Ancient abodes: the world's oldest homes may surprise you

Ancient abodes that have survived into the 21st century

![<p>Rod Waddington / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/ib5gbxteL5erKwdb6tOBBw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/a4f7e7a12e99c30ae06b342aefb377d1)

Rod Waddington / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0]

They certainly don't build them like they used to! Constructed many centuries ago, the world's oldest intact homes have stood the test of time and witnessed huge changes in human history.

Read on to take a trip back through the ages and discover the most venerable residences on the planet that are still inhabited today, from astonishing cave houses to noble manors.

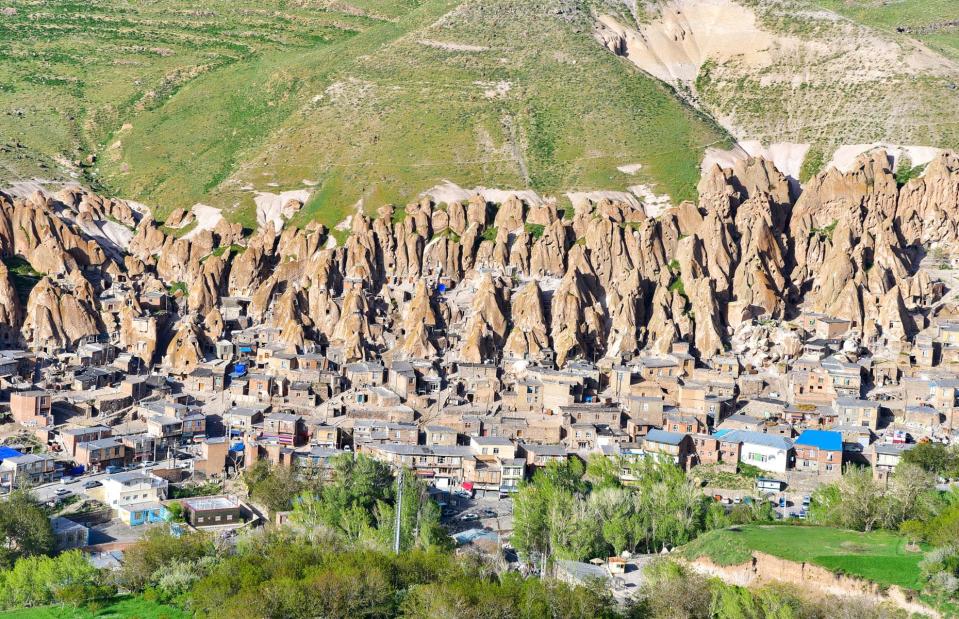

Kandovan cave houses, Osku, Iran

Andrea Lehotska / Shutterstock

Nestled at the foot of the Mount Sahand volcano, the remarkable village of Kandovan in Iran's northeastern East Azerbaijan Province is made up of troglodyte homes that were carved out of the soft, porous volcanic rock 700 years ago by refugees fleeing the Mongol hordes.

Troglodyte translated from Greek means 'cave-dweller' in English. These cave houses are called Karaans, possibly after the local dialect word for beehive.

Kandovan cave houses, Osku, Iran

BEHROUZ MEHRI / AFP / Getty Images

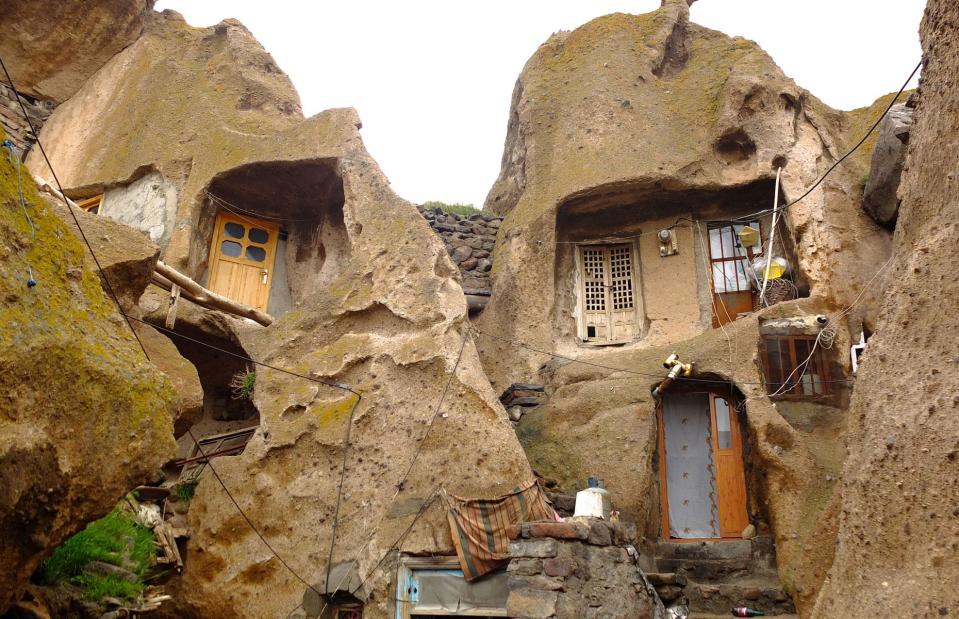

Continuously inhabited since their creation, the cliff houses are carved into fantastical shapes that look straight out of a fairytale.

For centuries, they have protected the village's inhabitants from enemy invasions, not to mention the region's blisteringly hot summers and bitter winters, thanks to their precarious position and wonderfully insulating walls.

Kandovan cave houses, Osku, Iran

Robert Szymanski / Shutterstock

The homes can stretch up to four storeys in height. The ground floor traditionally houses livestock, living quarters are situated on the next two floors, while the upper level is used for storage.

As you might imagine, Kandovan is now a major tourist attraction and the village, which has a population of 670, usually welcomes 300,000 visitors a year.

Kandovan cave houses, Osku, Iran

Matyas Rehak / Shutterstock

Kandovan is not only home to these incredible troglodyte dwellings: the village's spring water is said to be healing, plus many of the plants that grow in the area are reported to have restorative properties.

To accommodate the ever-growing number of visitors, a cave hotel opened in 2006, while this gift shop caters to tourists.

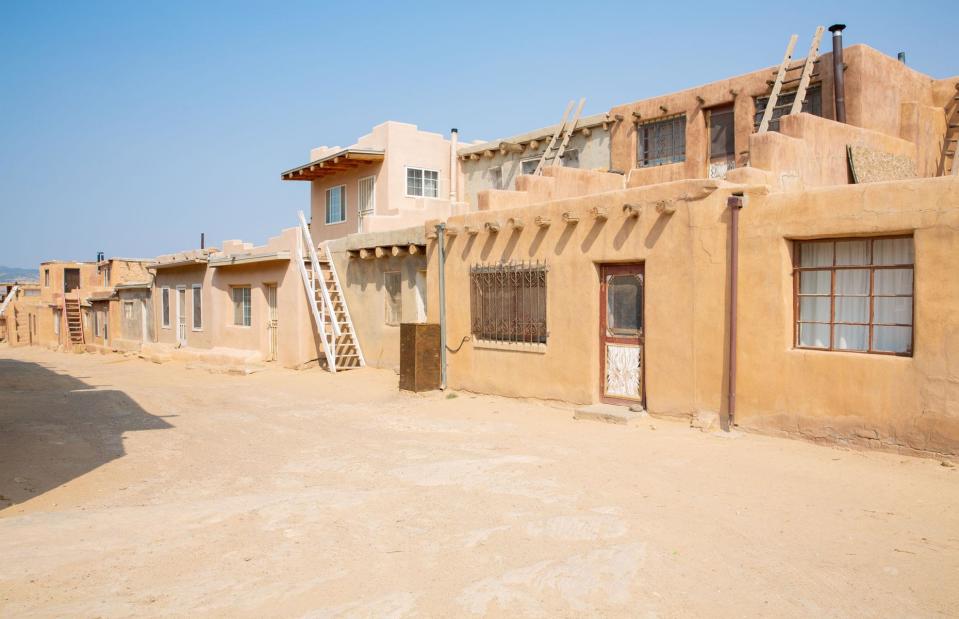

Sky City, Acoma Pueblo, New Mexico, USA

![<p>Marshall Henrie / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/wuyA6eSQncUch4ToBBSxoA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/0b8f33762e19fefe4efe4e816d877e4c)

Marshall Henrie / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0]

Acoma Pueblo near Albuquerque in western New Mexico was established in at least the 12th century, though according to the Native American Acoma people, it was even earlier.

The earliest surviving homes in the village sit atop a 367-foot (112m) mesa. A mesa is a flat-topped hill or mountain with steep sides and the word comes from the Spanish word for "table" because the tops of mesas look similar.

The homes are said to have been built between 1144 and 1150 and archaeologists believe the elevated location was first inhabited as far back as 2,000 years ago.

Sky City, Acoma Pueblo, New Mexico, USA

![<p>NewMexicophotographer1 / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/rrc_M2c7_5ZkwpqUEmBWIg--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/3f739fd1da995e48c0524a92414d4ea9)

NewMexicophotographer1 / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0]

The area became known as the 'sky city'. The mesa was the ultimate safe haven for the community's early inhabitants, who were exceedingly well protected from Navajo and Apache raiders.

The sheer faces of the flat-top hill made the village pretty much impregnable and for centuries the only access was a staircase carved into the sandstone, which could be easily defended.

Sky City, Acoma Pueblo, New Mexico, USA

Traveller70 / Shutterstock

Numbering some 300, the pueblo's structures were built using sandstone and adobe bricks, which are made by combining earth, straw and water. They are constructed as multi-level terraces entered by ladders rather than doors.

As well as having a spiritual significance, these ladders could be removed in the event of an invasion, further protecting the inhabitants from marauding tribes.

Sky City, Acoma Pueblo, New Mexico, USA

![<p>James Slack / Wikimedia Commons [public domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/egFW.iyaGCNvuX7clTbsgg--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/5326d2f40a108f8b02ededd560d2c3bd)

James Slack / Wikimedia Commons [public domain]

This image from 1934 shows the interior of one of the pueblo's homes, specifically one of their characteristic corner fireplaces.

Sky City also features a number of external adobe beehive hornos ('ovens') that were used for baking, cooking and firing pottery, for which the pueblo is famous the world over.

Today you can visit the city to learn more about its long history and get involved with calendar events such as San Esteban Feast - the Harvest Dance or take a guided tour.

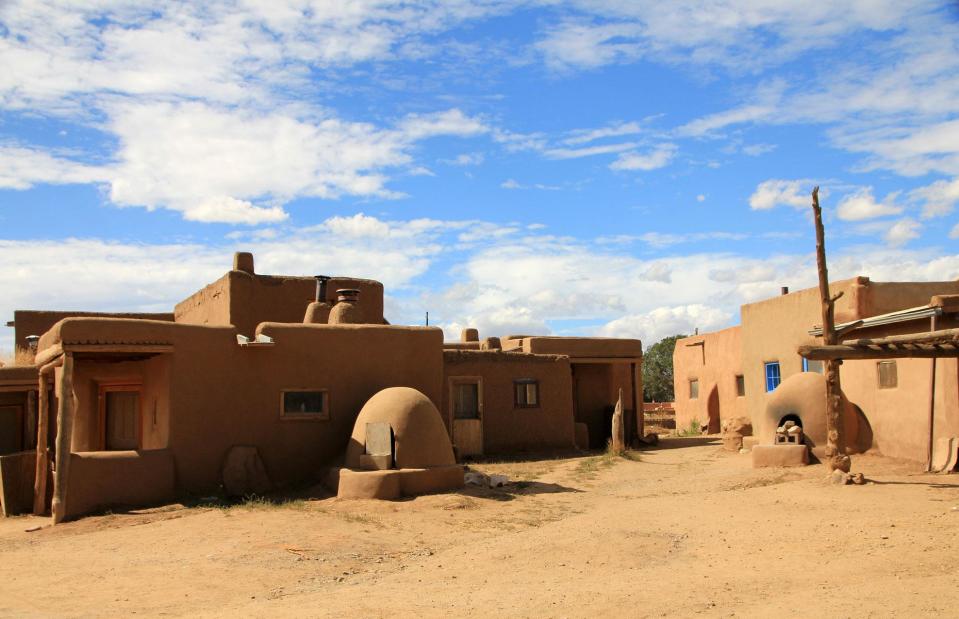

Adobe houses, Taos Pueblo, New Mexico, USA

Gimas / Shutterstock

Staying in New Mexico, Taos Pueblo is likely the oldest continuously inhabited site in the US, possibly predating Acoma Pueblo by around a century.

The home of the Native American Red Willow People for more than a millennium, the village is located in a high desert valley within the Sangre de Cristo Mountain Range on either side of the Rio Pueblo.

Adobe houses, Taos Pueblo, New Mexico, USA

![<p>John Phelan / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/WCaQEpOti2Eu3AIdYXIe4Q--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/b435428d4d45c3fe1ba29404cacc1e9c)

John Phelan / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0]

Designated as both a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a National Historic Landmark, the pueblo is made up of two multi-level apartment-style adobe houses.

The Hlauuma ('North House'), stands five storeys high and is said to be one of the most photographed buildings in the US and the Hlaukwima ('South House').

Adobe houses, Taos Pueblo, New Mexico, USA

![<p>Lewis H. Morgan / Wikimedia Commons [public domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/8dVhd8B9FaOZAcvVz8v2AQ--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/0614de8dbfbbd659e5c7900f433f1364)

Lewis H. Morgan / Wikimedia Commons [public domain]

The village's adobe houses share many similarities with the homes of Acoma Pueblo, as this picture from 1877 shows. The thick adobe walls provide excellent insulation, keeping the rooms cool in summer and warm during the winter months.

Like Acoma's structures, they were traditionally accessed by a ladder, though some went on to feature doors and ground-floor rooms were kitted out with corner fireplaces.

Adobe houses, Taos Pueblo, New Mexico, USA

Lucy / Shutterstock

The similarities don't stop there. Taos Pueblo is also dotted with beehive-shaped adobe hornos and, like Acoma Pueblo, has no electricity, running water or indoor plumbing, which are prohibited for religious reasons.

Other interesting features of the village include wooden racks used to dry meat, corn, berries and animal hides.

Saltford Manor House, Somerset, UK

Adrian Sherratt / Alamy Stock Photo

One of two contenders for England's oldest continuously inhabited home, the five-bedroom Grade II-listed Saltford Manor House in Somerset holds a wealth of history within its walls.

Architectural historian John Goodall has dated the house to before 1150, possibly around 1148, and it's entirely possible that this site was also used as a residence when the Romans ruled Britain.

Saltford Manor House, Somerset, UK

![<p>Hugh Llewelyn / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 2.0]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/XSSe7Gd4KmE90XqcwIp6Mg--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/7e40bb9b54a5713836f4d5b0818e34d0)

Hugh Llewelyn / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 2.0]

The Norman manor was constructed on land that belonged to the Earls of Gloucester and Bishop of Coutances Geoffrey de Montbray, a close confidant of William the Conqueror.

The house passed through numerous owners before it was acquired by the Duke of Chandos in the late 1700s. The house was then bought by the Flower family, who owned the property until the late 19th century when it was sold to a local farming couple.

Saltford Manor House, Somerset, UK

![<p>Hugh Llewelyn / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 2.0]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/v9btT8WEoYFNwDjXGYm5ig--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/99f3065f11083d7ffe250e5b4bda7682)

Hugh Llewelyn / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 2.0]

The manor fell into a dilapidated state during the early 20th century but was eventually renovated by James and Anna Wynn, who snapped up the rundown property in 1997 for £300,000 ($393k) after selling their relatively modest terraced house in London.

The couple oversaw the addition of a barn, outbuildings and a garden room. The chapel at the rear of the house sadly collapsed and was not replaced. The couple ended up offloading the manor in 2010 for a very tidy £1.3 million ($1.7m).

Saltford Manor House, Somerset, UK

![<p>Rick Crowley / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 2.0]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/9xZezXEtynRQ3_MzbCUW3A--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/85cfdc43463dfe54750c28b882cdcb01)

Rick Crowley / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 2.0]

Like many ancient houses, the manor has undergone many changes and additions over the course of its history like an upgrade to a Tudor fireplace and a 17th century kitchen.

However, besides its Norman features, which include a window in the master bedroom that closely resembles one in Hereford Cathedral, the house still contains numerous notable pieces of history.

This includes 13th-century wall paintings, considered to be the oldest surviving medieval frescos in England. The Early Medieval wall paintings on the first floor were discovered by Saltford Boy Scouts in the 1940s whilst using Saltford Manor House as their HQ.

Viking farmhouse, Kirkjubøur, Faroe Islands

![<p>Vincent van Zeijst / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/BSUd1Y2Mwh9zgwrbCJb7.g--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/700a8208c99be0e5d562d943e45a4bb8)

Vincent van Zeijst / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0]

Kirkjubøargarður ('Yard of Kirkjubøur') aka 'King's Farm' in the windswept Faroe Islands is one of the oldest continuously inhabited wooden homes in the world and could very well be the most venerable.

The remote farmhouse was constructed in the 11th century using driftwood from Norway. This is interesting as the Faroe Islands are virtually treeless and timber has long been a precious commodity.

Viking farmhouse, Kirkjubøur, Faroe Islands

Roland Knauer / Alamy Stock Photo

The Viking farmhouse, which like many traditional structures in the Faroe Islands features a turf roof to keep out the elements, first served as a Catholic episcopal residence and seminary.

It was here that Bishop Erlendur penned the so-called 'Sheep's Letter' in 1298. This royal decree concerning sheep breeding is the earliest known document created in the Faroe Islands. It was enacted by Duke Haakon, who later became King Haakon V of Norway.

Viking farmhouse, Kirkjubøur, Faroe Islands

![<p>Erik Fløan / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/3enX_YdCb4DacNf8e9ugeA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/c45889df6b319572424c07b5c0389571)

Erik Fløan / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0]

In 1538, not long after the Protestant Reformation, the farmhouse was confiscated by the King of Denmark. Kirkjubøargarður was leased to the Patursson family in the 1550s and has passed through 17 generations, with the eldest son who is dubbed the King's Farmer, always assuming the tenancy.

Today, the ultimate owner of the property is the Faroese government.

Viking farmhouse, Kirkjubøur, Faroe Islands

![<p>Erik Fløan / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/jlIwd9hEfkF270aMcF9Z2A--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/fd5d643da2704f0bc95ee69b8165f274)

Erik Fløan / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0]

The farm remains the largest in the Faroe Islands and the current custodians raise sheep and cattle. Visitors can take a tour of the interior of the farmhouse, which is as cosy as they come and filled with a plethora of age-old artefacts.

You can also explore the surrounding historic buildings that include the 12th-century St Olav's Church and the ruins of the 13th-century St Magnus Cathedral.

Old Sana'a tower houses, Sana'a Governate, Yemen

![<p>Dan from Brussels, Europe / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 2.0]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/J3iDH7Wz6r8_Js8nXRZMNQ--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/7425a393c22d3e6d4f303742f777063c)

Dan from Brussels, Europe / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 2.0]

The ancient city of Old Sana'a high up in the Yemeni Mountains dates back more than 2,500 years, making it one of the most esteemed continuously inhabited urban areas on the planet.

A UNESCO World Heritage Site, Old Sana'a is renowned for its rammed earth tower houses. As many as 6,000 of these multi-level homes were constructed before the 11th century.

Old Sana'a tower houses, Sana'a Governate, Yemen

![<p>Rod Waddington / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/WW3t62QZhjkZj.Jbot7cqw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/a91257219b954706b989be2266ff3813)

Rod Waddington / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0]

Dubbed the 'world's oldest skyscrapers', these lofty buildings soar up to nine storeys and boast intricate geometric friezes crafted from fired bricks and white gypsum punctuated by colourful stained glass windows, which contrast beautifully with their ochre façades.

Sadly, these extraordinary structures are under threat like never before.

Old Sana'a tower houses, Sana'a Governate, Yemen

Sebastiano Tomada / Getty Images

Yemen has been in the grip of a devastating proxy civil war since 2014, after Iran-backed Houthi rebels ousted the Saudi-aligned government and took control of Old Sana'a and other parts of the country.

Since then, the city has been battered by Saudi-led airstrikes, which have destroyed a number of its iconic tower houses and many of those that are still standing are suffering severe neglect.

Old Sana'a tower houses, Sana'a Governate, Yemen

Xinhua / Alamy Stock Photo

Adding to the multiple threats to the city's heritage, Old Sana'a endured months of exceptionally heavy rains in 2020. Weakened by the forces of Mother Nature and widespread flooding, 111 tower houses collapsed and 6,000 dwellings have leaky roofs.

With the war showing no sign of ending, the situation is only likely to get worse. Let's hope some of these incredible homes survive.

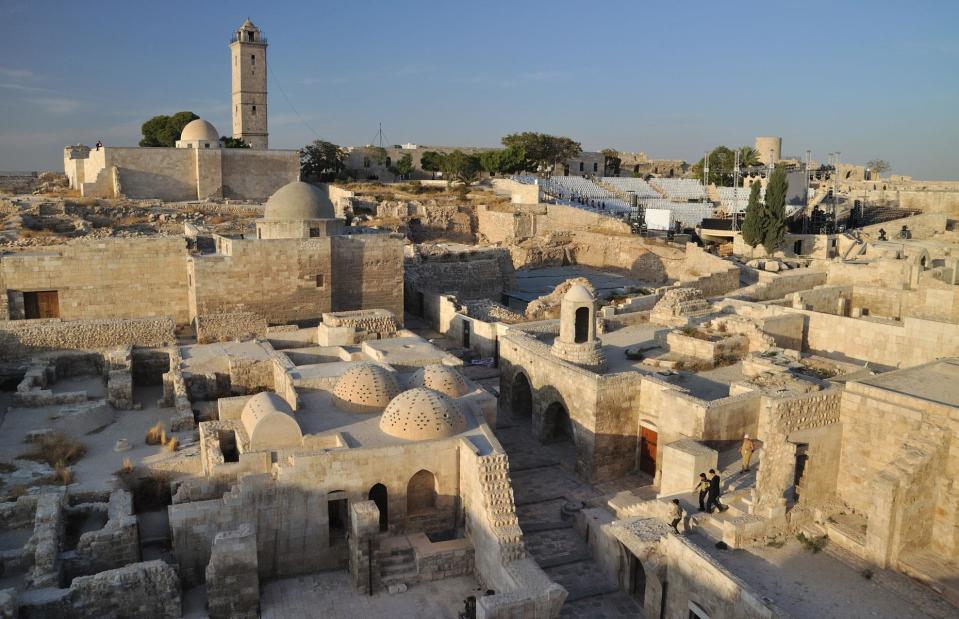

Aleppo Citadel houses, Aleppo Governorate, Syria

![<p>Anas Al Rifai / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/SZjvLicsRNtulWA7J5aZYw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/cfaf911ec63edf8b169fd4d83a0b4560)

Anas Al Rifai / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0]

From one war-torn place to another, Aleppo's ancient Citadel which looms over the Syrian city, dates way back to the third millennium BC. However, the majority of the residences within its walls were erected by the Ayyubids during the 12th and 13th centuries.

Full of history, the UNESCO World Heritage Site has withstood everything from earthquakes to sieges over the centuries.

Aleppo Citadel houses, Aleppo Governorate, Syria

Dziajda / Shutterstock

Starting out as a temple to the Mesopotamian storm god Hadad, the citadel was first used as a fortification by the Macedonians in the third or fourth century BC.

It was conquered by Muslim forces in 636 AD and later became the capital of the Hamdamid dynasty before it was sacked by the Christian Byzantines in 962 AD.

Aleppo Citadel houses, Aleppo Governorate, Syria

vyskoczilova / Shutterstock

Thereafter, the citadel was occupied by the Zengid, Ayyubids, Mongols and Mamluks, eventually falling into Ottoman hands in the 16th century.

Throughout its long history, the fortified palace has been damaged and restored numerous times but was never completely destroyed, which gives testament to its resilience.

Aleppo Citadel houses, Aleppo Governorate, Syria

![<p>Bernard Gagnon / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/W_H35MUeo4TiK5K5VLGlTw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/b94d468fd2230101458bfc72fb7464cd)

Bernard Gagnon / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0]

The Mamluk Throne Hall was restored by the French during the 19th century and then extensive conservation work was carried out in the 2000s, funded by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture.

During the 2010s, the citadel was severely damaged during the four-year Battle of Aleppo. It reopened to the public in 2017 and is currently undergoing yet another major restoration.

Cave houses of Sassi di Matera, Basilicata, Italy

![<p>Bönisch / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 2.0 DE]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/D0yo54w.TSzueG4Ap1tHdA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/a649aa0cf5e086052a15fcc1fb7bb438)

Bönisch / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 2.0 DE]

Carved out of calcarenitic rock, the cave houses of Sassi di Matera ('Stones of Matera'), comprise two districts called Sasso Caveoso and Sasso Barisano within the age-old city of Matera in southern Italy's Basilicata region.

They have been inhabited since the Palaeolithic period. Incredibly, archaeological evidence shows people lived in the grottoes as far back as 7000 BC.

Cave houses of Sassi di Matera, Basilicata, Italy

sergio capuzzimati / Shutterstock

Unlike some of the other homes in our round-up, these troglodyte dwellings were far from comfortable and extreme poverty and disease were rife right up until the middle part of the 20th century.

The slum districts were considered so deprived that there was a phrase used in the local area that 'even God has forsaken them'.

Cave houses of Sassi di Matera, Basilicata, Italy

MikeDotta / Shutterstock

While the majority of locals were relocated in the 1960s, people continued to live in the same houses their ancestors resided in 9,000 years ago.

Thankfully, the Sassi's fortunes turned around spectacularly during the late 20th century following the district's designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1993. The Italian government sponsored a number of restoration and infrastructure projects.

Cave houses of Sassi di Matera, Basilicata, Italy

cosca / Shutterstock

Artisans moved into the renovated cave dwellings and a plethora of bars, restaurants and hotels opened when Matera won its bid to become the 2019 European Capital of Culture.

In an average year, the Sassi attracts an impressive 600,000 visitors to its unique houses and upwards of 25% of the properties are available to rent out through Airbnb – more than anywhere else in Italy. The atmospheric town was also used as a filming location in the 2021 James Bond movie, No Time to Die.

Henry VIII's medieval manor, Wales, UK

coolstays.com

Originally built in the 13th century, with an extension added in the 16th century, this spectacular Grade II-listed country manor house was once the property of Henry VIII.

Llanthony Secunda Manor, as the property is known, is situated in Caldicot, South Wales and is steeped in as much historic charm and medieval character today as it was when it was constructed many centuries ago.

Henry VIII's medieval manor, Wales, UK

coolstays.com

The home is believed to have fallen into the possession of Henry VIII after the dissolution of the monasteries in 1536 and is currently being offered as a holiday let. Allowing guests to live like royalty for a few nights it has correspondingly steep rates of £700-£1100 per night.

While the property has certainly been refurbished to bring it up to modern-day living standards, it still boasts plenty of 13th-century details, including flagstone floors, exposed beam ceilings and enormous stone fireplaces.

Henry VIII's medieval manor, Wales, UK

coolstays.com

On the ground floor, you’ll find a magnificent formal entrance hall, as well as a study, cloakroom, storeroom and kitchen/breakfast room complete with an original 15th-century bread oven.

An original spiral staircase with a rope handrail leads to the first floor, where you’ll find the formal living and dining rooms. In both spaces, exposed stone walls, rustic wooden floors, cobblestone hearths and latticed windows combine to create an atmosphere as medieval as the structure itself.

Henry VIII's medieval manor, Wales, UK

coolstays.com

The home’s master bedroom can be found just off the dining hall. The showpiece of this room is the ornately carved canopied bed fit for a king, as well as a glamorous ensuite, which is certainly more modern than medieval, equipped with a bidet, clawfoot soaking tub and glass walk-in shower.

The bathroom is a stunning example of some of the contemporary updates that have been made to the home, which are still in keeping with its heritage and design.

Wings Place, Sussex, UK

Simon Dack / Alamy Stock Photo

Another Henry VIII heritage property, Wings Place in Sussex, is also sometimes known as the Anne of Cleves house. When Henry VIII released Anne from her marriage contract, he quite literally gave her 'Wings', this timber-framed Tudor cottage, as her new place of residence.

One of the very few Grade I-listed properties available for private ownership, Wings Place was last on the market for £2.3 million ($2.9m).

Wings Place, Sussex, UK

![<p>Rob Farrow / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 2.0]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/.yJo2Gbnvt6kU9ZWHZXtkQ--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/6157cce0b547855b9f869de9d07a1ad3)

Rob Farrow / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 2.0]

And if that weren’t enough of a historical pedigree, the home stands on a site which has been inhabited for nearly a thousand years, initially in the form of a manorial estate and later as a priory, which is first mentioned by name in 1095.

During the reign of Henry VIII, although prior to Anne’s ownership, the upstairs rooms of Wings Place were believed to have been used for secret Catholic services, while the ‘priest hole’ at the top of the staircase was supposedly a well-used hiding place.

Wings Place, Sussex, UK

![<p>Rob Farrow / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 2.0]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/d8HdN1je6Oboyp8M5eqBkw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/2721bac0aff8ed841a4135a01dcbec96)

Rob Farrow / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 2.0]

The home includes five bedrooms and five bathrooms across 4,263 square feet (396sqm), all of which are packed with flagstone floors, ornamental timbers, leaded light casement windows, carved bargeboards and tall brick chimneys.

In fact, Wings Place is so packed with period charm that architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner described the house as "eminently picturesque in a watercolourist’s way.” What more could you ask for?

Wings Place, Sussex, UK

![<p>Rob Farrow / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 2.0]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/Jt9Hz77QsZZ3M7NPyukgbA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/bbde8f4d175ba82a3b47383ce317c25a)

Rob Farrow / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 2.0]

The house is also full of cosy nooks galore from inglenook fireplaces to cosy reading spaces tucked behind hand-carved doors to bedrooms nestled beneath steeply-pitched beamed ceilings.

However, chefs will be relieved to learn that the home does include a contemporary kitchen, which boasts a full-range stove, under-floor heating, a central island and a fabulous north-facing gable window with views of the garden.

Serravalle, Emilia-Romagna, Italy

![<p>AnetaMalinowska / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/7r2zoR68wgOwnxs8MaTS4Q--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/c53547ceae5473929f71b35749b50202)

AnetaMalinowska / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0]

Located in the Emilia-Romagna region of Italy, halfway between the cities of Modena and Bologna, lies the magnificent medieval tower and hamlet of Serravalle.

Wonderfully historical, the current settlement is built on the foundations of an ancient Roman village, which was destroyed in the 8th century. Rebuilt a century later, today the medieval entrance and lookout tower (which dates as far back as 1227) remain.

Serravalle, Emilia-Romagna, Italy

![<p>Gehadad / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/Y9_2eJXEvMJ1ubnj3IUnrw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/102b0fb00f35c1cf926082cc385d2079)

Gehadad / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0]

What's more, the town’s fortification, a 19,000-square-foot (1,765sqm) bulwark set at an altitude of 1,312 feet (400m), played a central role in territorial feuds and battles against invaders and neighbouring fiefdoms until 1109 due to its strategic military position between Modena and Bologna.

Serravalle, Emilia-Romagna, Italy

![<p>Gehadad / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/htsCoWDrLvuJUkyio7AxLg--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/67b1902164fac65f33d2bec4689486ec)

Gehadad / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0]

The castle itself was vital to the protection of local land, farmers and tenants, and even reportedly played host to the legendary former Emperor Charlemagne while he was en route to Rome to be crowned in the 9th century.

Having played such a significant role in political and military history, not to mention having undergone numerous renovations over the centuries, the property also hides its fair share of architectural secrets.

Serravalle, Emilia-Romagna, Italy

![<p>AnetaMalinowska / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/B9sAD.Dh3ZmR.ioNSoh2OA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/c6613c182730f67f4c3f69d65aa96a25)

AnetaMalinowska / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0]

In addition to its castle, hunting lodge and four-storey lookout tower, the village is also home to an underground passage that connects the 18th-century palace to a nearby tower.

Whether the passage was built as an escape route or a means of secret defence is unclear, but it is believed that the tunnel is occupied by the ghosts of the numerous wives murdered by one Boccadiferro lord. Intrigued? Serravalle was last on the market for just under €2 million, or £840k million ($110k).