Can the spectacular architecture and interiors generated by AI exist in the real world?

One of the first AI images to enter the public consciousness (entirely for the wrong reasons) was a surreal, nightmarish vision in which dogs’ eyes and heads blend in impossibly grotesque nebulae. The year was 2015, and Google had just released the image, created

by its generative-AI tool, Deep Dream.

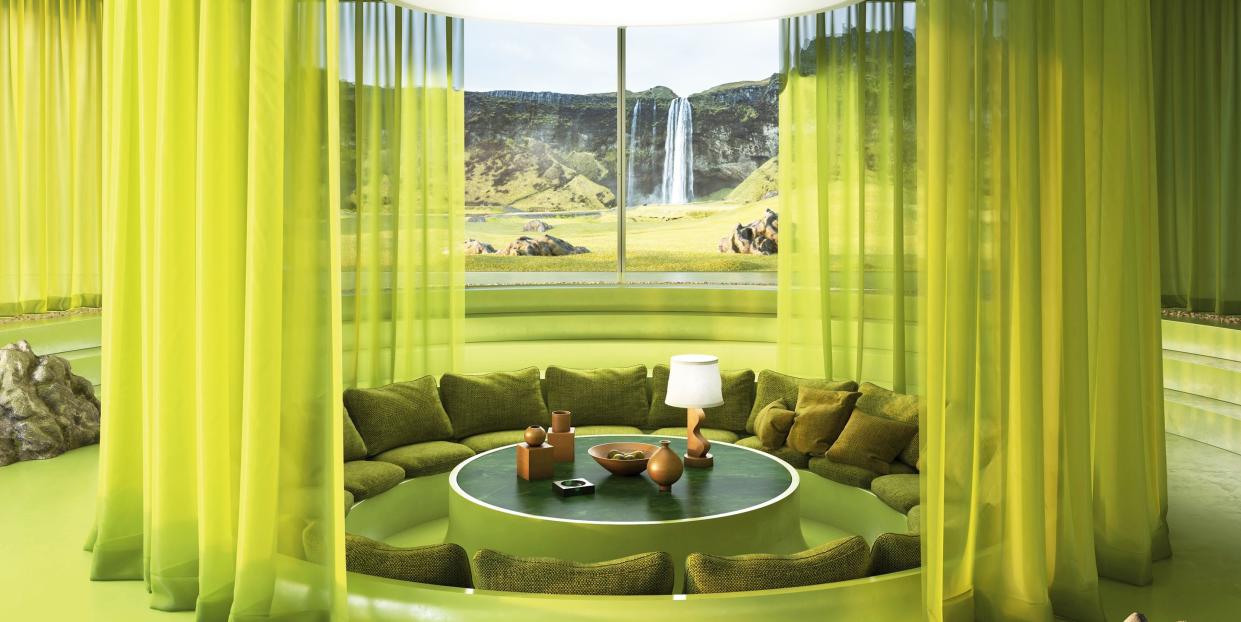

Now, almost a decade later, Dall-E, Midjourney or Stable Diffusion, in conjunction with their human prompt-writers, can create convincing images of just about anything – from award-winning ‘photography’ to magazine cover-worthy interiors and utopian cityscapes.

No stylistic reference is too geeky, no design movement too obscure and no mash-up is impossible, but where does this leave architects and designers? Last year, the architect and illustrator Anna Gibbs was quoted as saying it is ‘natural for architects to feel uneasy about a tool that, at first glance, looks as though it may be moving its favourite mug onto your desk and parking its bottom on your chair’.

But not all architecture studios are sceptical. Last April, Zaha Hadid Architects’ director Patrik Schumacher admitted in an interview that the studio uses generative AI to iterate images and inspire design solutions. He explained how they utilise prompts and references to prior projects, then elaborate on what arises. ‘I feel very empowered by all this possibility,’ he added at the time.

Tim Fu, who left Zaha Hadid Architects to set up his own practice last year, has continued to work with AI tools, which, despite their promise, also have their limitations. ‘When we explore the creative nature of AI, we tend to let the machine hallucinate to its heart’s content,’ he says, pointing out that the resulting images still require ‘intense human involvement to make an idea work in its context’. Fu’s work may take him on flights of fancy, but he is also one of the pioneering designers making his theoretical work into reality – albeit, so far, on a smaller scale.

Working alongside the Italian manufacturer Mavimatt, Fu designed the ‘Chromatic’ chair. Resembling the space-age designs of Eero Aarnio, with a generous pinch of Italian radicalism, the resulting, semi-spherical product is as much a product of AI and advanced manufacturing skills as of Italian craftsmanship, combining a carbon and fibreglass ‘chassis’ with leather upholstery. Fu’s ‘AI Stone Columns’, a series of stone capitals (the decorative top of a column) inspired by the swooping curves of parametric architecture, was conceived in Midjourney and translated into usable blueprints before being carved by stonemason Till Apfel.

‘When AI takes over parts of the design side, perhaps humans can re-input artistry into the fabrication,’ muses Fu. ‘It is ultimately up to us to decide where human artistry remains valuable when machines take over more roles.’

Juul van den Heuvel, a graduate of Design Academy Eindhoven, worked with Dall-E 4 and Midjourney to develop his thesis, ‘(A)I Designed a Chair’, which he showed at last year’s Dutch Design Week. ‘When I was working on my project, AI couldn’t yet analyse images,’ van den Heuvel explains, pointing out that he had generated over 500 images of chairs, gradually refining his prompt before choosing one that he felt best demonstrated the design process. ‘I wanted to tell the story of AI design – that’s why I chose this weird-looking chair,’ he explains. His unusual design features a double back on an asymmetrical oval base, rendered in a uniform ultramarine hue.

The product did reveal a limitation of generative AI, though. Van den Heuvel had only a single image of his final design to work with, because Midjourney could not (yet) provide accurate drawings with dimensions and side or top views. ‘(A)I Designed a Chair’ is meticulously constructed from 11 square metres of 4mm thick wood and weighs 20kg. This is not to say that it could not eventually be adapted to more advanced modes of production. Van den Heuvel was satisfied with the outcome, as the chair triggered a conversation about the potential role of AI in furniture design. ‘As designers, it’s our duty to explore new technologies,’ he concludes.

2023 may have been the year that generative AI hit mainstream consciousness, but designers’ interest in its possibilities predates the headlines warning of its potential perils.

Philippe Starck’s ‘A.I.’ chair for Kartell, launched at the 2019 Salone del Mobile in Milan, resulted from questions (‘How can you support our body with the least amount of material and energy possible?’) the designer put to Autodesk’s AI tool. Meanwhile, Carlos Bañon, architect, designer and assistant professor of sustainable design at the Singapore University of Technology and Design, created the skeletal legs for the smooth marble slab of his 2021 ‘AI Table’ using a similar methodology. ‘The real game-changer,’ he says about advances in AI-image generation, ‘has been the iterative dialogues with AI – you need to learn how to talk, interact and transfer information.’

Bañon’s first major generative AI work was a series of beguiling, monolithic staircases that seem to flow and twist between different levels. The pictures went viral and received over 850,000 likes on Instagram. The resulting exposure attracted a client in the UK, and Bañon is collaborating with another artist and exploring how large-scale CNC machines could make this dream interior a reality. His current AI work explores seating options in the shape of flowers. Translucent, organic and ethereal, ‘Blossom’ seating showcases the endless variations on a theme that AI tools can generate. Bañon intends to present a working, 3D-printed prototype to Singaporean authorities. If all goes according to plan, parks across the forward-looking city-state could soon feature these designs.

Bañon’s work is testament to the potential for social ‘likes’ to be turned into real-world commissions. For Argentine digital artist and designer Andrés Reisinger, ‘it is possible and perhaps necessary to create digital demand before presenting physical offerings,’ and he cites the vast costs and wastefulness involved in creating new products that might not sell. His own ‘Hortensia’ chair, inspired by hydrangea flowers, started life as a viral NFT artwork in 2018 before he and textile artist Júlia Esqué translated the design into a real chair produced by Moooi in 2022.

Reisinger has integrated AI into his design process, and now uses it, he says, to ‘help the unconscious to reveal itself’. His latest speculative series, ‘Takeovers’, is another viral hit on Instagram. It imagines dusky pink fabrics (some smooth, some wildly fuzzy) draped over uncannily familiar streetscapes. While these visions might not translate as readily into reality (a recent attempt in Miami fell rather flat), they challenge established notions of what an urban environment can be.

This disruption of expectations is exactly why the Milan-based architect and interior designer Hannes Peer sees AI as a valuable tool. His work had veered into the conceptual even before the rise of AI. The 2016 ‘Marmor’ project imagined living spaces constructed within an abandoned marble quarry, and it struck a chord upon its publication – Peer’s studio was inundated with requests to purchase apartments within the fictional scheme. ‘Crafting imaginative spaces,’ he says, ‘prevents us from falling into a mere aesthetic trial-and-error process driven solely by Instagrammable preferences.’ For Peer, AI-generated imagery lacks a level of sophistication that physical spaces can possess (the images are impossibly smooth, with a lack of the imperfections and patina that make a space special). For him, AI remains an imperfect tool to be harnessed, rather than a source of design ideas.

Perhaps surprisingly, the London-based digital artist, art director and designer Charlotte Taylor, who last year launched Design Dreams, a book dedicated to virtual interiors, takes a similar attitude to relying on generative AI. Her practice, Maison de Sable, has a portfolio of imaging work, including glass villas floating in the jungle, cave-like dwellings on the Med and even hotels on Mars. However, now that she’s making strides into the physical realm (projects include a listening bar in London and houses for private clients in Puglia and Andalusia), she harks back to her experience of designing architectural installations at university, when she drew on the floor with chalk and tried to imagine what the spaces would feel like. ‘I still design in a very tactile way and always have multiple tape measures spread out on my floor while drawing plans,’ she explains.

Whether you’re excited or concerned by the hype, it’s clear that AI is more than just a flavour of the month. For now, it seems unlikely it will fully replace designers and craftspeople whose guidance and input is still essential to the process. Instead, it is perhaps best seen as a springboard for inspiration and a tool for visualising novel spaces and products, aiding creatives to design further outside of the box than ever before.