Poem of the week: Prodigal Son by Gabriele Tinti

Prodigal Son

I will meet you in the morning,

in front of the museum, where

you never thought to take me.

I will recognise you in an ancient

stone face, and I will want

to hold you close

in the embrace that you and I,

after all, never had.

And together we will lower our gaze

so as not to see in the eyes the horror

of time passed too quickly,

to finally think of something else.

Translated by David Graham

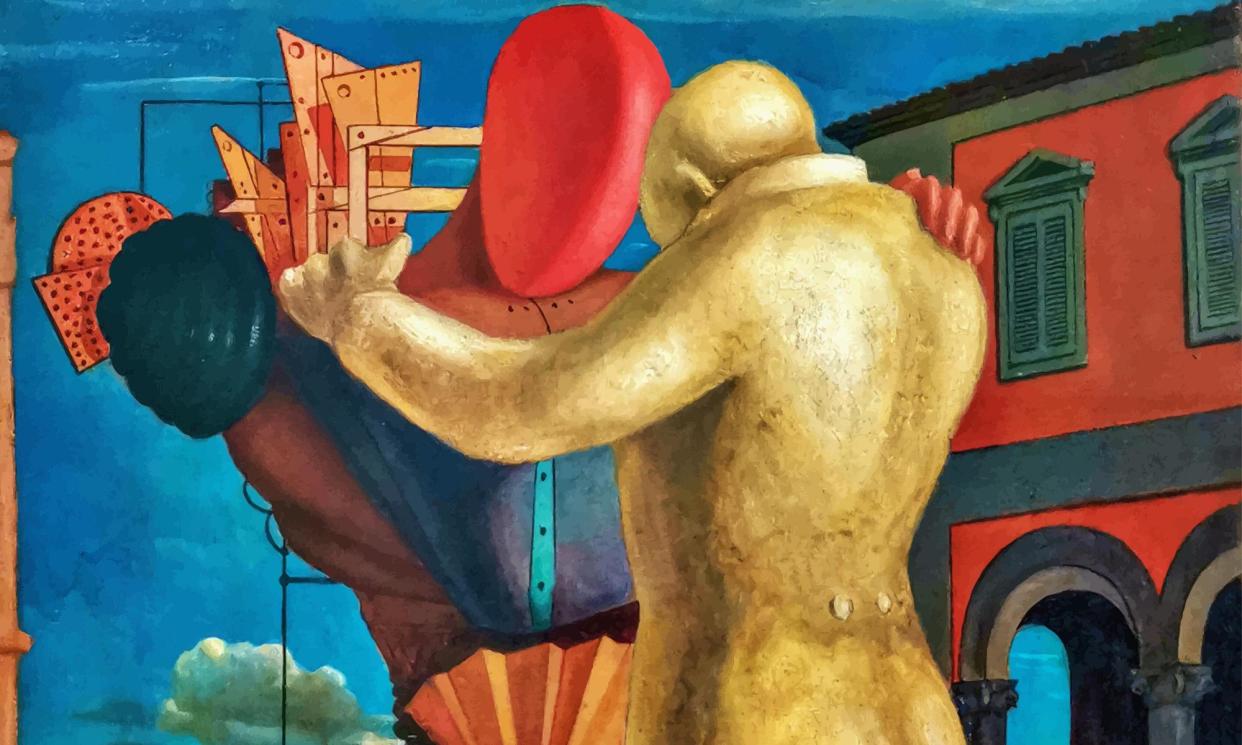

Prodigal Son by the Italian poet and translator, Gabriele Tinti, is from a group of poems inspired by paintings by the Italian surrealist Giorgio de Chirico, including Gladiators, The Seer and Song of Love. From his recent collection Bleedings: Incipit Tragoedia, the group interestingly complements Tinti’s re-conceptions of ancient epigrams and funerary inscriptions.

In de Chirico’s 1922 painting The Prodigal Son the statue-father has stepped down from his pedestal outside what is often identified as the Archaeological Museum of Naples. The son confronts him with wary flamboyance. He has been constructed, or has constructed himself, from various materials, an extravagantly “self-made man” whose colourfully reprobate past must be unimaginable to the grey, formal, age-shrunken father. The two figures look, literally, ill-suited. Neither’s face is visible, and some commentators have discerned refusal of contact in their embrace. Tinti’s poem, without backing away from the suffering that is the major theme of his collection, delicately suggests otherwise.

Tinti approaches the ekphrastic challenge from an angle that enables him not merely to heighten the painted image but to show us something entirely new about it. All four of the poem’s tercets are spoken by the son, and introduce a protagonist more thoughtful, pained and recognisably contemporary than the figure in the biblical parable.

“I will meet you in the morning,” the son begins, addressing his father the night before the encounter de Chirico depicts. The chronology opens a space between the poem’s vision of the embrace and that of the painting. It provides context. It tells us that de Chirico’s stylised figures have a private human relationship inaccessible to public display.

The figures in the painting are time-trapped. But the son in the poem is planning to cross time to meet his now faltering and uncertain father. When he says “I will recognise you in an ancient / stone face” the line break, and the indefinite article, suggest a barrier and perhaps a gasp of disbelief or sorrow. The stoniness of the face is primarily that of its material, the coldness and hardness inherent. It won’t militate against intimacy, or obscure the son’s recognition. In the lineation of “I will want / to hold you close” the reader might hear hesitation, a trace of resistance, but no threat.

The father’s shortcomings in his relationship with his child are made clear. Their proposed meeting place is “the museum, where / you never thought to take me”. The embrace will be one “that you and I, / after all, never had.” These statements, though made in a tone that seems matter-of-fact, must bear a trace of accusation. But the meeting will happen, there’s no doubt about the son’s steadily focused intention. His words imply tentative forgiveness of the negligent father. The figures from the original parable seem to have changed places.

Their connection will be imperfect. The son knows the reason, and puts it strongly: “together we will lower our gaze // so as not to see in the eyes the horror / of time finally passed too quickly”. This predicts the highest point of communion between the two figures. Many possibilities of reconciliation have vanished. Both are changed. The truest connection between them is the shared “horror” at what is now irretrievable. It’s ultimately the horror of death. But a restorative gentleness appears in the son’s suggestion “to finally think of something else”.

Perhaps the withdrawal of each man’s gaze also represents a freeing from time. The plan completed, the poem ends at the exactly right moment, and returns us to the painting. Each figure is thinking of “something else”. However, the poem has suggested it’s a “something else” that belongs to what the son and father know of each other, a memory, or perhaps a fragment of future hope.

David Graham is a professional Italian-English translator living in Venice. He mainly translates catalogues for art exhibitions and museums, but also enjoys grappling with poetry. He grew up in New Zealand and moved to Europe in 1982.

Bleedings: Incipit Tragoedia is reviewed here. The original Italian for this week’s poem appears below:

Figliol prodigo

T’incontrerò la mattina,

davanti al Museo, lì dove

non mi hai mai saputo portare.

Ti riconoscerò in un volto

antico, di pietra, e mi verrà

la voglia ti stringerti forte

in quell’abbraccio che io e te,

in fondo, non ci siamo mai dati.

E insieme abbasseremo lo sguardo

per non vedere negli occhi l’orrore

del tempo passato troppo in fretta,

per pensare finalmente ad altro.