Are There Still Mysteries in Paris?

‘‘People will always tell you that Paris was better 20 years ago,” a lover of the city said to me once. And the thing is…this is always true. Roll back any period in the city’s history by 20 years and you will find a better period—at least, as judged by those looking back. Those of us who lived in the city in the 1990s, myself included, remember how beautiful its defiance of late modern values was at the height of the American imperium, when, after Paris had been dismissed for years by London and New York as a backwater, the millennium happened, and Paris won the night. Every big city shared its New Year’s celebration over CNN, but it was the Eiffel Tower, as it bubbled and shimmered like a glass of champagne, that emerged as clearly still the best and shapeliest and most radiant of all modern beacons. Paris, though down, was far from out.

But the 1990s city, as even I can recall, was a superficial-seeming place compared to the Paris of the early 1970s. That one was still rocking in the wake of the rebellions of May ’68, still incompletely cleaned and gritty with unresolved revolutions and repertory cinemas. You entered the Louvre by the back door, so to speak, without a grand and glaring pyramid, and the Marais was just rediscovered and reclaimed, but not yet unduly gentrified. The Rue des Rosiers, in the 4th Arrondissement, was still a distinctly Jewish street.

Of course, roll back 20 years before that, and we come to the 1950s, idyllic at least for Americans in those years of cheap francs, when the Paris Review and the James Jones crowd flourished, in a kind of GI Bill–financed version of the 1920s. And then roll back to those 1920s in Paris, which hardly need any PR, so memorable have they been made by writers from Hemingway to Janet Flanner. And we can keep rolling, right back to the pre-Revolutionary period, about which Talleyrand said that anyone who had not lived in the 18th century, before the Revolution, did not know the sweetness of life. The premise, of course, has to come to an end sometime, at some degree zero, but it doesn’t seem to. It’s not that the past always looks rosier. It doesn’t: No one wants to revisit the Paris Commune, or the Terror, or the Occupation. It’s that each period in the Parisian past has a distinct aura, a special atmosphere, a quiddity of its own that is so striking, in retrospect, that we long for it a little even as we have our new Paris now.

And a new Paris is certainly unrolling before our eyes. Those of us raised, so to speak, in the 5th and 6th and 7th arrondissements, on the Left Bank, now seek out friends and feasts in the more arctic 9th and 19th. This is true of every big town, of course. The youthful heart of New York City has transplanted itself at least three times in my own lifetime, from Soho to the East Village to Williamsburg and other points Brooklyn. We learn to love the peculiar sights of the new neighborhoods, and so we Paris lovers can appreciate the Canal Saint-Martin and its boats as we once did the Seine and its books. Paris, too, has had some very hard days recently. It has been sporadically buffeted by violence, with the Bataclan and Charlie Hebdo massacres still hideously memorable. Though Paris has always been a site of violence, there is something nihilistic about the new kind, and so our inevitable longing for the Paris that’s gone meets our at least partial fear of the Paris that’s coming, and melancholia can overtake even Francophilia.

We try to shake ourselves awake, and the proper, cold-blooded thing to say is that we must outgrow all those accumulated nostalgias and embrace, or at least inspect, Paris as it now is. (The merely touristique thing to do is ignore what now is and go again to what once was.) Yet what it now is…is no one thing. So we go back to take favorite walks to try to recapture our old Paris while traversing the new one. Proust long ago warned us that streets are as “fugitive” as the years, and yet the lure of the Paris labyrinth is absolute. We walk the same blocks to try to relive the same emotions.

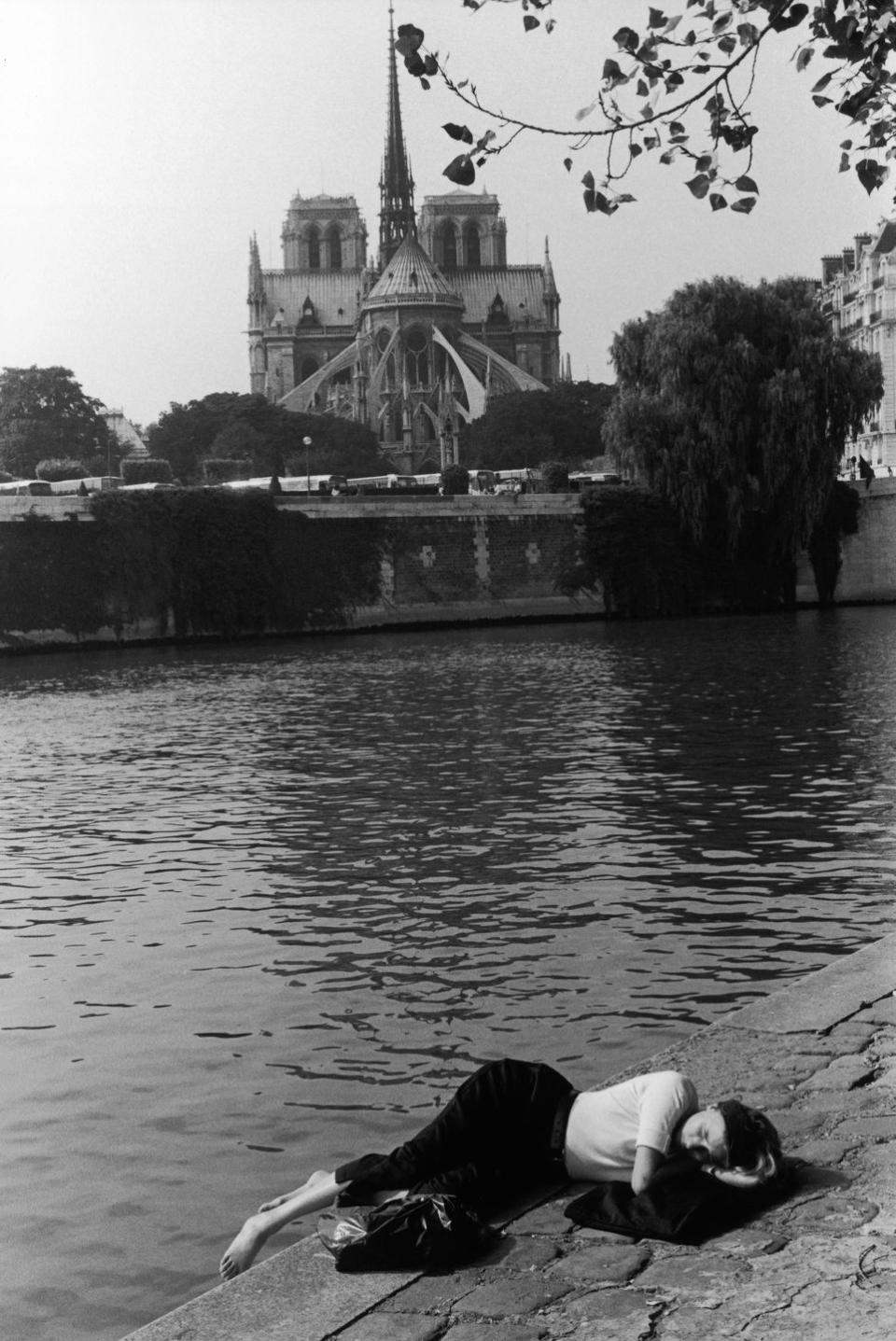

I have taken the same midnight walk, from the Brasserie Balzar on the Rue des Ecoles to the corner of the Rue du Bac, a thousand times—down the Rue de l’Odéon, and then along Saint-Sulpice, up the Rue Bonaparte to the Boulevard Saint-Germain and what was, for a few happy years, home. (Now we revisit it as tourists.) The walk always seems to me not familiar but somehow enticing, unknown—unparsed, long-shadowed, a bit of found de Chirico mystery and melancholy. And though Giorgio de Chirico was an Italian painter supposedly looking back at Italy, as in his 1914 Enigma of a Day, it is no accident that he was living in Paris when he painted those great pictures, with Paris imprinted on his imagination.

The sense of accidental happiness—that girl with the hoop in de Chirico’s Mystery and Melancholy of a Street, having a good time in the midst of historic melancholia—is somehow a Parisian one. For that is the keynote of Paris: mystery. We don’t recapture the city we once lived in, nor do we feel compelled to embrace a new one, as we may in New York, where Bedford Avenue in Williamsburg claims the place that Manhattan’s West Broadway once held. In Paris we look for the parts that baffled us once, and ask them to baffle us again.

The Mysteries of Paris, Eugène Sue’s little-known 1842 novel—well, everyone knows the title; few know the book—insists that what is mysterious is exactly everything in Paris, from the composition of the elite to the layout of the Latin Quarter. The book’s atmosphere is itself memorably mysterious, and it created a kind of noir genre of the sinister urban nocturne, one that by now has been set everywhere from Reykjavík to Pittsburgh. We want our cities to be enigmas of slanting light and long shadow, and Paris was the first.

We may even begin to itemize some of the mysteries. Why are the 17th-century buildings tilted back in their upper stories? No one quite knows. Why is the Louvre called the Louvre? No one knows that, either. Why is Paris the only major city organized around courtyards and codes, so that we go home with our pockets filled with little bits of paper with the codes of our friends’ apartments scribbled on them. It never happens in London or Rome or Los Angeles. There are reasons, but no rationale. Even the smaller, historically rooted but mystifyingly firm distinctions between bistros and brasseries can be the subject of a seminar. (The bistro is a survivor of the premodern period, when you went to a “table d’hôte” to eat what was provided, adapted to the customs of the early modern period, when the “restaurant” emerged as a place to go and pick out what you wanted. The brasserie emerged only in the mid-19th century, as a resort of Alsatian pleasures, centered on drinking beer.)

Those nostalgias accumulate exactly because they’re not really nostalgias. The mysteries of Paris are permanent because they are built into the pavement. We go back to Paris for a renewed sense of the unfathomable that no other place provides. If Paris were less murky, it would be less Paris. The enigmas defy too much explication because, well, they’re enigmatic. Once, for instance, I sat in a rented apartment on the Rue de Grenelle and watched the sun set over nothing more than the entrance to a Métro station across the street, one of the 86 historically protected ones, still with its late-19th-century Hector Guimard melting iron entrance. It seemed somehow—the people flowing in and out, the dome of the Invalides beyond—to indicate European history, and I felt in touch with a flow of time and melancholy. I can sit and passively watch things in Paris and feel more civilized than when I do productive things elsewhere. Outside that window was a flow of existence, simultaneously past and present, that seemed impossible to imagine in rushed and pressed New York, or spacious and sensible London.

Oh, come now! Only in your imagination. Only in my imagination? Well, our imaginations are where our images reside. All other cities I know, however ancient, have their own odd lucidity. A New York city block is an equation parsed, an intersection on a prearranged grid. Rome makes us happy when it is most picturesquely Roman, seeming to arise from Fellini and Suetonius simultaneously. And London is London when the elementary colors take over the town, and the taxis look blacker and the buses redder than we could have imagined.

But Paris occurs as a sequence of emotions we recapture and then lose. We never feel that we own it, and that is why it is capable of surprising us. De Chirico’s great poetic promoter, Apollinaire, resolved a Parisian poem with the haunting phrase: “The night is a clock chiming. The days go by not I.” He was evoking—okay, mysteriously evoking—the city, meaning that we somehow hear the clocks chime all night but feel ourselves remain unchanged, and then wake to find that the world has altered.

When I go back to Paris these days, the city seems to enfold me again without welcoming me entirely. The city goes on, through everything that happens, and will continue to go on when we are no longer there to see it. The next hundred years will still be divided into 20-year packets, and we will still long for the time before, even as we relish the time we’re in. The mystery of Paris as a city seems to enfold the mystery of our mortality. Nothing changes visibly within us, yet life moves on around us and we look in the mirror going home and find ourselves transformed. We will never solve the mystery of Paris, nor would we want to, which is why we keep going back, with a clue or two to bring home kept in our pocket.

This story appears in the Summer 2024 issue of Town & Country. SUBSCRIBE NOW

You Might Also Like