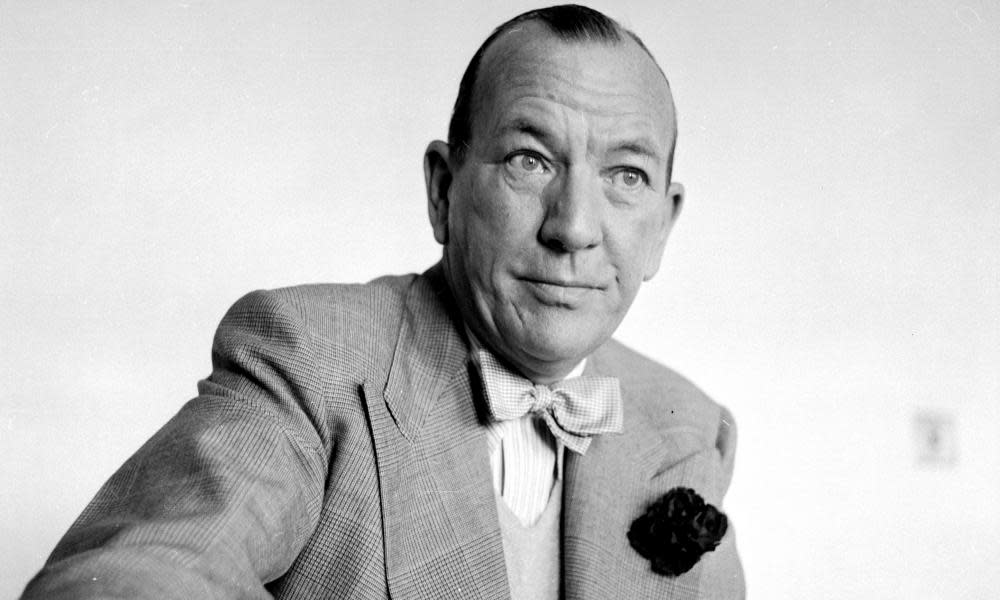

Revealed: Noël Coward’s unseen plays aimed to deal with homosexuality

Noël Coward worked on two plays that openly featured same-sex relationships at a time when homosexuality was still illegal in England, and strict censorship laws governed theatres, new research reveals.

The master playwright was planning to write about a homosexual triangle in one play and to confront homophobic prejudice in another, according to an unpublished letter of 1960 and an unknown scene for an unfinished 1967 drama.

The discoveries have been made by Russell Jackson, emeritus professor of drama at the University of Birmingham, who told the Observer: “I was surprised to find this evidence that Coward wanted to deal more frankly with homosexuality than he had ever been able to before in a play.”

It was not until 1967 that the Sexual Offences Act decriminalised private homosexual acts between men in England and Wales aged 21 and over, and 1968 when the Theatres Act repealed a law that had enabled the Lord Chamberlain’s Office to censor or ban any play.

Under the Licensing Act of 1737 and the Theatres Act of 1843, it had been a legal requirement for all plays intended for public performance to be submitted to the Lord Chamberlain’s Office for licensing. Plays deemed indecent or offensive could be rejected or censored, although by the end of the 1950s, playwrights sensed new freedoms.

Jackson said: “As a gay man, Coward exercised discretion in his public persona. And as a playwright, until the last decade of his career, he was constrained by the theatrical censorship of the Lord Chamberlain’s Office from directly addressing homosexuality.”

He continued: “A number of Coward’s published and performed plays had included identifiably – if not explicitly – gay or lesbian characters. The emphasis in A Song at Twilight in 1966 would not be on the central character’s homosexuality in itself, but the subterfuges by which he had managed to pass as heterosexual.”

Coward, a playwright, actor and composer, died in 1973, aged 73. He was the son of an unsuccessful piano salesman and was raised as a working-class boy in the south-west London suburb of Teddington.

Making his name in 1924 with a serious play, The Vortex, about a drug-addicted son and dissolute mother, he became one of the foremost playwrights of the 20th century, best-known for classic comedies including Hay Fever, Blithe Spirit and Private Lives and as the co-writer of David Lean’s classic 1945 film, Brief Encounter.

The 1960 letter was written by his much-loved assistant Lorn Loraine, who had worked for him since the 1930s and whose opinions he greatly valued. It reveals that Coward had created a love triangle between three men – called Owen, Trevor and John – one of whom appears to be married.

“Darling master,” Loraine wrote, “I have thought a lot about this play outline and I feel strongly that [it] must be treated entirely psychologically and with restraint and no sign of melodrama.

“I have been wondering whether it would be a good idea for Trevor to have had an affair with Owen Fletcher but to be really, all the time, deeply and jealously in love with John – a love which John has never returned and which has therefore turned sour.”

Jackson said that in 1967 Coward started writing a play called Age Cannot Wither, some of which has been published: “But there’s a part of it that’s not – the second scene.”

It features Naomi, an independent-minded grandmother in her 60s who scolds her daughter-in-law, Melissa, over her inability to accept that Naomi’s grandson, Jasper, has left his wife to live with another man, an antiques dealer.

Naomi tells her to “behave with more dignity”, adding: “Please go away … and give your acids time to settle. I know you are genuinely distressed and upset and, in spite of what you say, I assure you that I have not the least desire to patronise you or insult you. As far as the Jasper situation is concerned there is nothing we can any of us do at the moment beyond keeping calm.

“I see clearly that you are much more shocked by it than I am but that perhaps can be accounted for by the difference in our generations. I have a feeling that only the very old or the very young are capable of understanding the social and moral values of these strange times.”

The unpublished material will feature in Jackson’s forthcoming book, Noël Coward: The Playwright’s Craft in a Changing Theatre, to be published later this month.

Jackson unearthed the unpublished material in researching the Coward archives, which are divided between London, where they are administered by the Noël Coward Archive Trust, and the Noël Coward Collection at Birmingham University’s Cadbury Research Library.

The holdings boast manuscript and typescript drafts and personal and professional correspondence, among “boxes and boxes” of material, Jackson said.

Alan Brodie of the Coward estate said: “We’re delighted that the archive continues to throw up surprises and that it shows just how, from The Vortex onwards, he wasn’t frightened to explore controversial [for the time] issues.”

Noël Coward: The Playwright’s Craft in a Changing Theatre is published on 19 May by Methuen Drama, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing.