the Washington DC memorial was designed by architect Henry Bacon.

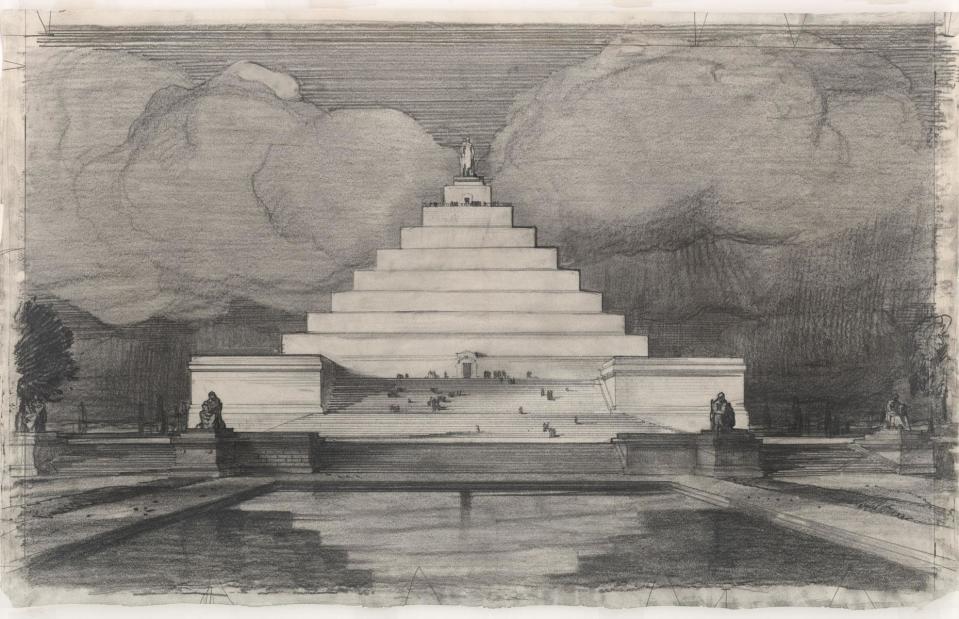

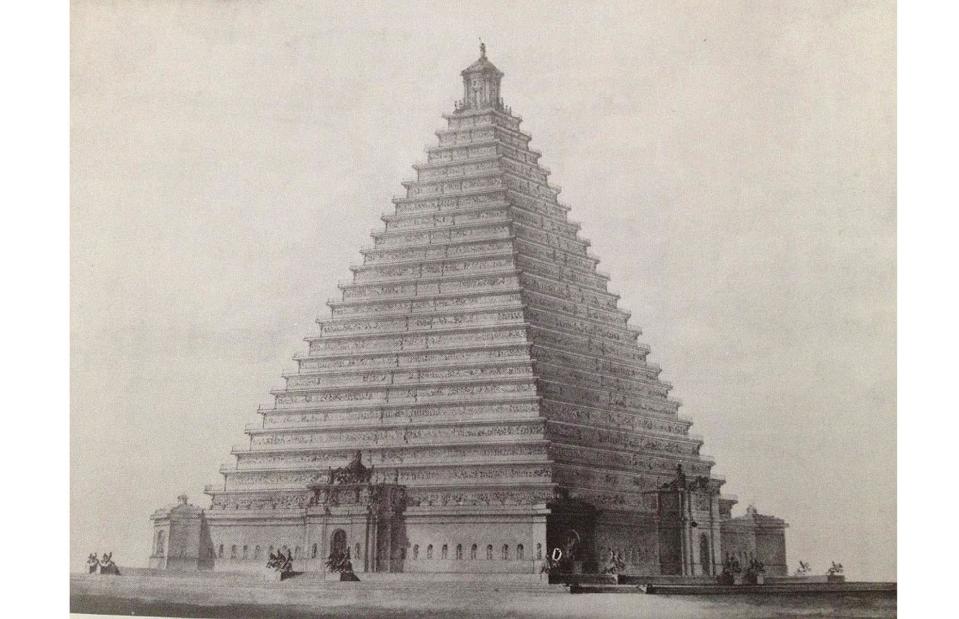

Lincoln Memorial, Washington DC, USA

Courtesy National Archives

However, several competing designs were in the running, including a simple log cabin, an Egyptian-style pyramid, and a ziggurat designed by John Russell Pope.

Tower Bridge, London, England

Photocreo/Michal Bednarek/Shutterstock

A competition to design a crossing over the Thames downstream from London Bridge was launched in 1876, and the winning bascule (moving) design we're familiar with today was commissioned in 1885.

Tower Bridge, London, England

PD-1923/Engineer magazine

Over 50 designs were considered by the judges, who stipulated the bridge must allow tall ships to pass beneath. Among the most notable, apart from the winner of course, are these three high bridge designs by the great architect and engineer Joseph Bazalgette.

Sydney Harbour Bridge, Australia

Taras Vyshnya/Shutterstock

Nicknamed "The Coat Hanger", Sydney Harbour Bridge is arguably the city's second-most recognisable structure after the Sydney Opera House. The steel arch bridge, which opened to the public in 1932, was designed and built by British engineering firm Dorman Long.

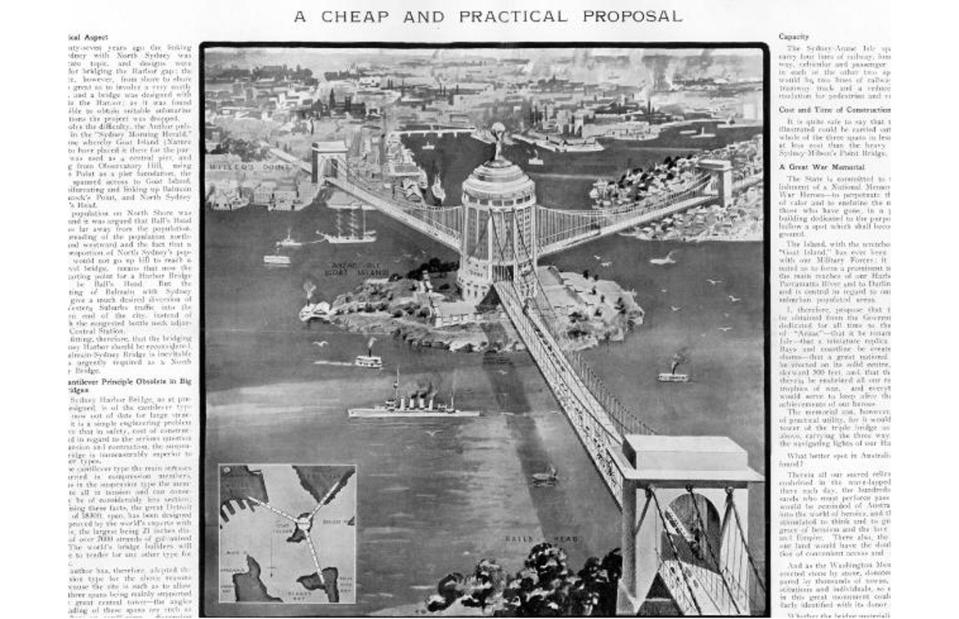

Sydney Harbour Bridge, Australia

Courtesy National Archives of Australia

Plans to build a bridge in the harbour had been floated as early as 1815, and plenty of designs had been proposed in the years before Dorman Long's structure won the day. Among the most interesting is this striking multi-way bridge, submitted for consideration in 1922 by architect Ernest Stowe.

Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral, England

Yuriy Chertok/Shutterstock

Liverpool's Metropolitan Cathedral may have garnered icon status. However, the modern Catholic cathedral, which has been described as a cheap take on Oscar Neimeyer's Cathedral of Brasilia, has been beset by structural problems since construction began in 1962.

The building's issues got so bad that the Catholic Church sued the architect, Frederick Gibberd.

Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral, England

Peter Byrne/PA Archive

Years earlier, renowned English architect Edwin Lutyens proposed something much more ambitious. His design boasted the largest dome on the planet and would have been the world's second-largest church if realised. Work began on the building in 1933, but skyrocketing costs and World War II halted construction in 1941. The project was eventually abandoned.

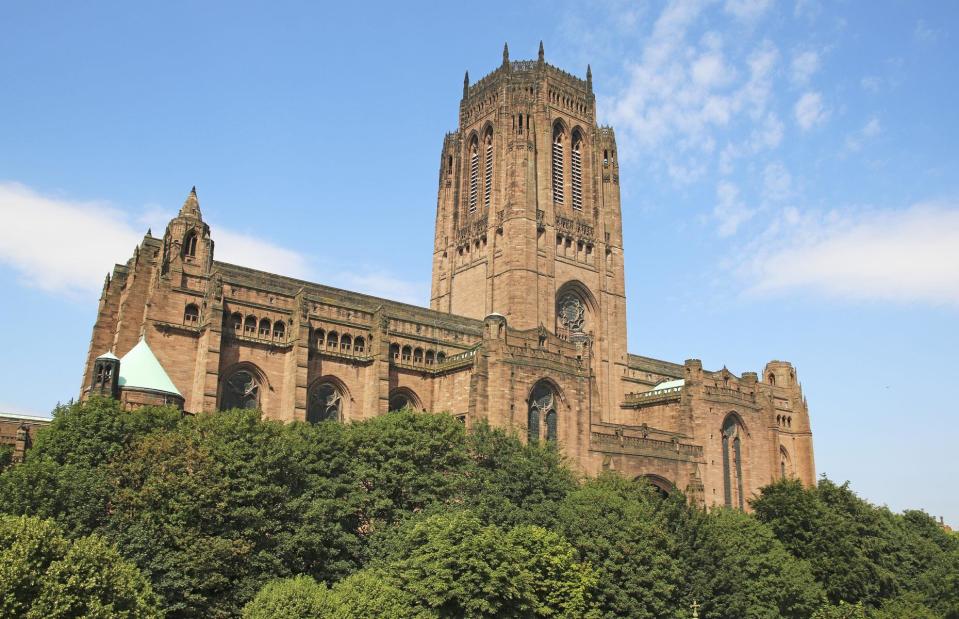

Liverpool Cathedral, England

Alastair Wallace/Shutterstock

Liverpool's Anglican Cathedral was designed by Giles Gilbert Scott, who's noted for blending neo-Gothic with a modern aesthetic. Construction began on the Church of England cathedral in 1904, but the building wasn't completed until 1978.

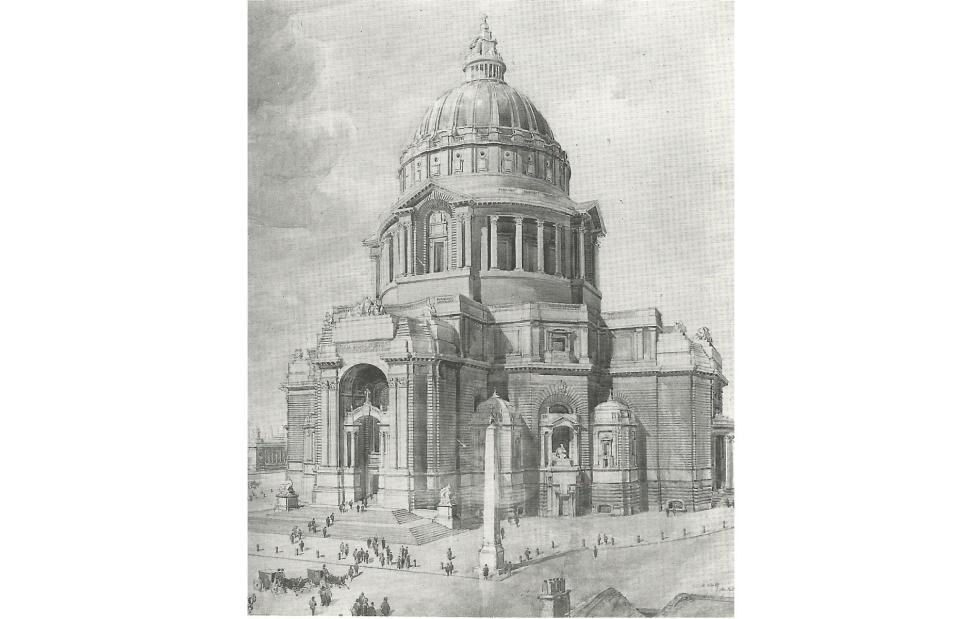

Liverpool Cathedral, England

PD-1923/Wikimedia Commons

Scott won the open competition to design the cathedral in 1903. A number of outstanding entries were proposed, including this Neoclassical design by Charles Herbert Reilly, which nods to St Paul's Cathedral in London.

Arc de Triomphe, Paris

Frederic Prochasson/Shutterstock

The Arc de Triomphe, which takes pride of place at the top of the Champs-Elysées in Paris, is almost as iconic as the Eiffel Tower. The grandiose arch was erected in 1806 to honour those who had fallen in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.

Arc de Triomphe, Paris

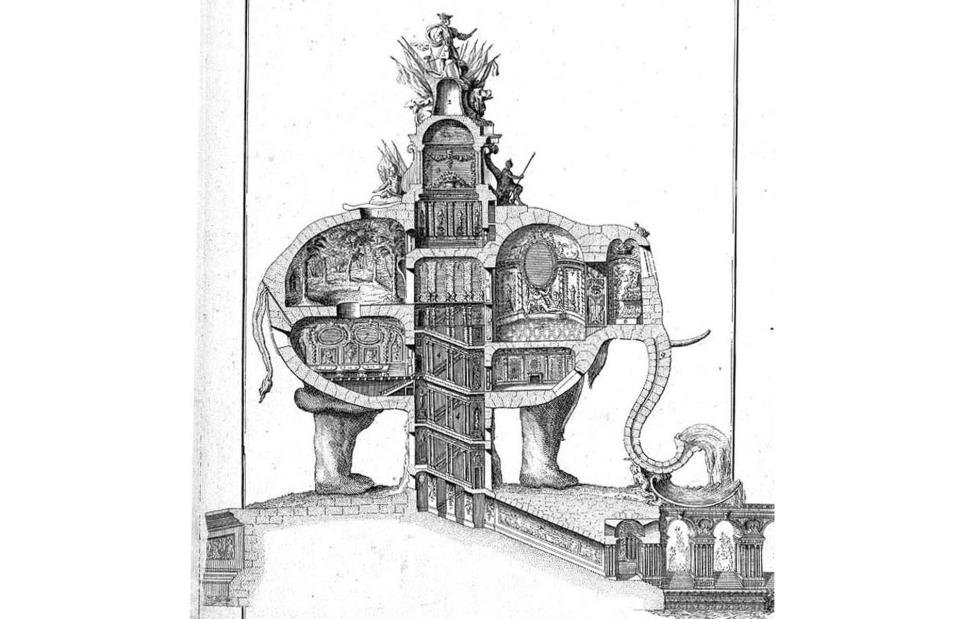

Nunh-huh/Wikimedia Commons

Bizarrely, a grand elephant-shaped building was initially proposed for the site on which the Arc de Triomphe stands today. Architect Charles Ribart planned the three-level structure in 1758, complete with primitive air con and foldaway furniture, but the authorities turned down his wacky design.

Palace of Westminster, London, England

Samot/Shutterstock

The old Houses of Parliament in England were destroyed by fire in 1834, and a competition was launched soon after to design a replacement. Ultimately, the judges selected Charles Barry's Gothic Revival masterpiece, and the structure was completed in 1870.

Palace of Westminster, London, England

Courtesy RIBA Collections

A total of 97 entries were received in the competition to design the replacement parliament building, including this spectacular Neoclassical palace by visionary architect Joseph Gandy, which would have been located in London's St James's Park.

Chicago Tribune Tower, USA

Steve Cukrov/Shutterstock

One of Chicago's most admired and well-known buildings, the resplendent neo-Gothic Tribune Tower soars into the Windy City sky like an ancient supersized cathedral. The ornate skyscraper, completed in 1925, is the handiwork of New York-based architects Raymond Hood and John Mead Howells.

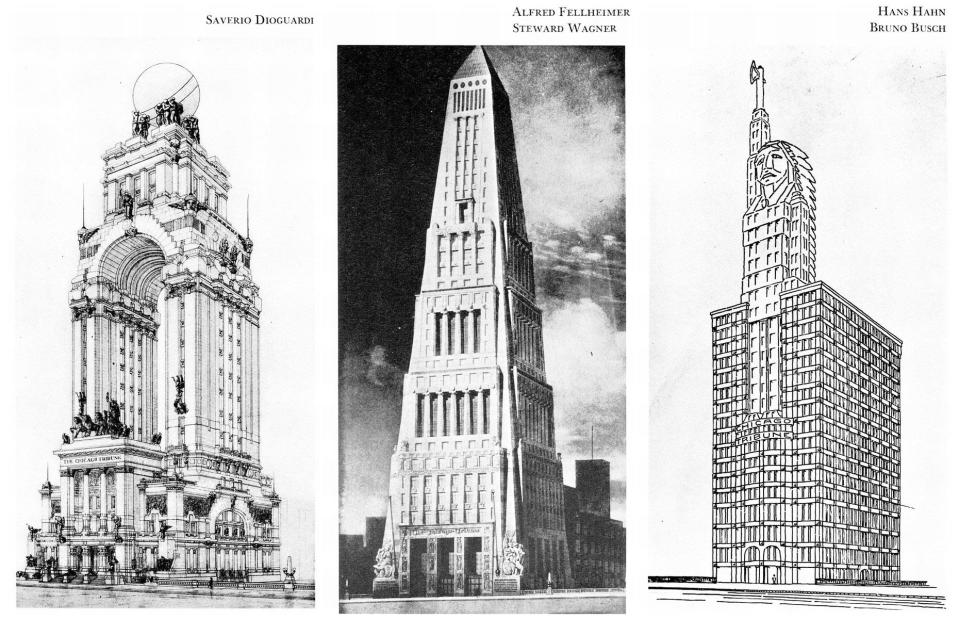

Chicago Tribune Tower, USA

PD-1923/Chicago Tribune archive

Hood and Howells' neo-gothic design was one of 259 entries in an international competition launched in 1922 to create a new HQ for the Chicago Tribune newspaper. Some of the more outlandish entries included an arched building crowned by a globe, an Art Deco pyramid, and a skyscraper featuring the head of a Native American chief.

Royal Courts of Justice, London, England

Patrick Wang/Shutterstock

London's Royal Courts of Justice building, opened by Queen Victoria in 1882, was designed by George Edmund Street, one of the leading figures in the Victorian Gothic Revival movement, hence the medieval cathedral-like turrets and church-inspired windows.

Royal Courts of Justice, London, England

PD-1923/Alfred Waterhouse

Street beat 11 architects to win the competition to design the building, including fellow Gothic Revival exponent Alfred Waterhouse. He proposed an even grander edifice with several tall towers, elements of which survive in his masterpiece, London's Natural History Museum.

Golden Gate Bridge, San Francisco, USA

Somchaij/Shutterstock

One of the most famous and beautiful suspension bridges on the planet, San Francisco's glorious Golden Gate Bridge opened to traffic in 1934. The 1.7-mile-long crossing, which has been declared a Wonder of the Modern World, was designed by engineer Joseph Strauss.

Golden Gate Bridge, San Francisco, USA

Courtesy California Historical Society

Strauss actually had a different design in mind before he went with the clean suspension bridge San Franciscans know and love today. The original plan was for a bizarre hybrid suspension and cantilever bridge that lacks the exquisite simplicity of Strauss' final design.

St Paul's Cathedral, London, England

Shutterstock

Christopher Wren's majestic St Paul's Cathedral rose from the ashes of the Great Fire of London in the late 17th century and has been one of the city's most celebrated landmarks for centuries. The massive dome, the second-largest cathedral dome in the world, is its defining characteristic.

St Paul's Cathedral, London, England

PD-1923/All Souls College, Oxford

The enormous rounded dome design may not have seen the light of day, though, had the powers that be plumped for the so-called Warrant design. This early proposal features a smaller, more modest dome and has none of the "wow" factor of Wren's final draft.

United States Capitol, Washington DC, USA

Lyubov Timofeyeva/Shutterstock

The United States Capitol in Washington DC is also famous for its massive dome, which is actually made of cast iron rather than stone. The building is the product of a design competition set by the then-Secretary of State, Thomas Jefferson, in 1792 and judged by President George Washington.

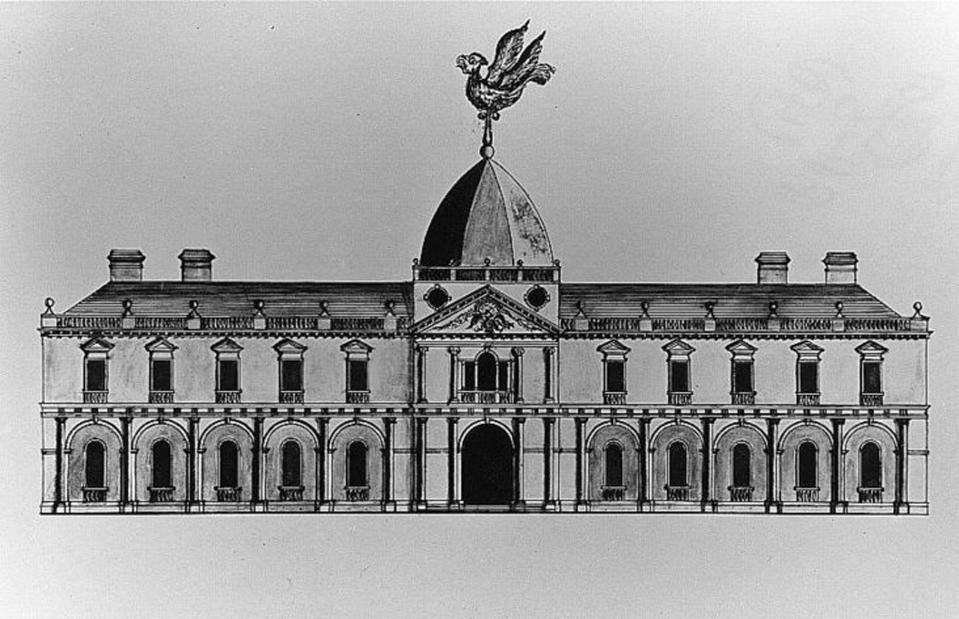

United States Capitol, Washington DC, USA

Courtesy Maryland Historical Society/Library of Congress

The dome was a later addition to the winning entry designed by architect William Thornton. Fortunately, Jefferson passed on this entry by amateur James Diamond, which features an eagle weather vane resembling a giant chicken.

The White House, Washington DC, USA

Turtix/Shutterstock

Proposals for a new "President's House" were also submitted to Jefferson's design competition. Irish-born architect James Hoban got the gig, and the sophisticated mansion was eventually completed in 1800.

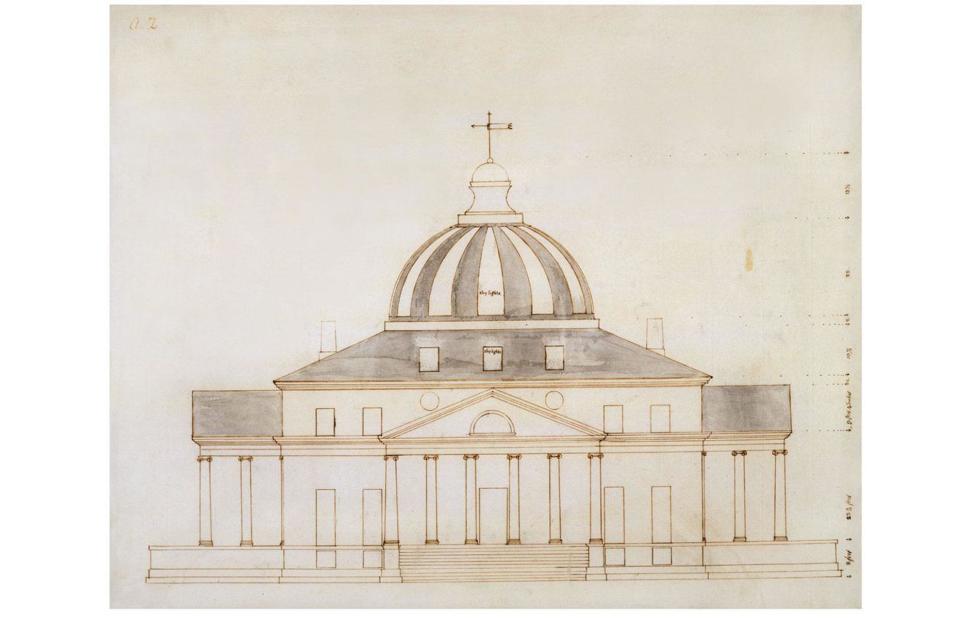

The White House, Washington DC, USA

Courtesy Maryland Historical Society

But the White House might very well have looked like this. The domed design, which is said to have been submitted anonymously by Jefferson via Virginia builder John Collins, was admired by Washington and nabbed second place in the competition.

Arlington Memorial Bridge, Washington DC, USA

Daisy Dee/Wikimedia Commons

Staying in DC, a crossing over the Potomac River to memorialise America's fallen was in the pipeline for decades before Congress finally approved the Neoclassical bridge by architectural firm McKim, Mead, and White. The Arlington Memorial Bridge was completed in 1932.

Arlington Memorial Bridge, Washington DC, USA

Courtesy National Building Museum

This more distinctive neo-Gothic design was proposed by architect Paul J. Pelz in 1887 as a homage to General Ulysses S. Grant. Congress wasn't too keen on facilitating a memorial to Grant and blocked funding of the original design, eventually giving the all-clear for the Neoclassical bridge years later.

Trafalgar Square, London, England

Anton Balazh/Shutterstock

London's iconic Trafalgar Square is famed for its centrepiece, Nelson's Column, not to mention the lion sculptures and statues of several illustrious figures. The square, which commemorates the Battle of Trafalgar of 1805, was opened to the public in 1844.

Trafalgar Square, London, England

Courtesy The Royal Library

The sprawling square could have been a 300-foot-high pyramid if "the Grand Old Duke of York", Prince Frederick, had his way. In 1815, the royal was behind a scheme to build the huge pyramid on the land that would later become Trafalgar Square. However, the hefty price tag – $1.2 million (£920k) at the time – proved prohibitive.

Nelson's Column, London, England

Tony Baggett/Shutterstock

The main focal point of Trafalgar Square might have looked very different too. In 1838, a competition was held to design a fitting memorial to England's greatest admiral, Lord Nelson, and William Railton's Corinthian column was eventually selected.

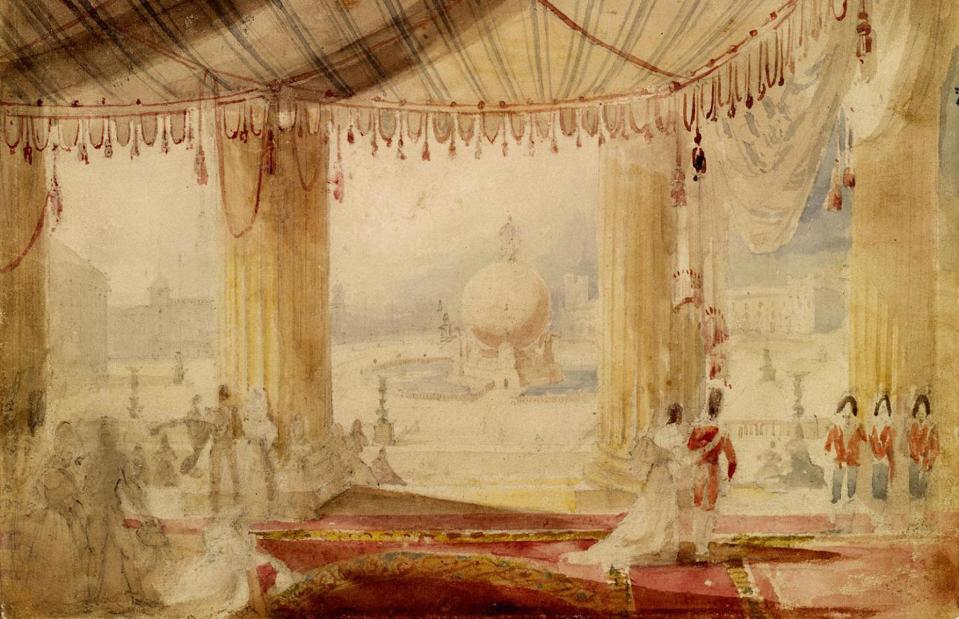

Nelson's Column, London, England

Courtesy RIBA Collections

Among the entries was this elegant globe sculpture, which would have been surrounded by a water feature. The design by architect John Goldicott was revealed in this 1841 watercolour painting but didn't impress the judges as much as Railton's column.

Grand Central Terminal, New York, USA

TTstudio/Shutterstock

A number of architectural firms vied to conceive New York's Grand Central Terminal in 1903, and the contract to design the station was awarded to two firms, Reed & Stem and Warren & Wetmore.

Grand Central Terminal, New York, USA

PD-1923/McKim Mead & White

The stunning Beaux-Arts station, famous for its cavernous hall, is one of the Big Apple's most esteemed landmarks. But it could well have been a neo-Gothic palace, complete with a 60-storey tower, if this proposal by McKim, Mead & White had won the competition.

Tate Modern, London, England

Bikeworldtravel/Shutterstock

The disused power station turned modern art gallery is one of the most successful repurposing projects on the planet. Architectural firm Herzog & de Meuron won the 1994 competition to design the conversion.

Tate Modern, London, England

Courtesy David Chipperfield Architects

The former Bankside Power Station would have lost its characteristic brick tower if this design by David Chipperfield Architects had been selected. The design was one of six shortlisted by the Tate trustees.

Parliament House, Sydney, Australia

JBar/Wikimedia Commons

Sydney's Parliament House, the oldest public building in the Australian city, dates back to the early 19th century. The government building is modest and unexceptional, unlike the parliamentary buildings in other Australian cities, such as Melbourne, which are far more grand.

Parliament House, Sydney, Australia

Courtesy NSW Government

Sydney could well have given Melbourne's splendid Parliament House a run for its money if this design by Irish architect William H. Lynn had come to fruition. Lynn won a competition launched in 1861 to redesign the Sydney building, but funds dried up and his neo-Gothic design was never built.

Library of Congress, Washington DC, USA

Brian Pirwin/Shutterstock

Architect Paul J. Pelz's design for the Library of Congress, since renamed the Thomas Jefferson Building, ultimately prevailed, but several plans were considered for the building following a competition in 1873.

Library of Congress, Washington DC, USA

Courtesy Library of Congress

More like a cathedral than a civic building, this neo-Gothic design was also in the running, as was a ridiculously palatial Beaux-Arts design. Pelz's winning entry boasts a similar Beaux-Arts style but is far less fussy and embellished.

Chrysler Building, New York, USA

Andrew Lichtenstein/Corbis via Getty Images

Arguably the most beautiful skyscraper in the world, the magnificent Chrysler Building in Manhattan is an Art Deco masterpiece adored by New Yorkers and visitors to the city alike. The iconic building was designed by William Van Alen and completed in 1931.

Chrysler Building, New York, USA

Courtesy William Van Alen/Chrysler Corporation

This fascinating series of images shows how the design of the skyscraper was developed and refined by Van Alen. The New York-based architect came up with several designs for the crown of the building before settling for the terraced design we know today.

Sydney Opera House, Australia

Chris Howey/Shutterstock

When you think of Sydney, Australia, the city's world-famous opera house is likely to spring to mind. Danish architect Jørn Utzon won the international competition to design the building, and the opera house, which evokes the billowing sails of a boat, was completed in 1973.

Sydney Opera House, Australia

Courtesy National Archives of Australia

It's a good thing the judges settled for Utzon's elegant design. This Brutalist offering by American architect Joseph Marzella, which has been likened to a sewage treatment plant, toilet roll, and nuclear power station, bagged second place and might well have won the competition.

Now take a look at some of the world's most amazing unfinished landmarks