Remembering the Trailblazing Black Supermodels of the 1970s

Bell bottoms, Watergate, "Star Wars", disco — the 1970s were as tumultuous as they were fabulous. And among the chaos and shifting cultural values were seeds of opportunity.

Marginalized people — namely the LGBTQ+ community, women and African Americans — began to carve out their own lanes in entertainment, beauty and, eventually, fashion. For Black models, this was finally the decade they would get to be center stage.

Sure, the '80s and '90s ushered in the greats we remember today, like Naomi Campbell, Iman, Tyra Banks, Veronica Webb and Alek Wek, who are heralded for breaking barriers (as they should be!). But the 1970s cracked the door open, thanks to a perfect storm of new ideas, daring designers and glamorous muses of all shades and backgrounds, the likes of which we haven't seen since. Where did this all begin? And where did it end?

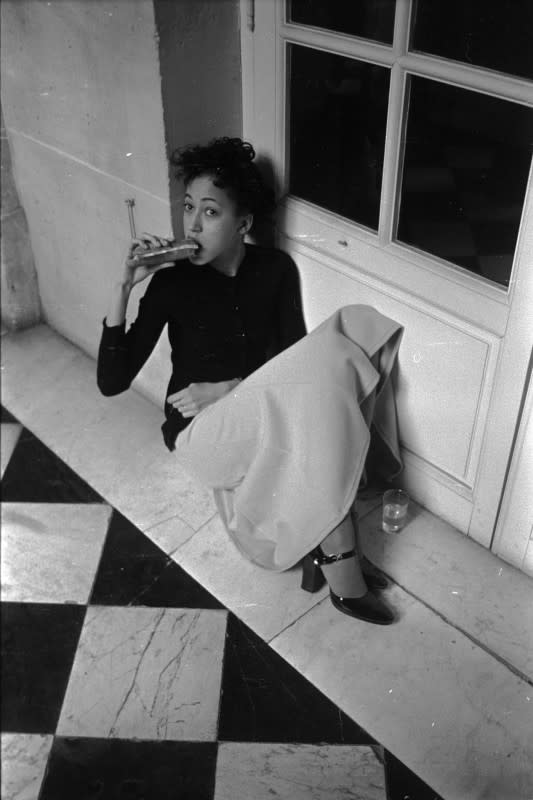

Black models of the '70s were part of a more significant cultural movement, but they were not the first. A small handful of Black women were scouted to work for European designers as early as 1955. Christian Dior, Pierre Balmain and Jacques Fath hired Dorothea Church as both a fit model and to appear in their haute couture presentations. Taking cues from her and fellow model pioneers Hellen Williams and Ophelia Devore (a mixed-race woman of African-American descent who passed for Norwegian in the '30s and '40s), young Black women from all over America began to make their way to Europe with the hopes of following in their footsteps.

Photo: Reginald Gray/WWD/Penske Media via Getty Images

One has to wonder why young, Black aspiring models were so willing to travel thousands of miles, leave behind their friends and family and move to a foreign country where they may not even speak the language. The answer is simple: racism.

"There was a movement of Black models [going to] Europe because they weren't finding opportunities here," says Taniqua Martin, a fashion historian and host of the "Black Fashion History" podcast. "Black models weren't being cast in shows or put on the cover of magazines [in America]."

Black Americans fleeing to Europe, away from the limitations of racism stateside, extends back to the early 20th century. More than a few Black GIs from World War I and II yearned to stay in France and other Western European countries after the war ended because of the respect and acceptance they experienced, often for the first time in their lives. Likewise, Black artists and creatives flocked to Paris in droves — Josephine Baker, Louis Armstrong, Nina Simone and James Baldwin all attributed their early success to European audiences.

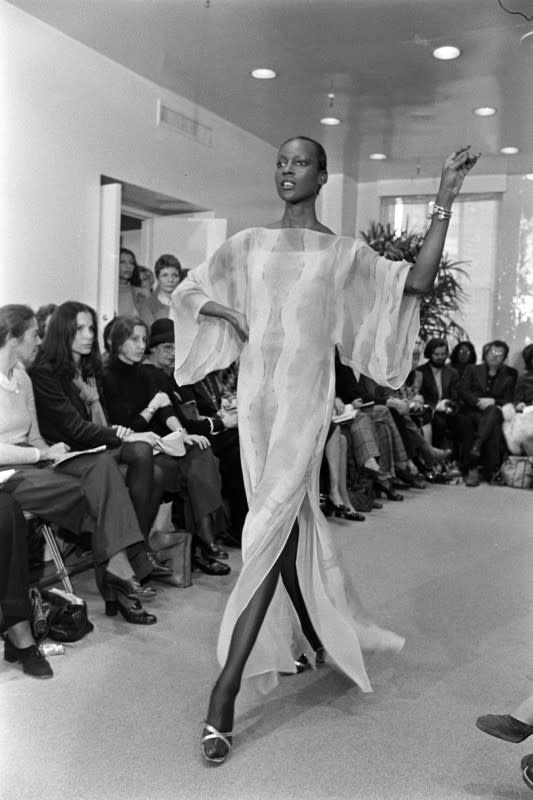

Photo: Reginald Gray/WWD/Penske Media via Getty Images

"I think of it as the second great migration," Martin remarks, referring to the Great Migration of the early 20th century, when African Americans moved in droves to the North, midwest and western states to escape the brutality of the Jim Crow-era south. In much the same way, Black models saw Europe as an opportunity to secure work —and they weren't wrong. Just look at the legendary Battle of Versailles in 1973, which introduced up-and-coming Black designers and models (such as icon Pat Cleveland, a Studio 54 favorite) to European society, which arguably could not have taken place in even the most liberal American cities at that time.

It wasn't just Europe's diverse opportunities that helped create the demand for Black models; Patrick Michael Hughes, fashion historian and associate professor at Parsons, notes that the influence of Black culture was unavoidable during that time. "There was a rise [in the popularity] of soul music and Blaxploitation films — everybody was doing 'Superfly' whether they acknowledged it or not."

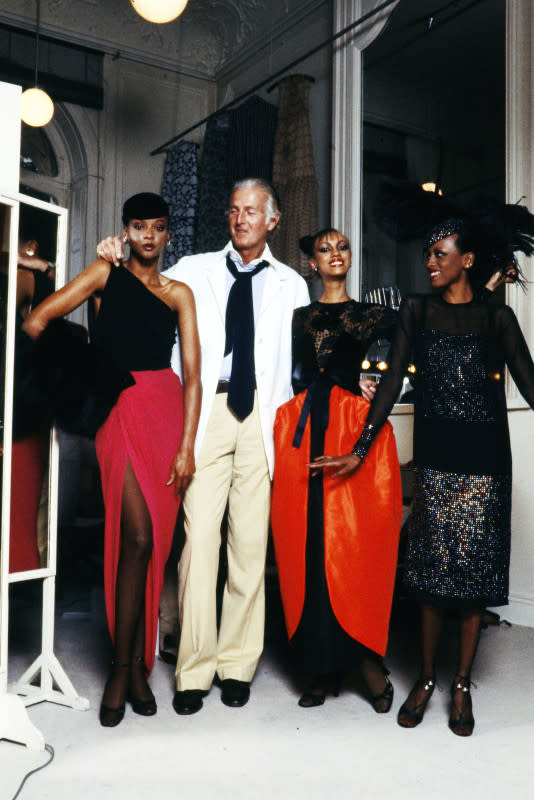

Photo: Guy Marineau/Penske Media via Getty Images

The coveted fashion of the 1970s were heavily modeled after the glamour of disco, which originated in underground Black and Brown LGBTQ+ dance clubs. Who better to emulate this aesthetic — glittery lycra jumpsuits, bronze satin gowns, flowing caftans with tribal motifs — than Black women? They (and the designers who hired them) wielded that influence across runways, in advertisements and, for the first time, on magazine covers.

There was Yves Saint Laurent and his muse, Martinique-born Mounia, and Hubert de Givenchy's Black Cabine, a group of house models he worked with consistently in the late '70s, including Carol Miles, Sandi Bass, Lynn Watts and Diane Washington. Paco Rabanne hired Black models for his runway shows as early as the mid '60s, a move that cost him dearly.

Photo: Guy Marineau/Penske Media via Getty Images

When Rabanne hired model Donyale Luna for his show, American fashion media spat in his face, and he was blackballed by the fashion elite for a decade. Luna is one of the most famous and tragic figures of this crop of trendsetters: Born Peggy Ann Freeman in Motor City in 1945, she was still a teenager when legendary fashion photographer Richard Avedon helped her set up shop in London; he was instrumental in netting the Detroit native the cover of British Vogue in 1966, the first Black woman to do so, and she went on to be featured in dozens of magazines. Still, until recently, her legacy remained fairly unknown.

Photo: PA Images via Getty Images

As far as Martin is concerned, this conversation must include another iconic model named Naomi — Naomi Sims, who's widely credited as one of the first Black supermodels. Mississippi-born Sims was the first Black model to sign with Wilhelmina Models — a feat, Martin believes, that was much more impressive due to Sims' skin tone.

"Darker-skin models had more difficulty [securing work] because they were visibly Black," she argues.

Photo: WWD/Penske Media via Getty Images

Even before the '70s, Sims established herself as a highly sought-after commercial model, starring in a national AT&T campaign in 1968 — virtually unheard of at the time. During that same year, she appeared on the now-iconic cover of Ladies' Home Journal and, a year later, Life Magazine — a first for both publications.

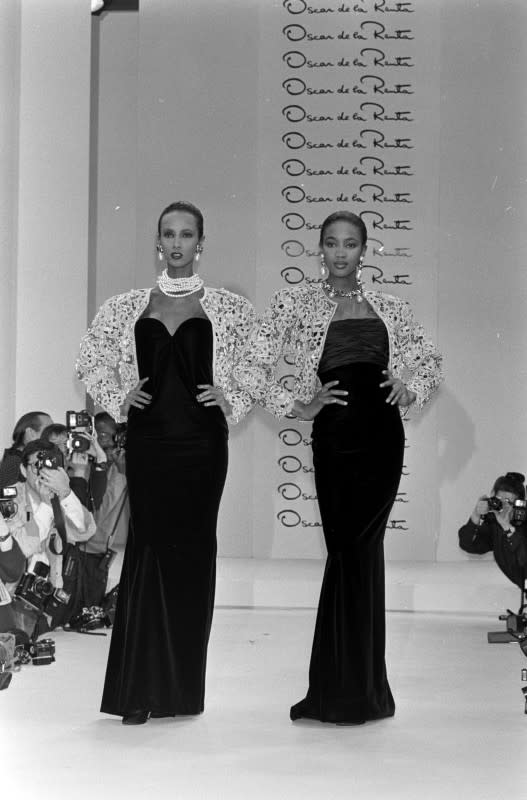

Other models made tremendous strides during the ensuing decade. Beverly Johnson was the first Black model on the cover of American Vogue and Cosmopolitan. Bethann Hardison was an early activist in model diversity while walking a number of top runways. The aforementioned Cleveland was a Halsonette.

Photo: Harry Benson/WWD/Penske Media via Getty Images

Towards the end of the 1970s, Black models were securing work on both sides of the pond, and they seemed to be finally getting the attention and acknowledgment they deserved. Then, the '80s happened.

The death of disco in 1979 closed out the high-flying boogie-woogie decade, and brought an end to the golden age of Black models, it seems. Sims retired, Luna passed away tragically at the age of 34 and Cleveland stepped away from the spotlight to raise children. In their place, a few prominent figures emerged, including Naomi Campbell, another favorite of Saint Laurent. Still, progress for Black models and designers seemed to slow. It felt like a complete 180° from the 1970s, marked by a return to full-blown conservative values backed by figures like Ronald Reagan and an empowered Republican Party. Taxes were down, defense spending was up and gains in Black arts were backsliding.

"Reagan put the distance from the '60s and '70s agendas of political activism and the Black middle class," Hughes theorizes, "and that's where you see the drop off; you didn't have the word 'diversity' in that narrative."

Photo: George Chinsee/WWD/Penske Media via Getty Images

Hughes notes that, while we may have seen fewer well-known Black models in the '80s, they were still out there, "There were still Black models working in Paris in the 1980s, on Karl Lagerfeld's runways and at the couture level," he says. Take Palmira "Pal" Henry, an Afro-Puerto Rican actor and model who worked exclusively for New York courturier Adolfo, a Saks Fifth Avenue favorite. Henry's appointment as Adolfo's in-house muse is that much more compelling when you consider that one of his most ardent and public customers, Nancy Reagan, was one of the main proponents of a return to conservative (read: white) values.

"Adolfo was at his height in that time period, and Pal Henry was this educated and sophisticated woman — and she was Black," Hughes recalls.

Through the '80s and into the 1990s and 2000s, we have had a sprinkle here and there of notable Black models who left their mark on the industry: Beverly Peele, Chanel Iman, Duckie Thot, Joan Smalls. But with the overall decline of the Supermodel concept, and with the biggest opportunities often going to those with famous last names and large social media followings, it seems unlikely that we'll ever see anything like the 1970s.

"I think models in general aren't popular anymore," Martin says. "Models used to be on covers; we saw them everywhere, but now that has changed tremendously."

Hughes agrees: "You can be the hottest thing for two seasons, and then it's kind of over. You're done."

In this digital age, we don't necessarily turn to the catwalk for the latest trends or the next household name. So maybe we'll never recapture the spirit or diversity of the 1970s — but we can still honor the legacy of the women who made the runway their own, even if just for that one moment in time.

Want more Fashionista? Sign up for our daily newsletter and get us directly in your inbox.