Tour the Cold War missile base undisturbed for 40 years

Discover the secrets of this curious Cold War missile base

A_.ndrew / Shutterstock

Built during the early 1970s to protect America from nuclear war, this multibillion-dollar defence complex in remote North Dakota was operational for only a few months before it was shut down and left to deteriorate. Straight out of a sci-fi movie, the abandoned site has drawn plenty of attention over the years thanks to its unusual radar pyramid. Now, the Cold War relic has become an ultra-secure data centre for a crypto-mining company.

Read on to take a tour of the curious site, discover the secrets of its illustrious past and find out more about its transformation...

The Stanley R Mickelsen Safeguard complex

![<p>Troy Larson and Terry Hinnenkamp / Wikimedia Commons [CC0 1.0 DEED]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/10HTxRbp413rnhOBdsCgHw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/e79951ab87855c351840579c122c625f)

Troy Larson and Terry Hinnenkamp / Wikimedia Commons [CC0 1.0 DEED]

Nicknamed “the Pyramid on the Prairie” and “Nixon's Pyramid”, the 431-acre (174ha) Missile Site Radar near Nekoma, North Dakota was part of the Stanley R Mickelsen Safeguard Complex. It was the first site of the US's planned 12-part anti-ballistic missile defence system, known as the Safeguard Program.

The military initiative was announced by President Nixon's administration in 1969 and given the go-ahead by Congress that same year.

Defence at the ready

![<p>National Park Service / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/dkYKHnS8sQb.c8KW6TZhQA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/1b2f09ed173edef5effa22a06eb59cd1)

National Park Service / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]

The goal of the Safeguard Program was to protect America's population centres and Minuteman missile fields at Grand Forks, North Dakota and elsewhere in the event of a nuclear attack by the Soviet Union or China. Radars would detect incoming intercontinental ballistic missiles over the North Pole, which could then be blasted out of the sky before reaching their targets.

This photo shows missiles standing on the complex's launch area – a Spartan missile stands on the right and a Sprint missile on the left.

Staggering cost

![<p>National Park Service / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/Q7Mv8rWUXyzI9BnPLFy.vw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/010d1068a7338f3a74fd75570f5744c9)

National Park Service / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]

Construction began in 1970 and the site was completed in 1975. The entire complex was projected to cost around $5.4 billion at the time, but the estimate didn't factor in additional expenses. According to Snopes, the final bill came in at around $5.7 billion, which translates to a staggering $33 billion (£25bn) today.

Sci-fi structures

![<p>National Park Service / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/iZ_SSqLttZ0qyk.E9mCEcA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/df50f4877366dd399647bafc1713f719)

National Park Service / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]

This photo was taken in 1971 and shows the turret wall of the missile site control building during early construction.

Named after a Commanding General of the US Army's Air Defense Command, the complex consisted of six key components. The Missile Site Radar housed a short-range radar, defensive Sprint and Spartan missiles and computers that would crunch data gathered by the longer-range Perimeter Acquisition Radar. The latter was located on a 270-acre (109ha) site near Cavalier, around 35 miles (56km) to the northeast of the main complex.

Remote Sprint Launch Sites

![<p>National Park Service / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/3O5g32tCq3eIbORVckPT4w--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/bae33982a516699a0433a43869f4b18c)

National Park Service / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]

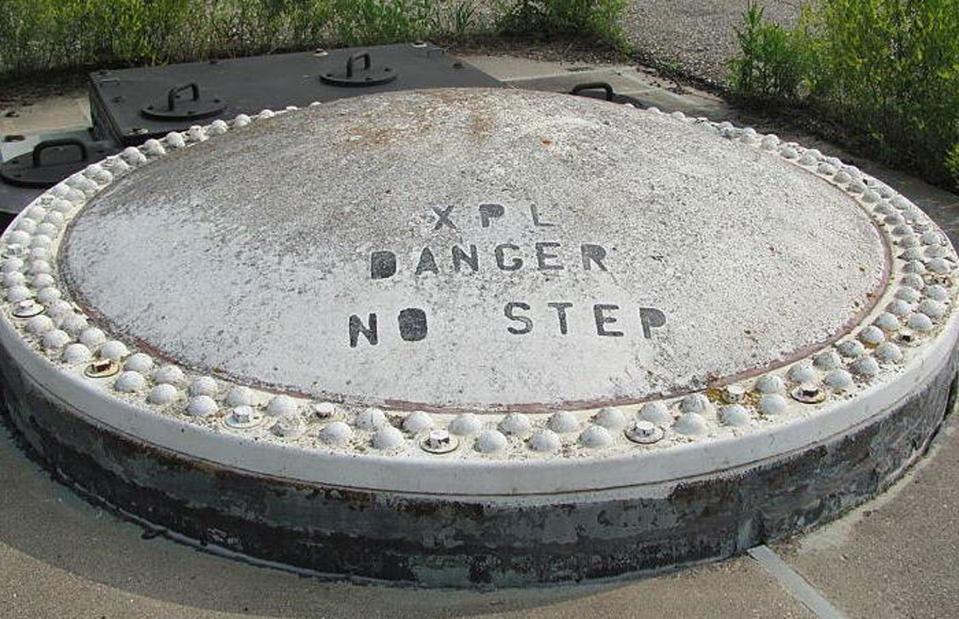

The two radar facilities were complemented by four Remote Sprint Launch Sites, each between 36 and 50 acres (14–20ha) in size. Dotted around the Missile Site Radar at distances of between 10 and 20 miles (16–32km), they each contained a missile field holding 12 to 16 Sprint missiles in launch silos, as well as a sentry station and an underground remote operations bunker encased in reinforced concrete, robust enough to withstand a nuclear detonation in the vicinity.

Changing times

![<p>National Park Service / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/VGUJBhEXaQIiAUWZu_AutA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/663872f6e17cfc358c50dfd5077eccd1)

National Park Service / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]

While the complex was undergoing construction, the US and Soviet Union were engaged in the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT I). The game-changing negotiations resulted in the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty.

The agreement placed a limit on the number of interceptor missiles each country could deploy and restricted both countries to two anti-ballistic missile sites each (and later, just one).

Unceremoniously axed

![<p>Benjamin Halpern / National Park Service / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/K26utm5EnzxStXvb8gR5qg--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/b1cbfd6c2654ddc4116fc27640ce876e)

Benjamin Halpern / National Park Service / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]

In the meantime, the development of missiles with multiple warheads and decoys pretty much rendered the complex obsolete. The system, which was designed to repel single-warhead missiles, would be overwhelmed if nuclear war broke out. And the cost of upgrading it to be fit for purpose would have been astronomical.

Needless to say, the project – which was described as “a system in search of a mission” by its Senate opponents – was on rocky ground, despite the enormous sums of money that had been spent on it. And on 2 October 1975, a day after the complex became fully operational, Congress pulled the plug and ended the Safeguard Program.

A miniature town

![<p>National Park Service / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/SY_zbaC6cVZbfR7mdrw0wQ--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/0f401901ee96ca100584dcf45edae458)

National Park Service / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]

The complex and its facilities, which had opened in April 1975, were up and running for around eight months. During that time, the Missile Site Radar was a hive of activity, with hundreds of military and civilian personnel working there full-time.

High-spec tech

![<p>National Park Service / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/K5JsLfkjJPaYKLfb92CHvA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/dd6cb17024928bfad8c195a420459337)

National Park Service / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]

In addition to the radar control pyramid and silos, the site boasted an underground power plant, administrative buildings, housing units, a community centre, a chapel, a post office, a gym, a bowling alley, a gas station and more.

This photo gives us a sneak peek inside a power plant control room and shows the central monitoring station console in the foreground. While it might looked dated to us today, this was the pinnacle of technology back in the 1970s.

Decommissioned sites

![<p>United States Air Force / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/er3Eld6Wu_ky8tQVbS5Zfg--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/ab71582bdd02ac9581e7209db4431aba)

United States Air Force / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]

Decommissioning began on 10 February 1976. However, the Perimeter Acquisition Radar was reactivated the following year and the site, which is now part of the Cavalier Space Force Station, remains in operation.

The other five components of the Stanley R Mickelsen Safeguard Complex, the Missile Site Radar and the four Remote Sprint Launcher sites, were effectively left to rot.

Missile Site Radar abandoned

![<p>amanderson2 / Flickr [CC BY 2.0 DEED]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/5RUrI60gqQPxFHu0pICM4g--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/893cd5769b07174ff9e96c98916888c3)

amanderson2 / Flickr [CC BY 2.0 DEED]

After the weaponry, computers and so on were removed and the pyramid was stripped down to its concrete exterior and blast-proof fence, the Missile Site Radar was abandoned and all but forgotten.

That is, until 1989 when the discovery of high levels of toxic polychlorinated biphenyls or PCBs – highly carcinogenic chemical compounds – prompted a clean up of the site. Still, maintenance since then has been minimal. Approaching the pyramid today, the facility doesn't look in the best shape.

Dire state of repair

Panther Media GmbH / Alamy Stock Photo

There were attempts to revive the complex in the years that followed. The Cavalier County Job Development Authority first unveiled plans to redevelop the site back in 2006, though these would sit dormant for over a decade.

In 2012, it was announced that the Missile Site Radar and its surrounding land were to be sold via an online General Services Administration auction. The complex was in a dire state of repair by this point.

According to North Dakota newspaper The Jamestown Sun, at the time of the auction, the General Services Administration, which owns the facility, insisted that the successful bidder pay to clean up the site. An estimated 420,000 gallons (1,589,873l) of groundwater had reportedly seeped into the underground missile silos and become contaminated.

Sold to a religious colony

![<p>amanderson2 / Flickr [CC BY 2.0 DEED]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/UBdnbYsKdAO66ODV1s.GOg--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/298a4a2360d32e68772893a4f458161a)

amanderson2 / Flickr [CC BY 2.0 DEED]

The Cavalier County Job Development Authority was unsuccessful in the 2012 auction. The winning bid of $530,000 (£404k) came courtesy of the Spring Creek Hutterite Colony, a farming community belonging to the Christian Anabaptist Hutterite sect. Often compared to the Amish, the sect espouses pacifist beliefs, which is fitting since the pyramid has been called “a monument of peace”, given it was a catalyst for arms control treaties.

Members of the colony soon got to work farming the land. Taking advantage of North Dakota's fertile soils, which are among the richest in the world, they planted soybeans and alfalfa crops in the fields that surround the facility.

Enigmatic landmark

A_.ndrew / Shutterstock

Back to our tour of the site, the vast concrete complex looks especially dramatic at close quarters.

Unsurprisingly, the pyramid and its monolithic ventilation and exhaust stacks have attracted plenty of attention over the years and found themselves cemented in local folklore. Curious passersby are often fascinated by what some have dubbed the "pyramid with an eye" rising amid the remote landscape, causing rumours to swirl concerning the mysterious origins and use of the structures.

Cutting-edge radar

A_.ndrew / Shutterstock

Of course, the real purpose of the site's pyramid-shaped control building is nothing sinister or otherworldly, but that doesn't make the structure any less fascinating. While the interior may be rusty and deserted, the facility was a marvel during its brief heyday.

On the cutting edge of military technology, the super-sophisticated radar boasted over 20,000 antenna elements. The computer processing hub that crunched the data from the radar is said to have been the largest processor in the world at the time, according to Carol Goodman, a consultant for the site's development at the Cavalier County Job Development Authority.

Blast-proof shell

A_.ndrew / Shutterstock

The radar was located on the structure's two underground main floors for extra protection.

The true scale of the facility and its extraordinary engineering becomes apparent in this image. The building's blast-proof shell, which was made from 27,500 pounds (12,474kg) of steel and 714,000 cubic feet (20,218cbm) of concrete, was built to withstand a nuclear war. It's no wonder the facility cost so much to build.

A powerful bargaining chip

A_.ndrew / Shutterstock

Yet there's a strong argument to be made that the complex saved the US taxpayer untold sums of money. The tremendous cost of the facility is said to have impressed and shocked the Soviets. Suddenly, the idea of building 12 anti-ballistic missile defence installations to keep up with the Americans seemed foolish, and the complex proved to be a powerful bargaining chip in the SALT negotiations. The resulting agreement to limit the facilities to one per nation saved the US tens of billions of dollars that otherwise would've been spent on 11 additional installations.

It's also worth pointing out that almost half of the staggering budget of the North Dakota complex was spent on research and development that had myriad useful applications beyond the Safeguard Program and would have been green-lit anyway.

Changing of hands

dedio / Shutterstock

In 2017, the Cavalier County Job Development Authority finally reached an agreement with the Spring Creek Hutterite Colony to purchase the tactical part of the Missile Site Radar, which includes the pyramid, two bunkers, the missile field and underground power plant.

The authority paid $462,900 (£353k), having secured funding of $600,000 (£457k) from the North Dakota Department of Commerce and various other grants.

Original redevelopment plan

dedio / Shutterstock

After harbouring aspirations for the site since 2006, the job agency's plans were finally brought to the table again. These involved transforming the site into a multi-purpose facility featuring a research, development and business park specialising in drone technology, a Cold War history centre and an education and training hub for military, government and civil organisations.

Innovative ideas

Panther Media GmbH / Alamy

The job authority also came up with the idea of turning the pyramid into an extra-secure data centre for online or cloud data storage. They even hired an engineering company in 2012 to carry out a feasibility study, which showed the concept could work.

While pressing ahead with the Cold War museum plan, the agency eventually ditched the drone park and training hub proposals to focus on the data storage concept and attract a tech company to make it happen.

The perfect buyer

A_.ndrew / Shutterstock

The decision to pivot the plans was shrewd. In July 2022, North Dakota Governor Doug Burgum announced that the job agency had found the perfect buyer for the tactical part of the site: Bitzero Blockchain Inc, a cryptocurrency mining firm and data centre developer backed by top investor and Shark Tank star Kevin O'Leary.

Sustainable crypto-mining centre

A_.ndrew / Shutterstock

Bitzero reportedly paid $250,000 (£190k) for the site, which it plans to turn into a highly secure crypto-mining data centre powered by green energy. In simple terms, crypto-mining involves the processing, securing, verification and synchronisation of all transactions relating to cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin, by a large number of computers.

Bitzero promised to funnell the residual heat and carbon dioxide from the facility into greenhouses growing fruits and vegetables all year round, offsetting the centre's carbon footprint. The firm's environmentally conscious plan ties in nicely with North Dakota's aim to be America's first carbon-neutral state by 2030.

Major investment

A_.ndrew / Shutterstock

In fact, Bitzero selected North Dakota as its centre of operations for North America. When it took over the site, the Norway-based company expected to invest $500 million (£381m) in the pyramid data centre project and create up to 50 jobs in the local area once the complex was operational.

It planned to build 200 megawatts of data centres over the following years, along with a graphene battery assembly and distribution hub. According to it's website, Bitzero's North Dakota site has 2.5 of active megawatts as of 2024, with 30 megawatts available and another 100 that could be unlocked with grid updates so it looks like plans are progressing.

A long road ahead

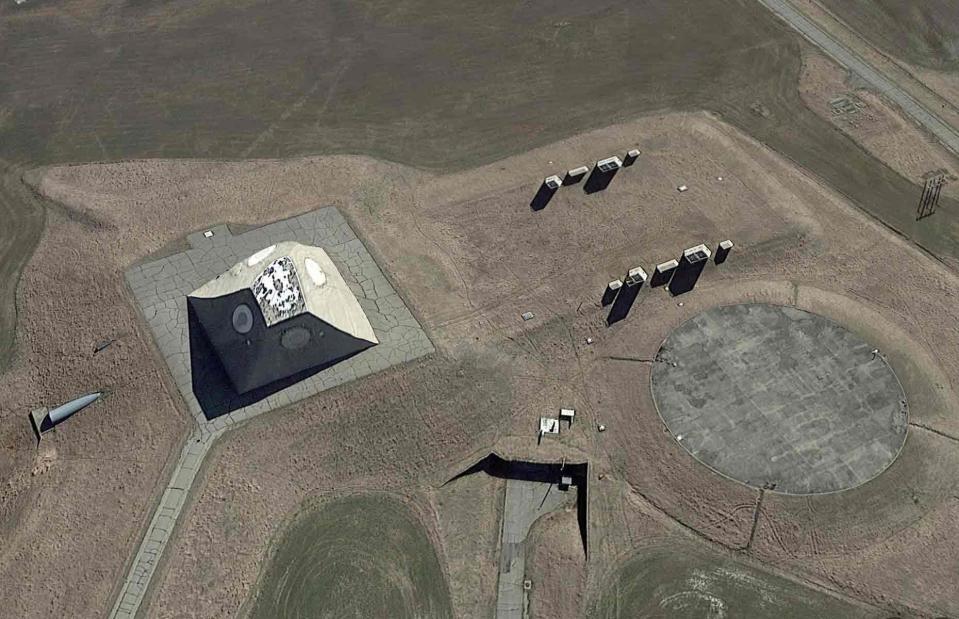

Google Earth

The project required a significant clean-up operation to remove asbestos, repair water damage and carry out other remedial work across the property.

As well as the crucial renovations, the company agreed to build the much-anticipated Cold War museum, which appears to have been a condition of the sale, as well as a few other unexpected amenities. It unclear how many of these plans have come to fruition.

Future tourism hotspot?

A_.ndrew / Shutterstock

Josh Teigen, the then-director of Economic Development and Finance at the North Dakota Department of Commerce, announced in July 2022: "In addition to the historical museum and interpretive center, Bitzero also plans to turn the top floor of the pyramid into an art gallery with sculptures and art from around the world and an executive office suite that will be open to the public on occasion.

"The crowning jewel will be a massive telescope that will be added through one of the former radar’s [sic] in the side of the pyramid. This will truly be a flagship location for the whole world to travel and see."

National Historic Landmark consideration

A_.ndrew / Shutterstock

The icing on the cake came in October 2022 when the National Park Service published a study naming the Missile Site Radar as a property worthy of National Historic Landmark consideration. This has massively increased the site's chances of bagging the accolade, which would guarantee its preservation for generations to come.

The enormous task of overhauling the military site is thought to be currently ongoing.

Selling off the site

Google Street View

Meanwhile, other elements of the historic complex have been sold over the years. The four Remote Sprint Launch Sites were auctioned off by the General Services Administration in 2013 and reportedly purchased by private buyers.

The 41-acre (16ha) RSL-1 went under the hammer for $64,111 (£49k). The buyer wasn't disclosed and the site's fate remains uncertain, though it's thought that the property may have been abandoned.

Remote Sprint Launch Site 2

Courtesy James Cleveland

RSL-2, at 36 acres (14ha) the smallest of the launch sites, was snapped up by Anna and Jim Cleveland for $85,000 (£65k). The couple, who have 13 children, were looking to upsize to an unconventional property spacious enough to accommodate their family. With a generous 14,400 square feet (1,337sqm) of potential living and working space, the former missile installation proved ideal.

An ambitious conversion

Courtesy James Cleveland

The couple's original idea was to convert the 12,000-square-foot (1,114sqm) underground remote launch operations centre into a family home complete with workshop spaces for their business, Frenchman River Model Works, which supplies boat kits to the model railway industry.

The remarkable subterranean bunker features walls 30 inches (76cm) thick, 15-foot-high (4.5m) ceilings and an access tunnel bolstered by mega-tough blast doors.

Home sweet home

Courtesy James Cleveland

As it turned out, the family chose to make their home in the above-ground sentry station, the other main building on the site, and use the bunker strictly for work.

Spanning 2,400 square feet (222sqm), the concrete structure is, like the bunker, designed to withstand a nuclear explosion nearby. Fitted with all mod cons, from AC to propane central heating, the couple transformed the former military outpost into a welcoming family home.

Unique living areas

Courtesy James Cleveland

In terms of rooms, the sentry station consists of a three-car garage, which doubles up as bedrooms and living space, a kitchen kitted out with a reverse osmosis filtration system, a recently remodelled bathroom, an office and the original security desk and turnstile.

Other highlights of the property include the former missile field and two concrete towers.

Missile base for sale

Courtesy James Cleveland

Although the site holds many happy memories – one of the couple's daughters married there, for instance – the Clevelands decided to sell up to be nearer to their adult kids, who have since moved away.

The property was listed in 2018 for $1.5 million (£1.1m), with the asking price reduced to $799,500 (£610k) back in February 2022.

Remote Sprint Launch Site 3

![<p>Halpern, Benjamin / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/UvaUkqUIi3hDhwP1faW.8g--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/c36a2f77db9cc32c1a82fa515908a81f)

Halpern, Benjamin / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]

Meanwhile, Remote Sprint Launch Site 3, which covers 43 acres (17ha), was bought by Melbourne Sann in 2013 for $64,050 (£49k). Sann, who hails from Rome, New York, had wanted to build a bunker under his home for years and jumped at the chance of purchasing the decommissioned nuclear facility.

Sann has spent every summer since he purchased the site doing renovation work there and started offering tours in 2018 to fund the project.

RSL-3 is pictured here in 1992 in an old archive image of the site.

Remote Sprint Launch Site 4

![<p>National Park Service / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/mn9Upnp_iz3UQWAkyH9o5Q--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/b0eb88550595090e992e89902351a03b)

National Park Service / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]

The fourth and final Remote Sprint Launch Site 4 (RSL-4) spans 50 acres (20ha), making it the biggest. This aerial photo shows the site during construction in 1973.

Handyman Leslie Volochenko from Mandan in southern North Dakota outbid five others in 2013 to bag the property for $54,104 (£41k). Volochenko had high hopes of restoring the site, but his plans fell by the wayside and the property was put up for auction at the height of the pandemic in August 2020. The auction sparked a bidding war, with over 70 people taking part. Disappointingly, the top bid was just $52,500 (£40k) and Volochenko, who was planning to use the proceeds to move to Texas, declined the offer.

A new beginning for a Cold War relic

![<p>Troy Larson and Terry Hinnenkamp / Wikimedia Commons [CC0 1.0 DEED]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/djGFA2xFYD94CBFravDngA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/4e2235dbadec0890e6bbc69548b13423)

Troy Larson and Terry Hinnenkamp / Wikimedia Commons [CC0 1.0 DEED]

It's fair to say that the Stanley R Mickelsen Safeguard complex has been through its fair share of turmoil. Despite being effectively shut down a day after its opening, the legacy of this unusual Cold War relic has certainly endured.

Now, as the site finally gets the attention it so badly needs and the pyramid starts a new chapter as a crypto-mining data centre, the future is looking bright for the former military site.