Protests and pétanque: The wonderfully French row brewing in Paris

A wonderfully French row is underway in the leafy Parisian district of Montmartre, once famed for its bohemian artists but lately increasingly gentrified and commercialised by mass tourism. It involves angry protests, accusations of harassment, a bitter row between former friends, a luxury hotel – and pétanque.

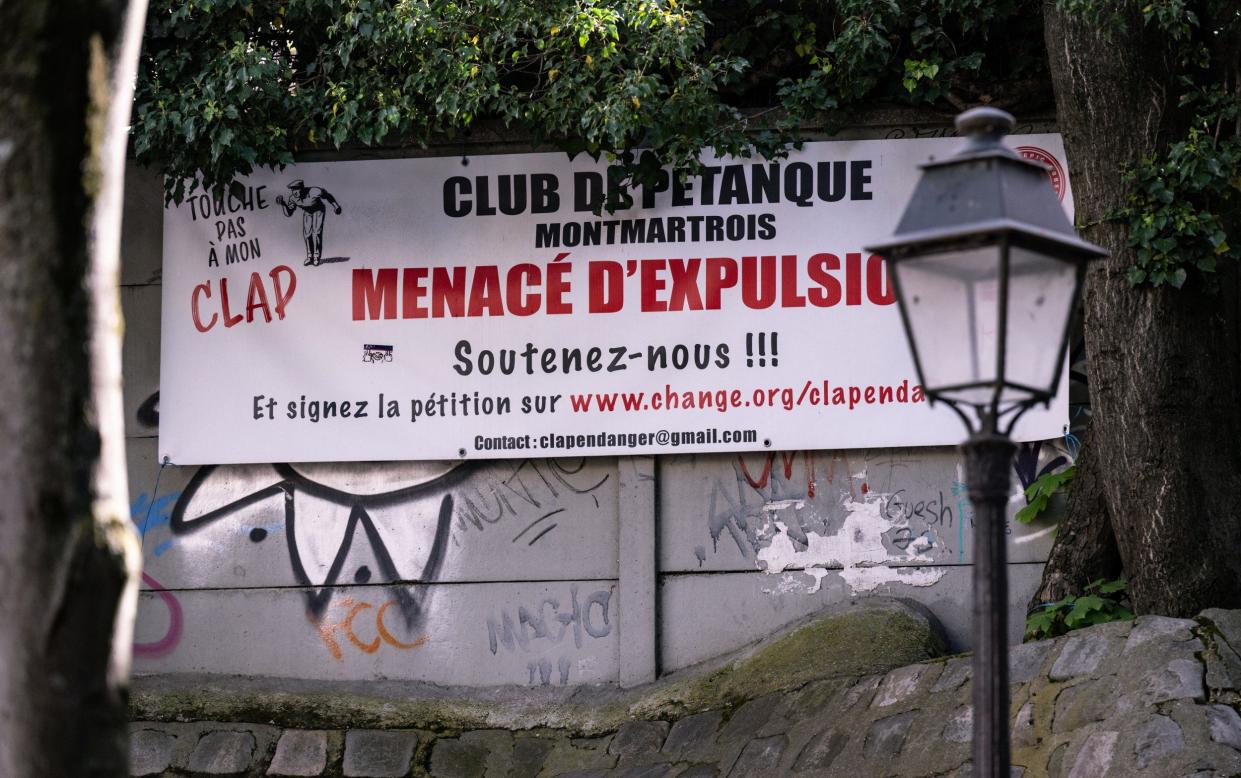

The 52-year-old pétanque club, Club Lepic Abbesses Pétanque (Clap) has been given court orders to leave its picturesque home in one of the most attractive and high-end areas of Montmartre, close to the Sacré-Coeur Basilica. After a years-long battle with Paris City Hall, members have now resorted to pitching tents on the site, keeping a 24-hour vigil to prevent the area being cleared. Every day they stay they incur another €500 (£430) fine.

The land, which contains eight pétanque pitches and a café kiosk, originally belonged to an artist of the Barbizon School called Félix Ziem, whose daughter sold it to Parisian authorities. In the 19th century, this area was known as the Maquis de Montmartre, an unofficial cluster of wooden huts where poor Parisians lived. But as Montmartre became a fashionable venue for counterculture and cabarets during the Belle Époque, many inhabitants of the slum were moved out. In the early 20th century, Avenue Junot was built, lined with imposing buildings that today contain some of the most expensive and sought-after apartments in Paris. Tucked just behind them, out of the view of tourists and even many locals, Clap’s metal boules have been clacking away since the Seventies.

“This club was created 52 years ago, but [...] we have not been here illegally for 52 years, contrary to what people say. We can prove that,” said Luc Magnin, a member of Clap, on Tuesday morning. Indeed, the town hall of the 18th arrondissement, where Montmartre is located, corroborates that the club was established with the consent of the local authority.

Clap’s residence almost ended in the 1980s, after plans were unveiled to build an underground car park on the site, but this was ultimately blocked after years of protest. In 1991, the surrounding area was surveyed and classified as protected, and then in 2022 City Hall called for proposals to officially lease the land.

Jean-Philippe Daviaud, a Paris councillor in charge of commerce, artisans and Europe for the 18th arrondissement, said: “At a time when this area was very working class, this land was made available to a local boules club. It has changed a lot since then, but [the arrangement] stayed like that – in a very informal way. Today, situations like that don’t exist anymore. The city does not have the right to give [away] a piece of public land [without] a contract, and payments from the organisation in question in exchange for occupying the space.”

Representatives of Clap insisted that it made efforts to create an official contract, and begin paying rent, but claimed they were dismissed or not looked at properly. It added that it only had two months to put together a proposal, which had to adhere to strict criteria for the land to be open to the public, ecologically beneficial and economically viable.

The contract was ultimately awarded to Oscar Comtet, director of the Hôtel Particulier Montmartre, a neighbouring five-star hotel. He plans to open the space to the public, replacing the food kiosk with a pond, and some of the pétanque pitches with a garden (though six will be kept, including two suitable for competitive play). The planned garden, which already has a website and Instagram page, will be called Jardin Junot, and feature a petting zoo for children, beehives, cultural events and family-friendly activities.

But there’s a novel-worthy twist. Comtet is a local – and a member of Clap since the age of 12. “We saw Oscar grow up,” said Clap spokesman Maxime Liogier. “We taught him to play boules, and he was good. He had talent.”

A tired-sounding Comtet responded: “Me, I have nothing to say except I am sad that it doesn’t suit them. I am fighting for this land to be reopened to the public, unfortunately it was made private [by Clap]. It’s a piece of public land, the town hall can’t access its own land, so I don’t know what to say. It’s really a shame.”

The Clap protestors accuse the project of “green washing” and think the plans are a mere pretext for expanding the hotel, an accusation roundly denied by Comtet and city authorities. The club frames it as a David versus Goliath battle: ordinary folk against a luxury hotel that can afford to invest hundreds of thousands into the land, advertising its project with a peppy social media presence.

The hotel director said that the proposed garden “is absolutely not linked to the hotel. It’s financed by the hotel, but it’s open to the public”. He insisted “it’s not a project for tourists, it’s a project for the people of Montmartre.”

In addition, Daviaud of the 18th arrondissement council maintained that the sports club was ultimately unwilling to give up the elements of the club that make it incompatible with Paris in the 21st century: namely the hosting of a private club on public land, and the serving and consumption of alcohol and other refreshments in the kiosk without the necessary permits.

Both Comtet and the town hall also said that the hotel director, his family and his staff have been threatened and harassed by protestors, reportedly leading to resignations from some of the people working there.

Beyond the mud-slinging and legal wranglings, Clap’s campaign seems to give voice to a more generalised feeling in Paris: a fear that the idiosyncratic charm of the city is being scooped out and sold. Earlier this year, graffiti was spotted on the sleepy square in the Latin Quarter where Netflix series Emily in Paris is filmed reading “Emily not welcome” – a response to some locals feeling inundated by tourists.

This dispute also comes against a backdrop of the approaching Olympic Games, the subject of criticism from some Parisians who feel the event plans prioritise the perception of the country internationally over the needs and concerns of locals.

Montmartre is concurrently in the process of applying for Unesco World Heritage status. Liogier lamented: “They speak about listing Montmartre with Unesco, but listing what? The tourist coaches? We are one of the last corners of neighbourhood life in Montmartre.

“It’s the death of… the soul of Montmartre, where Montmartrois can still meet, exchange, play cards and boules. Montmartre became known the world over because it was a real place, a working-class place.”

He added: “We’re not thugs. Far from it – but what happened is against the moral order, that’s why we are rebelling: we can’t agree to accept the absurd.” When I suggested the saga is a microcosm of every French stereotype – boules, rebellion, luxury hospitality – he couldn’t help but smile: “It’s French stuff, I know, I know, I know!”