A new planet in the desert: why did the $200m 'Spaceship Earth' experiment end in disaster?

In the morning of September 23 1993, at a giant glass structure in the Arizona desert, journalists from around the world were gathered to stare at a door. Exactly two years earlier, that door had been sealed. Now it swung open again, and for the first time since their self-imposed exile, eight people in red overalls stepped back into America.

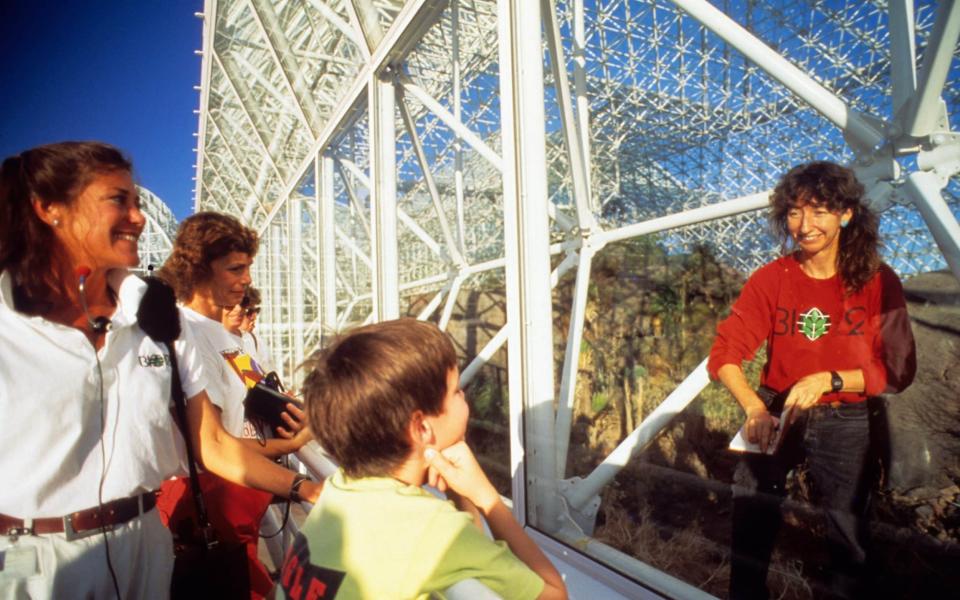

Biosphere 2 was a geodesic dome, eight storeys high, 91ft tall, occupying 3.14 acres. It had cost $200 million (£125 million), and housed more than 2,300 plant and animal species, as well as a human crew of eight “Biospherians”.

It was, and remains, the largest closed system ever built. The intention was to create a self-sufficient world. Its atmosphere would self-replenish; its inhabitants would grow their own food. The habitat was designed with a mangrove swamp, a savannah and a living coral reef. An entire planet, under glass.

The drama of Biosphere 2, from its beginnings on a commune in rural New Mexico to its acrimonious and messy end, is the subject of Spaceship Earth, a new documentary film by the director Matt Wolf. (The film is named after Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth, a 1969 book by Buckminster Fuller, inventor of the geodesic dome.) When Wolf first saw the photographs of the Biospherians’ dazed exit in 1993, he tells me over the phone from New York, “I genuinely thought they were stills from a science fiction film.”

It all began in San Francisco, in the 1960s, with John Allen. This curious man attracted a group of supporters by founding an avant-garde theatre group – The Theatre of All Possibilities – then decamping to a ranch in the scrub, which the new commune named “Synergia”. They hooked a venture capitalist, Ed Bass, who stumped up the cash for their moneymaking schemes: a self-built ship called the Heraclitus, a hotel in Kathmandu.

Allen was obsessed with the idea of humanity surviving catastrophes, from famine to nuclear war. Space was the natural next frontier. Biosphere 2 drew on a Russian analogue, Bios-3 in Siberia, an early Seventies closed ecosystem designed to model future space missions. Kathelin Gray, a Synergian who became a co-director of Biosphere 2, said: “We loved the idea that when you’re thinking of colonies in space, you’re thinking of sustainable living on Earth.”

The Biospherians look back on their home with surprising fondness. One, Linda Leigh, compares it to “Eden”. The team saw the project, Wolf explains, as an “almost Biblical experiment, a sort of Noah’s Ark”. And it was the gentlest of dreams: they were stewards, not survivors-to-be. Unlike Noah, they kept predators out; no animal posed any threat to them. There were chickens, goats and pigs, for milk and occasional meat. (They were mostly vegetarian, out of practicality; to raise meat, you need more land.)

But Edens can only ever be lost, and so it was here. Most of the animals died; by the second year the pollinating insects had been supplanted by swarming pests. Worse, microbes were flourishing in the soil, altering the atmosphere. The humans couldn’t fix it. Carbon dioxide had to be manually “scrubbed” from the air, and after 16 months, emergency oxygen was piped in, too. As Wolf puts it, Biosphere 2 was “plagued by its own ecological drama that was spiralling out of control”.

The human inhabitants didn’t help. Ray Waldron, who was the only doctor on the crew, believed that with the right diet, people could live for 120 years. The project’s managers endorsed his shtick; before long, the Biospherians were wasting away. Leigh told Wolf that they spent months “suffocating and starving”, while Sally Silverstone drily recalls their diet: “Beetroot soup and beetroot salad, with a side of beetroot.” It took months of this before the weight-loss stopped.

Tourists flocked to gape through the glass. The vox-pops in Spaceship Earth show an older Christian woman who doubts the project would work – “people are too abusive” – and a group of teens who seem no more convinced. (“I wanna know what a black girl from Brooklyn would do in a biosphere!”)

The crew held video-conferences, recorded messages and sent emails to the watching world. Most of them had cameras, to make diaries of their lives; added to the official footage, this created an archive of extraordinary depth. Silverstone practised the flute; Jane Poynter liked to paint; all seven became expert in “Biospherian cuisine”. But the tabloids wanted news from the bedrooms, and their prurience irritated the crew. As one, Mark Nelson, put it: “People are people. Everything you might expect to happen with people has happened in here.”

In truth, it was less Love Island, more staid house-share. “Two couples went in,” Wolf points out. “My sense is that it was fairly tame, because half of them were already coupled up.” There was, he says, “plenty of private space” in the habitat. “The Biospherians could go scuba diving in their miniature ocean when they needed to get away, or they could climb up the trellis and hang out in a tree.”

But divisions grew. The project was hamstrung by allegations of “cheating” – in particular, those CO2 scrubbers – and the press became hostile. The Biospherians began to quarrel with the project’s directors. By the second year, some of the crew wouldn’t speak to the others, except on the topic of work. In his 2018 book, Pushing Our Limits, Nelson remembers “a Sunday night dinner where we enjoyed a precious bottle of home-brewed banana wine”. One Biospherian tried to raise a toast: “To the traitors!”

In 1994, a second attempt at crewing the Biosphere collapsed. The poison, by now, was rife. The backer Ed Bass took out an injunction against Allen and his team. A young tyro from Goldman Sachs, by the name of Steve Bannon, was put in temporary charge. He appears near the end of Spaceship Earth, looking young, but just as menacing. Wolf’s interviewees are unanimous on how malignant he was. (A leaked recording, played in Wolf’s film, shows Bannon’s pride at ousting Allen: “I kicked his ass.”)

In the film, Bannon becomes a metaphor for the triumph of corporate logic over starry ideals. “I mean, Bannon was instrumental in the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the Paris accords,” says Wolf. (He didn’t approach Bannon himself: “I feel he has enough platforms to speak.”) The Biosphere 2 story ends well: Columbia University took over the site, ended the closed-system concept and funded less showy research, which (now under the auspices of the University of Arizona) continues there today.

Wolf, however, is disappointed. “So much intention and thought went into making this a closed system that would sustain itself for 100 years.” Allen, who expected there to be several false starts, blames the media for Biosphere 2’s premature end. “People did not understand the point,” he says. “Biosphere 2 brings you a visceral sense of how fragile everything is.”

On that score, all failure would be a form of success. (Corporations call these “learnings”, and hope to emerge unstained.) Biosphere 2 was so named because it modelled Biosphere 1 – the Earth. “People invent a new world”, Wolf says, “and they inherit all the problems of the original.”

Spaceship Earth is available on demand from July 10