Can sustainability be fun? Montréal thinks so

Frédéric-Back Park was once a dump; a quarry and landfill pit almost the size of Monaco, infested with rats, roaring with waste trucks, belching potent gas, foul with 40 million tonnes of trash. So foul that, in the 1970s, the surrounding residents of Saint-Michel – Montreal’s most ethnically diverse neighbourhood – took to the streets in protest.

But looking around the park today, all is green and serene; the Herculean regeneration project is almost complete. Butterflies sup on meadows of milkweed and echinacea, sunflowers nod in the midsummer heat, new trees push forth, cyclists pedal neat gravel paths. And, err, a fleet of alien spaceships dot the grass…

Olivier Lapierre, who is showing me around, notes my confusion. “The white spheres? They’re wells to capture biogas.”

All that rubbish, now rotting beneath the park, still releases methane, a key cause of climate change. These wells pump it to a power plant, where it’s used to create electricity instead. “They’re phosphorescent and glow at dusk,” Olivier smiles. “They make it feel a bit sci-fi. Functional and fun.” Much like Montréal itself.

According to the Global Destination Sustainability Index, Montréal is North America’s most sustainable city. But while the Québec metropolis has a strong eco bent, it’s seldom without a playful edge. And Frédéric-Back quite literally has a playful edge.

The new park sits by the city’s Circus Arts Quarter: the legendary Cirque du Soleil moved its HQ to Saint-Michel in 1988, and later founded the National School of Circus and the Tohu circus and community complex here. It’s all part of reviving the area and bringing culture and entertainment to people for less; Tohu offers free bike and snowshoe hire for exploring the park, as well as running lower-cost events. Guide Stephanie (also a juggler and unicyclist, of course) shows me into Tohu’s large, circular, sustainably designed auditorium. “The massive doors at the back are tall enough for a giraffe, wide enough for an elephant,” she tells me. “That said, we’ve never tried.”

Montréal is a city of festivals: jazz, comedy, snow, beer – there will inevitably be something on, whenever you visit. For me, it was Tohu’s Complètement Cirque Festival (held in July), which Olivier helps run. And its bravura centrepiece is the Giant: a free, twice-nightly spectacular that sees a daredevil troupe flip, leap and dangle off a 50ft-high metal man. I join the crowds gathering beneath the skyscrapers in Place Ville-Marie. As the sun sets, the music starts, the lights spin and the show begins. Incroyable! So far so fun.

I don’t have far to wander home afterwards either. I was staying at nearby Humanti, a sleek hotel-apartment complex – it calls itself a “vertical village” – designed to connect city, visitors and local community. It’s a past Best Futura Project finalist, an accolade that recognises buildings whose distinct architecture and environmental ethos offer a glimpse of what the future could hold – and there’s plenty of smart thought here. I especially liked the abundance of both natural light and Canadian art, and – a nice detail – the gym’s wooden eco-machines, which use water resistance rather than electricity.

Olivier tells me that Montréal is a city that “rewards the wanderer”; a place where the joy is in making your own discoveries, sauntering through neighbourhoods, rather than ticking off sights. Perhaps it’s not so surprising that a city whose official language is French rewards the lifestyle of the flâneur. So that’s what I do.

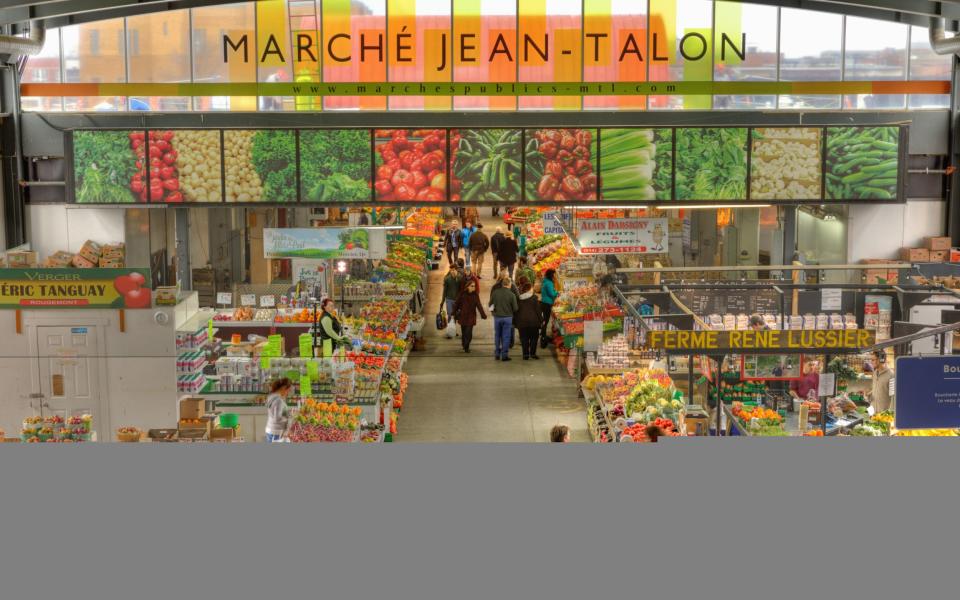

The next day I follow my nose up leafy Mount Royal, the city’s great, green lung, and down through affluent Outremont, with its cool cafés and Art Deco theatre. I amble into Little Italy, via streets of duplexes with spiral staircases – a Montréal architectural classic – and into cornucopian Jean-Talon market, brimful of fresh and local produce.

I browse environmentally friendly fashion at the vintage stores in Mile End – some, like Annex, out-chic-ing most designer boutiques. And I end up at the counter of Wilensky’s Light Lunch, a kosher café-deli that’s changed little since it opened in 1932. I order the Special, an all-beef salami and bologna roll, for $5.01, plus a cherry-cola from the soda fountain. The man next to me orders a Special too, wolfs it, then orders another.

After all this, I’m in need of a rest, so I catch a bus towards the Old Port, to sample the city’s sustainability at its most soothing. In the 1950s the Arthur Cardin was a ferryboat; now, in a nifty bit of recycling, it’s been revamped into Bota Bota, a floating spa powered by energy extracted from the St Lawrence River. Even eco-warriors can relax here.

The design is super-slick, a nautical-meets-Scandi vibe that flows through the hot pools, cold pools, steam rooms, saunas and chill-out garden. I move around, variously cooling and broiling myself, enjoying the prime views across the river and skyline, and up to the hulking industrial silos, built when Montréal was the biggest grain port in the world. However, for all the spa’s fancy areas, I like the simple deck where no one else was; here, I descend the caged-in steps for a dunk into the St Lawrence itself, watched only by the ducks.

Actually, it’s possible that the passengers aboard the Petit Navire see me too. When, a little later, I take a trip on this pleasure boat myself, we steer close to Bota Bota – without disturbing the spa-bathers inside. Petit Navire’s fleet is entirely electric powered; super-quiet, zero-pollution and carbon-neutral certified.

“It’s equivalent to running two hairdryers,” remarks Captain François as he steers around the old port, along the shire of St Helen’s Island and into the Sainte-Marie current. This fast-flowing undertow was historically an awkward obstacle for ships trying to dock here. For us today it is just fun. The fizzing water picks up the boat and, whoosh, we are speedily propelled towards the Jacques Cartier Bridge. Those hairdryer batteries have to work considerably harder to get us back again.

I have a little time to kill before my trip’s grand finale, so I head to nearby Pointe-à-Callière, Montréal’s archeology museum, located on the spot where the city was first founded in 1642. And it was excellent, especially the displays underground, where a Montréal has been brilliantly unearthed. Via artefacts and excavations, I explore the city’s layers, from traces of indigenous occupation to the original wooden palisade, first cemetery, a munitions store, 18th-century cobblestone streets, the remains of the Wurtele Inn.

But, to finish, I walk from basement to big top. Every year Cirque du Soleil erects a mighty tent by the old port; these days, it’s blue and white – the pale-coloured canvas reflects the heat and greatly reduces the energy needed for air-conditioning. I’m off to see Echo, the troupe’s latest show, themed around balance in nature and the importance of connection in creating a liveable world. The way Echo delivers its eco message was via human skill and dexterity at its greatest. Performers do impossible things around an enormous Rubik’s-like cube, itself twisting and shape-shifting. I’d wager there wasn’t a soul in the audience without their hands in their mouths, their hearts in their throats, or gasps, screams and whoops on their lips.

After two hours of being bamboozled, I emerge, stupid grin stuck on my face. On this evidence, Montréal seems just the kind of world in which I’d happily live.

Essentials

Air Canada (00 800 669 92222; aircanada.com) flies London-Montréal from around £350 return. Hotel Humaniti (001 514 657 2595; humanitihotel.com) has doubles from C$220pn (£130) room only. A three-hour session at Bota Bota costs from C$70pp (£41) (botabota.ca). Boat trips with Petit Navire cost from C$25pp (£15) (lepetitnavire.ca). For show listings, see tohu.ca and cirquedusoleil.com. For more information, see mtl.org/en.