The ‘ravening wolf’ priest who led a doomed revolution

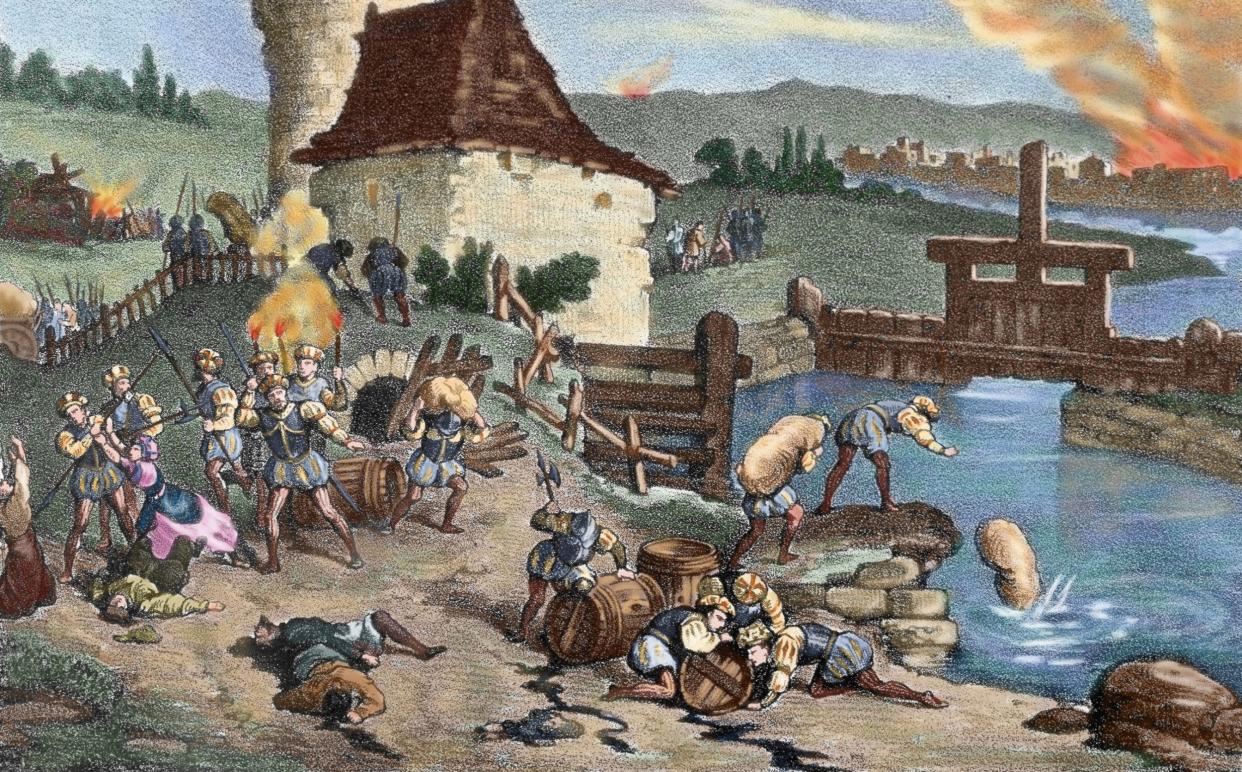

The decisive battle of the German Peasants’ War was fought on May 15 1525, upon a hilltop outside Frankenhausen, a small town in the central state of Thuringia. An army of around 8,000 peasants, gathered under rainbow banners, were demanding the overthrow of the existing social order. Their leader, the radical preacher Thomas Müntzer, pointed to the sky – where a rainbow-like halo seemed to have formed around the Sun – and reassured his troops that they should “fight with their heart and be of courage”. Within hours, the artillery-equipped army of the Saxon and Thuringian nobles had crushed the rebels’ flimsy fortifications and killed some 5,000 of them.

Andrew Drummond’s history steals its outstanding title, The Dreadful History and Judgement of God on Thomas Müntzer, from a pamphlet printed, soon after Müntzer’s execution, by his rival Martin Luther. The men were both important figures in the Protestant reformations that swept Europe at the start of the 16th century but, while Luther remained an ally of the aristocracy, Müntzer was a true revolutionary who demanded nothing less than the dissolution of feudal and religious structures and the full emancipation of the peasantry. As Drummond puts it, the latter approach was “playing with fire in an age of theological arson”.

It’s easy to understand why some were drawn to such lofty ambitions. Drummond begins by outlining the miserable state of your average Holy Roman peasant, and the apocalypticism that had taken root in Germany at the end of the 15th century. Müntzer too believed the world was ending, and that only the spiritually pure “Elect” were equipped to change the tide of history. There was a feeling – it may be familiar to those who remember the turn of 2000 – that some great but unknown change was on the horizon, accelerated by the emergence of a new form of communication technology: in their case, the Gutenberg printing press.

The echoes of the present day are not accidental. While Drummond conjures a sense of historical place – with credit due for capturing the religious lives of his subjects while largely dodging the dense mire of theology – The Dreadful History and Judgement… is very much a book in the New Left tradition of materialist history. We get a tightly narrativised case study of local conditions from which we can draw easy parallels to modern social movements, but we sometimes lose sight of history’s specific power-centres. The figure of the “early capitalist”, for instance, receives more frequent mention than Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor.

Printing allowed for the spread of ideas by prominent intellectuals, but it also became a vehicle for some impressive mudslinging. In the various tracts that emerged, Müntzer was branded a “ravening wolf” and a “false prophet”, while a fellow firebrand, Heinrich Pfeiffer, was said to want “to introduce murder, riot, overthrowing of authority”. Müntzer’s ripostes laid into the “lavish mimicry of the Godless” and painted the nobility as a “dribbling sack”. Luther, he claimed, couldn’t have drawn crowds as big as his “if he were to burst”.

When he wasn’t writing, Müntzer’s career took him from town to town, preaching and agitating. His first real controversy arose in Zwickau in 1520, where he, along with a weaver named Nicholas Storch, incited a series of riots against the local Catholic clergy. He was firmly told that he had to leave. In Prague in 1521, things continued in much the same way, and he fled under a hail of stones. He was run out of several other towns, climbing over the walls of Allstedt in August 1524 after a warning from local leaders, and slipping out of Mühlhausen a month later after the townsfolk voted to get rid of him. In both of the latter cases, Müntzer left his wife Ottilie and his young child behind.

And that’s the thing. Even accounting, as Drummond does, for the fact that the historical record was largely written by Müntzer’s enemies, Müntzer at no point comes across as a pleasant man, much less one who lives up to the ideals he ignites in the peasants whom he’ll eventually send to their deaths. The reformist Philipp Melanchthon, whose second-hand account no doubt reflects plenty of Lutheran bias, presented him as a charlatan who told the peasants that he would “catch all the bullets in his sleeves”.

After the massacre, Müntzer somehow escaped the hill and was captured at a nearby inn; he would be executed soon after, but not before sending a final letter to his remaining acolytes. Here he claimed, in the tone of all failed revolutionaries, that his enterprise collapsed because it didn’t go far enough – that those who had died “only considered their own profit and thus destroyed God’s truth”.

Drummond has written a blisteringly good book about personal enmity, and the difference between revolution and reform. Müntzer’s head ended up on a spike outside of the gates of Mühlhausen, but Luther changed Christendom forever. The Frankenhausen hilltop was flattened in the 1970s by the East German government. They built a museum there, with a panoramic mural dedicated to the more-than-100,000 peasants killed in the war. Under the rainbow, defiant to the last, stands Thomas Müntzer.

The Dreadful History and Judgement of God on Thomas Müntzer is published by Verso at £25. To order your copy for £19.99, call 0844 871 1514 or visit Telegraph Books