The surprising history of the barcode

Editor’s note: The views expressed in this commentary are solely those of the writers. CNN is showcasing the work of The Conversation, a collaboration between journalists and academics to provide news analysis and commentary. The content is produced solely by The Conversation.

(The Conversation) — Few objects in the world are more immediately recognizable than the barcode. After all, barcodes are all around us — more than 6 billion are scanned every single day. They’re on the books we buy and the packages that land on our doorsteps. They’ve become such an accepted part of our daily lives that it’s hard to imagine how they could look any different.

I’ve researched various technologies throughout my career as a media studies professor, but it wasn’t until I began writing my book about the cultural history of the barcode that I realized how even the most mundane objects in our lives look the way they do because of decisions that are mostly lost to history.

When I began combing through the archive of barcode history at Stony Brook University, I realized just how close we came to a world where we scan bull’s-eye or sun symbols to buy our groceries.

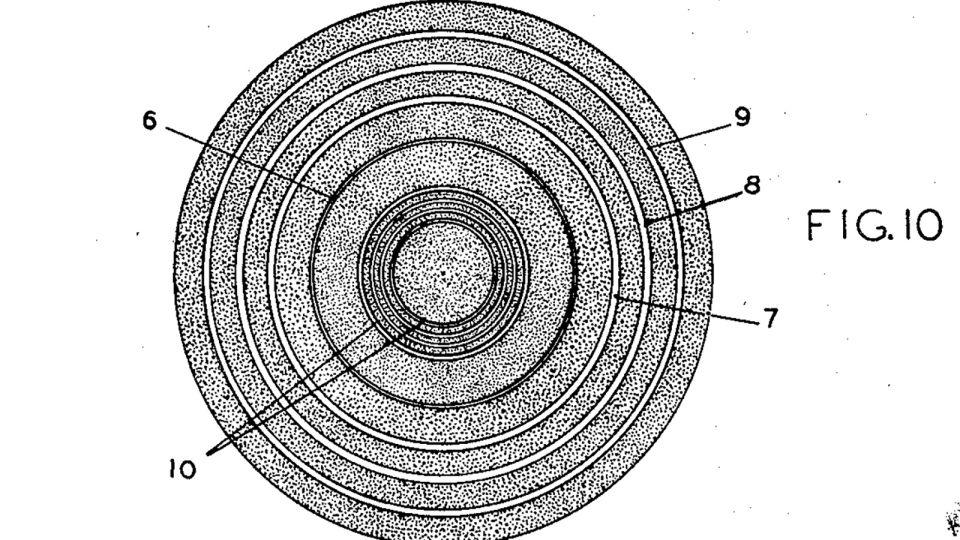

Our story begins in 1949, when Joseph Woodland and Bernard Silver submitted a patent for the first barcode. That patent described the basic structure of using pairs of lines to represent numbers that is still used in barcode technology more than 70 years later.

What their patent didn’t include, however, was anything most people today would recognize as a barcode. In fact, the first barcode didn’t include vertical lines at all. Instead, it used a series of concentric circles in the shape of a bull’s-eye.

Woodland and Silver initially struggled to get companies interested in their invention. But the barcode’s fortunes began to change in 1960, when the engineer and physicist Theodore H. Maiman built the first working laser, which made it possible to quickly decode a barcode’s line patterning.

Not long afterward, in 1967, the railroad industry implemented Kartrak, which was the world’s first official barcode system. Kartrak barcodes were developed to automatically identify rail cars as they moved past scanners, but they used a design of lines of varying colors that looks more like a piece of modern art than the barcodes we use today.

But Kartrak struggled from the start — the system wasn’t as accurate as people had hoped — and it stopped being used in the 1970s. Despite being the first barcode to be officially adopted by an industry, the multicolored design of the Kartrak symbol is now just a footnote in history.

Around the same time Kartrak was launched, the grocery industry set in motion a chain of events that eventually resulted in the barcode we know today. In the late 1960s, stores began barcode pilot projects that used vastly different types of bar code symbols.

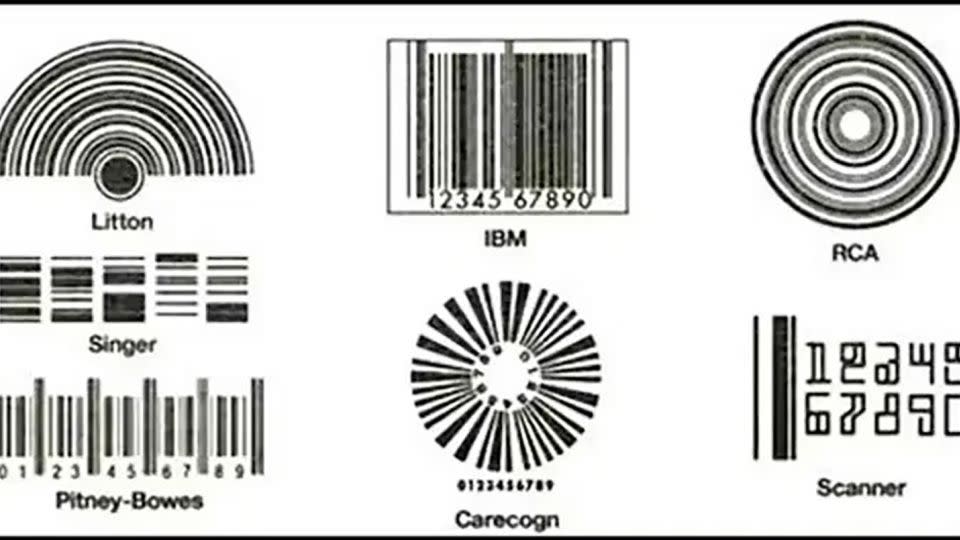

One of the symbols was the original bull’s-eye bar code, which by that point was owned by RCA (because it had purchased the patent rights). But other stores used symbols developed by other companies. For example, a company named Carecogn had developed a sun-shaped symbol; the Litton company created a fan symbol. The grocery industry soon realized that this Wild West period of experimentation couldn’t last.

Barcodes could work as a way to automate inventory and checkout only if everyone in the grocery industry agreed to use the same symbol. Otherwise, the system would be overly complex and expensive. So in 1971, the grocery industry formed a committee tasked with developing an industrywide data standard and choosing a symbol that stores would agree to adopt.

The data standard the committee developed — the Universal Product Code — was designed to work with different types of barcode symbols. The committee then had to choose the symbol. They solicited applications from various companies and narrowed the pool down to seven finalists. That was when the drama really began.

The RCA submission was the early leader among the seven finalists. The bull’s-eye barcode, after all, was the original barcode symbol, and RCA was a powerful company that had invested significant resources in developing the technology. RCA’s main competitor was a latecomer to the battle for barcode dominance: the IBM symbol invented in the early 1970s by George Laurier.

Between 1971 and 1973, the committee extensively tested the seven finalists, listened to pitches from each company and met multiple times to discuss the path forward. Throughout the process, RCA and IBM remained the front-runners, and in a somewhat ironic twist, Joseph Woodland — the “father of the barcode” and inventor of the bull’s-eye symbol — advocated for the IBM symbol over his own invention.

Realizing their symbol might not be selected, RCA began to pressure the committee and threatened to pull out of the barcode industry altogether if their bull’s-eye was not chosen as the standard.

The committee’s deadline to select a symbol was March 1973, and the decision went down to the wire. In its final meeting, the committee chose the IBM symbol despite concerns that, to quote the historian Stephen Brown, “by opting for the oversquare symbol instead of the bulls-eye, the Committee may have dramatically slowed the pace of implementation” because of RCA’s pressure.

The IBM symbol became the industry standard, and the very first Universal Product Code barcode was scanned at a grocery store in Troy, Ohio, on June 26, 1974. Rather remarkably, the IBM symbol the committee chose is still going strong almost 50 years later. The barcodes you scan at a grocery store are essentially the same barcodes someone would have scanned in the 1970s.

Based on meeting notes from the symbol selection meetings, committee members felt they were doing important work. But even in their wildest dreams, they could not have imagined how consequential their decision ended up being.

The barcode design they selected became one of the most iconic images of capitalism and has inspired architects’ building designs, symbolized dystopian conformity in science fiction, become a popular tattoo and even inspired online fan communities.

But the design that changed the world came remarkably close to being a forgotten piece of history. If a few grocery executives had voted a different way, we might be moving through a world filled with bull’s-eyes.

Jordan Frith is the Pearce Professor of Professional Communication at Clemson University in Clemson, South Carolina.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com