Robber barons: explore the iconic mansions of America's first millionaires

The opulent estates of the richest Americans

![<p>Unknown author / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain] ; ZakZeinert / Shutterstock</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/BZQLaW29AJRi8OMvNklLfA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/ae17b0b11e58945cea068f89123f3844)

Unknown author / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain] ; ZakZeinert / Shutterstock

As American industrialism boomed at the close of the 19th century, so dawned the Gilded Age of wealth and opulence for the American elite.

However, even as their fortunes skyrocketed, capitalist tycoons still found themselves barred from many social hubs, which remained exclusive enclaves for the ‘old money’ set. Thus challenged, many of these American millionaires set about buying their way into high society by building their own hallowed halls, flaunting their fortunes through some of the most opulent estates in the Western world.

Read on to see inside some of these stately haunts...

The "nouveau riche"

Science History Images / Alamy Stock Photo

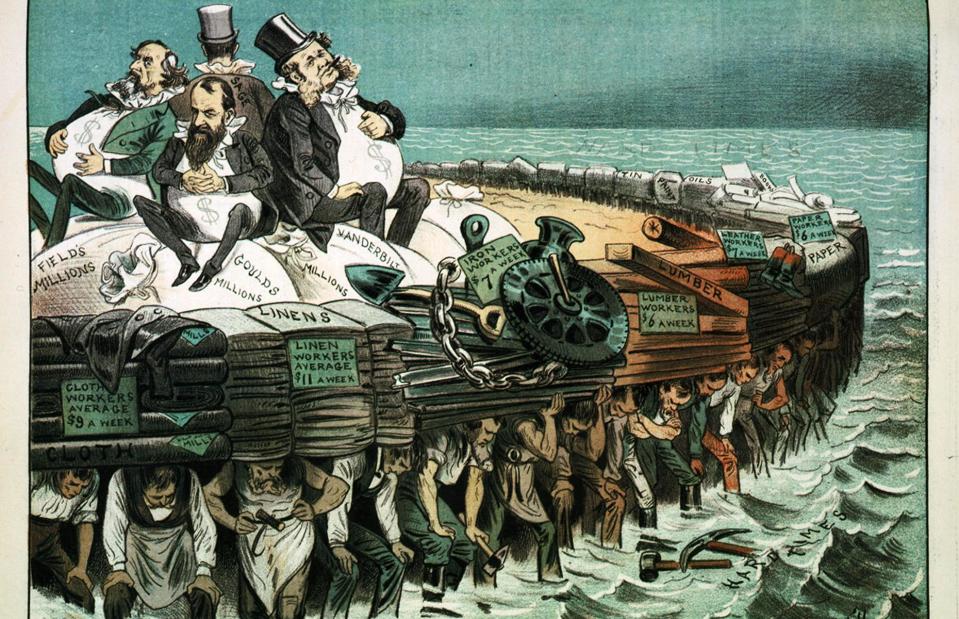

However, shaking off the mantle of "nouveau riche" was no easy task for these early industrialists, as their money was considered distasteful for more than the mere recentness of its acquisition.

The purportedly ruthless, exploitative and even corrupt business practices of tycoons such as Cornelius Vanderbilt, J P Morgan, and John D Rockefeller underwent much public scrutiny, aided and abetted by hostile political cartoons which depicted the businessmen as villainous caricatures.

Who were the robber barons?

GRANGER - Historical Picture Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

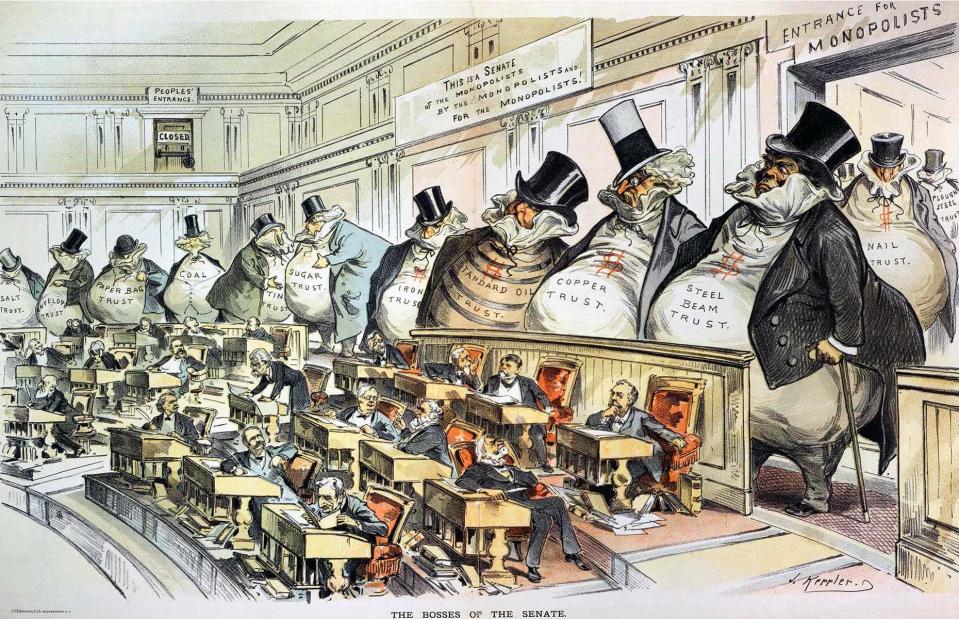

The term "robber baron", first coined by The New York Times in an 1859 article to describe Cornelius Vanderbilt, immediately captured the public imagination, conjuring up images of backroom government deals and mammoth financial monopolies.

As the phrase entered into common parlance, Vanderbilt and his financial compatriots began the uphill battle of buying their way back into society’s good books, brick by marble brick.

Let's explore some of the magnificent homes they built…

Cornelius "the Commodore" Vanderbilt

![<p>Mathew Brady's studio / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/XcrbvECYadIwwlgSAS.V3w--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/09f1a40ad64ea0502fe48793761592e3)

Mathew Brady's studio / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]

Any exploration of robber baron property must rightly begin with Cornelius “the Commodore” Vanderbilt, the man who started it all. Vanderbilt was an early investor in the railroad industry, and by the 1850s was the wealthiest man in America.

With a leadership position in the inland water trade, enormous shipping holdings and his substantial stake in the rapidly expanding railway system, Vanderbilt amassed a net worth of more than $100 million – roughly $3 billion (£2.3bn) in today’s money – by the time of his death in 1877.

Cornelius II

Maidun Collection / Alamy Stock Photo

After Vanderbilt’s death, his vast fortune trickled down his family tree to his children and grandchildren, creating an entire family of millionaires. The lion’s share of the Commodore’s estate was inherited by his eldest son, William Henry, who managed to double his $100 million inheritance through his business pursuits before his own death eight years later.

The majority of his fortune was then divided between his two eldest sons, Cornelius II, pictured here, and William, who would turn it into some truly spectacular homes.

Cornelius Vanderbilt II House: prime location

![<p>Unknown author / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/R9fXCG0nUmI9zvbAbt3Z_A--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/e8a9e9d810a59cc9013408e7c95ebdba)

Unknown author / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]

Cornelius Vanderbilt II, widely acknowledged to be the patriarch's favourite child, set his sights on building the largest and most opulent home in New York City.

From its vantage point on the coveted northwest corner of 5th Avenue and West 57th Street – a location which first required the purchasing and subsequent demolishing of three extant brownstones – the new home was designed to command attention, as well as to “dwarf” the Petit Chateau designed by sister-in-law Alva Vanderbilt, with whom Cornelius’ wife Alice was in steep competition.

Cornelius Vanderbilt II House: Beaux-Arts design

Public domain

Cornelius hired the celebrated Beaux-Arts architect George B Post to design the townhouse, which was commissioned as a showstopping, chateaux-inspired residence of red brick and limestone.

After the house’s completion in 1883, Cornelius went on to hire the finest artisans money could buy to decorate the interiors. Aware of the family’s precarious social position, Alice even went so far as to commission the creation of a family coat of arms, which was carved in stone above the entryway to the home.

Cornelius Vanderbilt II House: expansion

Public domain

However, in order to retain their position as the owners of the most imposing residence on 5th Avenue in light of larger robber baron mansions springing up around them, Cornelius and Alice commissioned an expansion of the house from Post and rising architectural star Richard Morris Hunt in the early 1890s.

Cornelius hired extra builders to work day and night to finish the expansion, which was completed in record time by 1893, and cost the modern-day equivalent of $102 million (£79m).

The Breakers: Rhode Island estate

![<p>UpstateNYer / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/JjYCskNefCIXlt8vp_lxNQ--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/c69dfc2b778a829cd0e5aab373d408ec)

UpstateNYer / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0]

Despite its 130 rooms – including an enormous ballroom and Louis XV and Louis XVI-style salons – Cornelius and Alice were not satisfied with their expanded New York home and decided to chase the city’s elite out to Newport, Rhode Island where they purchased The Breakers for roughly $15 million (£11.7m) in today's money.

Unfortunately for the couple, the Queen Anne-style summer “cottage” burned down in 1892, necessitating a complete rebuild, but creating yet another opportunity for opulent construction.

The Breakers: Renaissance style

![<p>xiquinhosilva / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 2.0]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/ALAF4oafQA6guZ6ine5YOg--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/967daba45869fb91813543510f871950)

xiquinhosilva / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 2.0]

Cornelius and Alice re-hired Richard Morris Hunt to design the new Breakers, this time reimagined as a five-storey, Renaissance-style Italian palazzo. With no expense spared, the new cottage was finished in 1895 with an estimated final budget of at least $255 million (£199m) in today’s money.

Richly appointed by Jules Allard and Sons and Beaux-Arts architect and interior decorator Ogden Codman Jr, the mansion’s 70 rooms overflowed with premium marble, gilded fixtures and furnishings imported from French chateaux.

The Breakers: the grandest "cottage" in Newport

![<p>xiquinhosilva / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 2.0]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/Win9k6jOtEKoeFuYpd04Xg--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/96f83d385ce2547667847522b409d9f4)

xiquinhosilva / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 2.0]

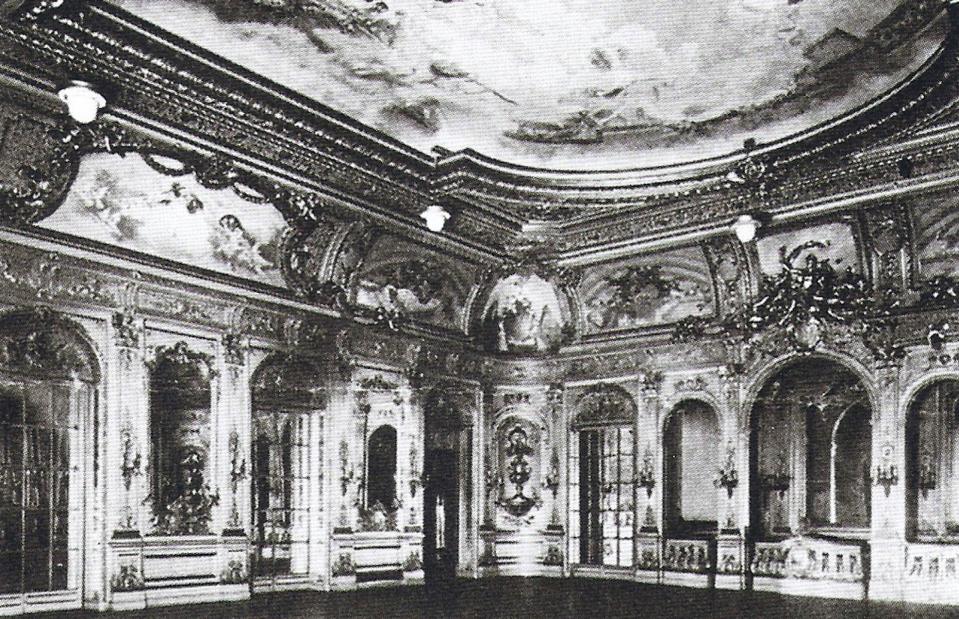

The final product was far and away the most opulent of the Newport summer cottages, outshining Alva Vanderbilt’s Marble House and attracting extensive interest from the elite enclave’s other residents.

Just as Alice had hoped when commissioning the home, many of Newport’s finest families accepted her invitations to grand balls and soirées merely to get a peek inside the magnificent house, and to marvel at its marble staircases, platinum leaf walls and enormous crystal chandeliers.

George Washington Vanderbilt II

![<p>Unknown author / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/Qh0wrWETpbIyqFBSM3tHdw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/d58b8e7116279471c4de4b7001ab0125)

Unknown author / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]

Not to be outdone by his older brothers, William Henry’s youngest son, George Washington Vanderbilt II, went on to commission the largest and grandest private estate in the US – Biltmore.

Though his own inheritance from William Henry was less substantial than that of his brothers, George still inherited millions after his father’s passing, and in 1889 he hired over 1,000 workers to begin construction on an enormous 178,926-square-foot (16,622sqm) residence. According to reports it cost $6 million (£4.7m) to build, which is around $200 million (£156m) in today's money.

Biltmore: colossal residence

ZakZeinert / Shutterstock

George called upon the family-favourite architect William Morris Hunt, to design the colossal residence in the scenic countryside of Asheville North Carolina, which he planned to name after the Dutch town of De Bilt, where the Vanderbilt family had its roots.

The 250-room mansion was to be modelled after French Chateaux, and would preside over 700 parcels of land totalling 250,000 acres (101ha).

Biltmore: failure to impress

Harvey Meston / Archive Photos / Getty Images

After its completion in 1895, George, who was a great art collector, packed the home with furnishings, paintings and antiquities dating as far back as the 15th century.

However, rather than appealing to the upper echelons of society, the home’s grandeur was instead deemed flashy, tacky and tasteless by such social critics as Edith Wharton and Caroline Astor, who believed that the opulent mansion epitomised the classlessness of the "nouveau riche".

Biltmore: dark secrets

![<p>Warren LeMay from Cincinnati, OH, United States / Wikimedia Commons [CC0]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/eOhgEpdZ1Hh_bQVh9aG5VA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/a7a82ba7cfdaa432ba375f778fbb7283)

Warren LeMay from Cincinnati, OH, United States / Wikimedia Commons [CC0]

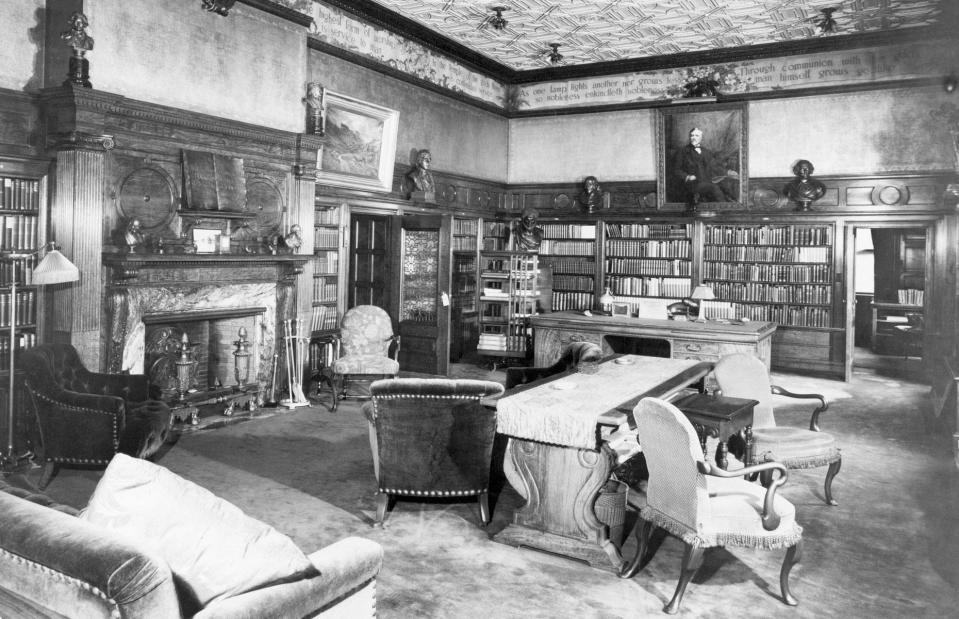

Not only did the enormous home fail to impress the societal doyens it was designed to entice, but the mansion hid a macabre side as well. After George died in 1914, his wife Edith was supposed to have spent hours in the library every day, speaking to her deceased husband.

The home is also packed with secret doors and passageways, as well as an unexplained space filled with mannequins!

Andrew Carnegie

![<p>Theodore C. Marceau - Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/yOvMwGCdCCZbb9SeL_VELg--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/2af98405430f0b42ad2abc04ab71ca45)

Theodore C. Marceau - Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]

Originally born in Dunfermline, Scotland in 1835, Andrew Carnegie had risen to fame and fortune in the United States by the turn of the century. Having spearheaded the expansion of the American steel industry, Carnegie accrued a fortune which would have equated to hundreds of billions of dollars in today’s money.

A philanthropist as well as an industrialist, Carnegie gave away nearly 90% of his fortune in the final 18 years of his life to various charities, foundations, and universities, and called upon others to do the same.

Andrew Carnegie Mansion: "humble" home

![<p>Unknown artist - Catalog Photo / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/dnt2cbR9lCmiO0DeTzSYJw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/dba6c56e11dde096555bff27e811e4d0)

Unknown artist - Catalog Photo / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]

Carnegie’s real estate holdings mirrored his preachings, and despite his immense wealth, he asked architectural firm Babb, Cook & Willard to design for him the “most modest, plainest and most roomy house in New York".

The home would be located not on the fashionable stretch of Fifth Avenue, where so many of his peers had built their palaces, but on a 1.3-acre (0.5ha) lot about a mile north of the desirable area.

Andrew Carnegie Mansion: grander than planned

Bettmann / Getty Images

The Georgian revival-style home was completed in 1902, and was ultimately a bit grander than Carnegie had specified, with 64 rooms spread across 56,364 square feet (5,236sqm).

These rooms were all comfortably appointed in accordance with early 20th-century standards, and featured details including carved wall panels, decorative ceiling mouldings, gilt fixtures and antique furnishings. The home also offered a private garden, the largest in New York, which Carnegie cited as the reason he selected the acreage despite its less-than-fashionable location.

Andrew Carnegie Mansion: modern technology

![<p>Unknown author / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/yG5oSOfcRThg7wI5BlhUig--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/725886211cb9d2e9b6e4aa791846affa)

Unknown author / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]

In addition to its creature comforts, the home also boasted the best in modern technology. It was the first residence in America to be built from a steel frame, and one of the first to feature an Otis lift and central heating.

The mansion served as Carnegie’s primary residence until his death in 1919, at which point his wife Louise continued to live there until her own passing in 1946. The house subsequently passed to the Carnegie Foundation, and was ultimately gifted to the Smithsonian in 1972.

Thomas Carnegie

![<p>Smith, Percy F / Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/HV9G7oV5Kc671YFaFJ.UtQ--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/17f3d8ace6ab85c0732a89bdc1216e9f)

Smith, Percy F / Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain]

Though the lesser known of the Carnegie brothers, Thomas Carnegie was a steel industrialist in his own right, and the co-founder of the Edgar Thomson Steel Works. In 1881, Thomas purchased land on Cumberland Island in Georgia as a gift for his wife Lucy and their nine children, on which he commissioned the construction of an enormous mansion.

Dungeness: lavish estate

![<p>Philip E. Gardner, HABS photographer / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/gyVFXC.gXmIebTH3o9wqrw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/fcfe470a11c72c98e5acd523fdecc6e2)

Philip E. Gardner, HABS photographer / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]

The 59-room Dungeness, as the home would be called, was modelled after the turreted castles of Carnegie's native Scotland. The spectacular estate included multiple pools, a golf course and 40 auxiliary buildings to house the 200-odd servants required to keep a mansion of that size operational.

Between 1881 and 1886, Carnegie continued to buy up land on Cumberland Island to expand the estate, which had yet to be finished to his satisfaction before his sudden death in 1886.

Dungeness: tragic ending

Abandoned Southeast

Thomas’ wife Lucy finished the house’s construction herself, and turned Dungeness into the family’s primary home until her own death in 1916. Lucy’s estate was sufficient to maintain the property until the financial crash of 1929, at which point the Carnegie family was forced to abandon the mansion forever.

Dungeness: Mysterious fire

Abandoned Southeast

30 years later, a mysterious fire broke out at Dungeness, destroying the house and the majority of the auxiliary buildings, leaving behind only haunting ruins of what had once been a magnificent European-inspired mansion.

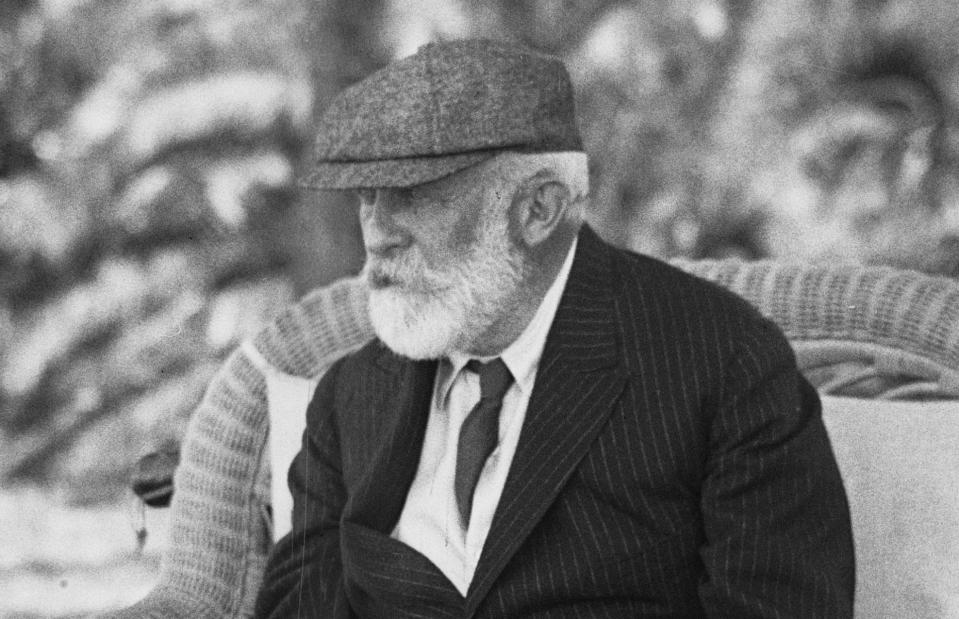

John D Rockefeller

![<p>Oscar White / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/WzhPUivYnrBLC.IhWp3hkw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/20665d0ea2fbe588f4eecfbc4145f8d3)

Oscar White / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]

Giving Carnegie a run for his money, so to speak, business magnate John D Rockefeller was also widely considered the wealthiest American of all time. With substantial shares in the Standard Oil Company, which he founded, Rockefeller quickly established a monopoly on the industry, revolutionising the petroleum trade in America.

As the importance of kerosene and gasoline skyrocketed with the spread of electricity and the invention of the automobile, Rockefeller rose to become America’s first billionaire, with a peak net worth of approximately $28 billion (£22bn) in today’s money.

Kykuit: Georgian Revival architecture

365 Focus Photography / Shutterstock

In 1893, Rockefeller purchased land in the Pocantico Hills of New York, near his brother’s estate and commissioned the construction of a massive mansion which would overlook the Hudson River. Kykuit, as the home came to be known, was originally designed to be a steep-roofed, three-storey structure.

However, the final product was redesigned by celebrated architect William Welles Bosworth to be an imposing six-storey stone Georgian Revival structure, as can be seen here.

Kykuit: finest furnishings

![<p>Ɱ / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/kKWKOiPV3FmtG2tevoMQkA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/d05a9ddd53d518fdb30e6647ede3068b)

Ɱ / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0]

Rockefeller next hired popular interior designer Ogden Codman Jr to decorate the home, sparing no expense on the elegant neo-classical furnishings which enjoyed a vogue in the early 20th century.

After six years of construction, the home was finally finished in 1913, and packed to the gills with antique English furniture, Chinese and European fine ceramics and a few Ming Dynasty pieces specially purchased from J P Morgan’s private collection.

Kykuit: the family seat

Felix Lipov / Shutterstock

In addition to the magnificent 40-room mansion, Rockefeller also equipped his estate with a private golf course, expertly manicured gardens and lawns and a coach barn packed with his collection of cars and carriages.

Kykuit went on to serve as the family seat for four generations of Rockefellers, each of whom added to its prestige by continuing to fill it with valuable antiques, artworks and curios from around the world.

Henry Clay Frick

Bettmann / Getty Images

Though perhaps less of a household name than Carnegie or Rockefeller, Henry Clay Frick amassed a fortune equal to any of the robber barons through his work in the coal and steel industries.

Like many of his fellow industrialists, Frick purchased land on New York City’s fashionable Fifth Avenue and went on to commission the construction of what was contemporaneously described as the most expensive and most sumptuous house in America. The home and land would equate to around $155 million (£121m) in today’s money,

Henry Clay Frick House: tasteful style

Courtesy of The Frick Collection / Frick Art Reference Library Archives

Frick appointed the firm of Carrère and Hastings to design his three-storey mansion in the popular Beaux-Arts style, specifying that the home should be “in good taste, not ostentatious".

The result was a simplistic but elegant limestone mansion, large but not lavish in its exterior design. The 61-room house was completed in 1913, at which point Clay, an inveterate art lover, set about stocking its interiors with his impressive collections.

Henry Clay Frick House: unparalleled art collection

Courtesy of The Frick Collection / Frick Art Reference Library Archives

These included Renaissance and Rococo furniture, Meissen and Sèvres porcelain, Limoges enamels and, most notably, one of the finest privately held collections of paintings in the world, including works by Holbein, Vermeer, Goya and Fragonard.

Frick even went so far as to commission an entire Rococo-style room in which to display a series of Fragonard panels as they were originally intended to be presented.

Henry Clay Frick House: generous bequest

Courtesy of The Frick Collection / Frick Art Reference Library Archives

However, the most impressive rooms in the home were the East and West Galleries, each topped with concave glass ceilings and intricately carved cornices.

Tragically, Frick only lived in the property for five years before his death in 1919. In his will, the industrialist tycoon gifted the home and its entire contents, art collection included, to the American people, along with a $15 million (£12m) endowment to fund the eponymous art museum, which opened in 1935.

John Jacob Astor

Painting / Alamy Stock Photo

One of the earliest businessmen to achieve the title of "robber baron", John Jacob Astor was a German-born merchant and real estate mogul whose fortune arose from a combination of his monopoly over the fur trade, his operations smuggling opium into America from China and his early investments in real estate in and around the rapidly developing New York City.

One of the wealthiest people in modern history, Astor left a legacy of riches which would bolster the financial and social careers of several generations to come.

Mrs. Caroline Astor

Zip Lexing / Alamy Stock Photo

One of Astor’s most prominent descendants (by marriage) was the Gilded Age society doyenne Caroline Webster Schermerhorn Astor, leader of New York City society’s infamous "Four Hundred", and matriarch of the male line of American Astors.

The Mrs Astor, as she preferred to be known, married William Backhouse Astor Jr, John Jacob Astor’s grandson, and went on to build a substantial reputation in her own right as a hostess, socialite and self-proclaimed "gatekeeper" to New York City’s high society.

Beechwood: Italianate mansion

Joseph Sohm / Shutterstock

In 1881, William Backhouse Astor Jr splashed out $190,000 (£148k) – almost certainly at the behest of his wife – to purchase the Italianate Beechwood mansion in Newport, Rhode Island.

The couple spent a further $2 million (£1.6m) renovating the 39-room home, turning it into a glittering palace suitable for hosting elaborate summer parties for all of Caroline’s high-society friends. An invite to the ocean-front property soon became the most coveted ticket in town.

Beechwood: statement of wealth

![<p>Beyond My Ken / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY SA-4.0]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/CBxmwpHiGvQpmrOAklEIfg--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/26e1ad893abca7d1f8d3b5f74182bf09)

Beyond My Ken / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY SA-4.0]

With parquet floors, glittering chandeliers and gold moulding inspired by Versailles, the magnificent mansion was as much a statement of wealth and power as any home decorated by the Vanderbilts.

After William Backhouse’s passing, Beechwood was inherited by his son, John Jacob Astor IV, who married his wife Madeleine in the ballroom but died in the sinking of the Titanic in 1912. Madeleine continued to live at Beechwood until her own death in 1940.

Beechwood: theatre company

Felix Lipov / Alamy Stock Photo

The mansion then passed through a series of owners until 1981, when it was bought by Paul M Madden, a recent graduate of the National Film and Television School in the United Kingdom.

Madden reinvented the house as a tourist attraction, launching the Beechwood Theatre Company in conjunction with the University of Rhode Island History and Drama Departments, which conducted live theatrical tours hosted by actors portraying members of the Astors’ staff circa the 1890s. In 2010, the mansion was purchased for $10.5 million (£8.2m) by Larry Ellison.

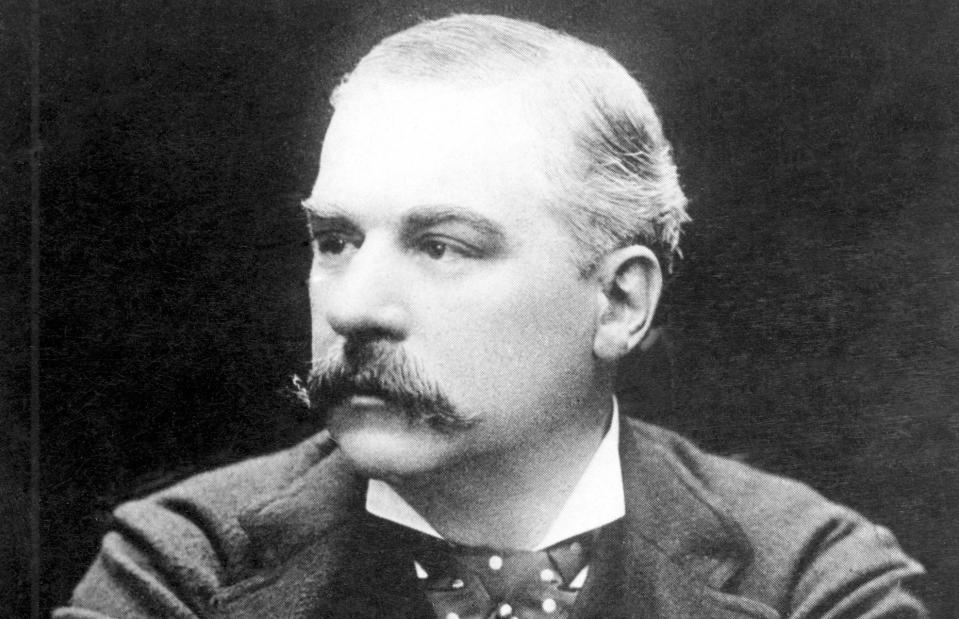

J P Morgan

Smith Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

Wall Street titan and investing tycoon J P Morgan dominated the corporate world of the Gilded Age. As the driving force behind a wave of industrial consolidation, Morgan was credited with shepherding the American financial world out of the "Panic of 1907", and was hailed for much of his career as the lynchpin of the American economy.

By the time of his death at the age of 75, Morgan had amassed an estimated fortune of $80 million – the equivalent of $2.5 billion (£1.9bn) in today’s money.

Denham Place: a Georgian marvel

Beauchamp Estates / YouTube

With a penchant for luxurious living, J P Morgan possessed an expansive property portfolio which spanned both sides of the Atlantic. The American tycoon was a true Anglophile, and the purchase of this Buckinghamshire estate in England enabled him to add his name to an illustrious list of previous owners, including the Bonaparte family and the High Sheriff of Buckinghamshire, to name but a few.

The magnificent late-17th-century Denham Place mansion, as shown in this YouTube tour, was last on the market for $94 million (£75m). It boasts a magnificent Georgian façade and 43 acres (17ha) of sprawling parkland designed by renowned 18th-century landscape architect Lancelot "Capability" Brown.

Denham Place: entertaining space

Beauchamp Estates / YouTube

The Grade I-listed manor house comprises a jaw-dropping 28,500 square feet (2,648sqm) of space, including 12 reception rooms, 12 bedroom suites, 14 bathrooms, family and catering kitchens, a private chapel, two staircases and an elevator.

As Morgan was a renowned art collector, the home is unsurprisingly well stocked with hand-painted ceiling frescos, custom crystal chandeliers, silk wall panels and curtains and even a handwoven carpet inspired by one in Buckingham Palace.

Denham Place: designed to impress

incamerastock / Alamy Stock Photo

Amply proportioned for hosting, the mansion also boasts a number of special features designed specifically for entertaining, including a theatre and formal dining room with an Italian Calacatta marble fireplace.

Morgan, like many of his Gilded Age peers, was much celebrated for his elaborate parties and events, and a stately home of this size and grandeur would have provided him with an ideal platform on which to stage some truly lavish gatherings.

The Morgan brownstones: family homes

Everett Collection Historical / Alamy Stock Photo

Like all the best families in Gilded Age New York society, Morgan also owned an impressive 45-room brownstone on Madison Avenue, which he bought for his son Jack in 1904. The home served as the family’s homestead until Jack's death in 1943. It was then sold to the Lutheran Church in America to serve as its headquarters.

In addition, Morgan also owned 219 Madison Avenue, the southernmost brownstone on the corner of Madison Avenue and 36th Street, which he bought in 1881 as his own New York residence. He then purchased the central brownstone in 1903, which was then razed to make space for a garden.

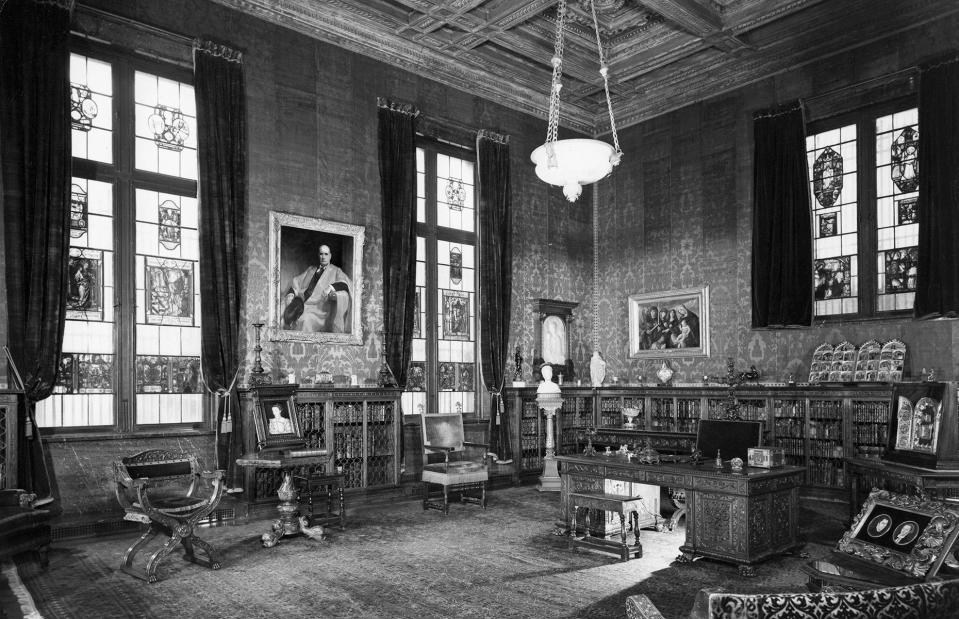

The Morgan Library: an overflowing library

Smith Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

However, Morgan’s real ‘home’ was not the stylish brownstone, but rather an address further down Madison Avenue – the prolific Morgan Library, or ‘the Morgan’, as it came to be known colloquially.

Morgan set about designing a residence to house his growing collection of rare manuscripts, which would no longer fit in his home. With the help of architects McKim, Mead, and White, he transformed it into his Italian Renaissance-style library between 1902 and 1906.

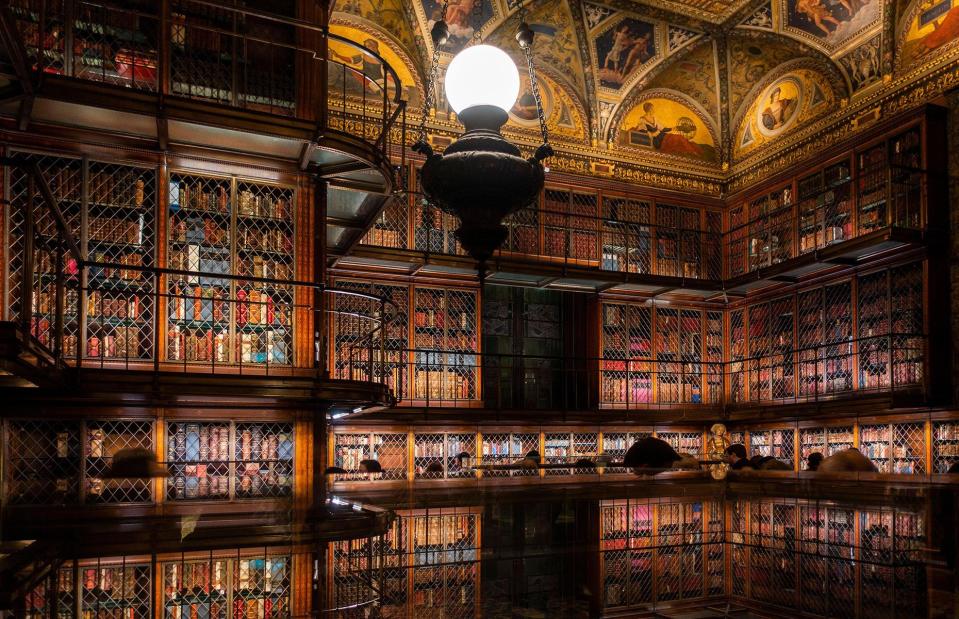

The Morgan Library: a lasting legacy

Randy Duchaine / Alamy Stock Photo

The library was accordingly packed to the gills with Morgan’s collection of rare manuscripts, artworks, and other antiquities.

After Morgan’s passing, the library was made a public institution in 1924 by Morgan’s son Jack in accordance with his father’s wishes, and extensions were added in 1928, 1962, and 1991. Today, the library and its treasures remain accessible to the public.