Pie crusts and pearls: the unexpected return of the Sloane Ranger

There is a scene in episode three of the current series of The Crown, when a young Diana Spencer returns to her shared flat in Earl’s Court, west London, with the news that she is engaged to Prince Charles. Enveloped in shrieks and hugs by her flatmates, there is more to this moment than celebration. The four young women – in their sensible knitwear, pie-crust collars, calf-length skirts, silk scarves and tank tops – showcase the Sloane Ranger style. After her engagement was announced in 1981, Diana was photographed by the press, and the look went from SW5 to nationwide.

The cultural commentator Peter York is in a unique position to discuss all things Sloane. In 1982, he co-wrote (with Ann Barr) The Official Sloane Ranger Handbook. A huge hit, it put a magnifying glass over a lifestyle lived by young posh people like Diana and her friends. The book reports on – and mocks gently – every aspect of their lives, from a reluctance to use postcodes (“Country Sloanes hate to admit they live on a road. As a result, some letters never reach them”) to their penchant for referring to balls – as in the events – as “bollocks”. Although he has not watched The Crown – “Most Netflix content is from the freezer, [it’s] long shelf-life content” – York describes the latest series as “my era”. He also has a cut-glass accent that would fit right in.

With some help, York invented the term “Sloane Ranger” in 1975, when he wrote, also with Barr, an article for Harpers & Queen about the demographic congregating around Sloane Square in Chelsea. “We were going to call it the Connaught Rangers, thinking about the places where those girls would work: St James’s and Mayfair,” he says. “[But] one of the subeditors, Tina Margetts, came up with this brilliant pun on the Lone Ranger. The moment she said it everyone knew it was the answer.”

York’s book has Diana – as she then was – on its front cover, and calls her the “supersloane”. Was she a typical Sloane Ranger? “Yes, but no,” he says. “She wasn’t a nice upper-middle-class girl. She was an absolute, oak-tall aristocrat. When the first Earl [of Spencer] got married, the diamonds on his shoes were worth – in contemporary money – £3m.”

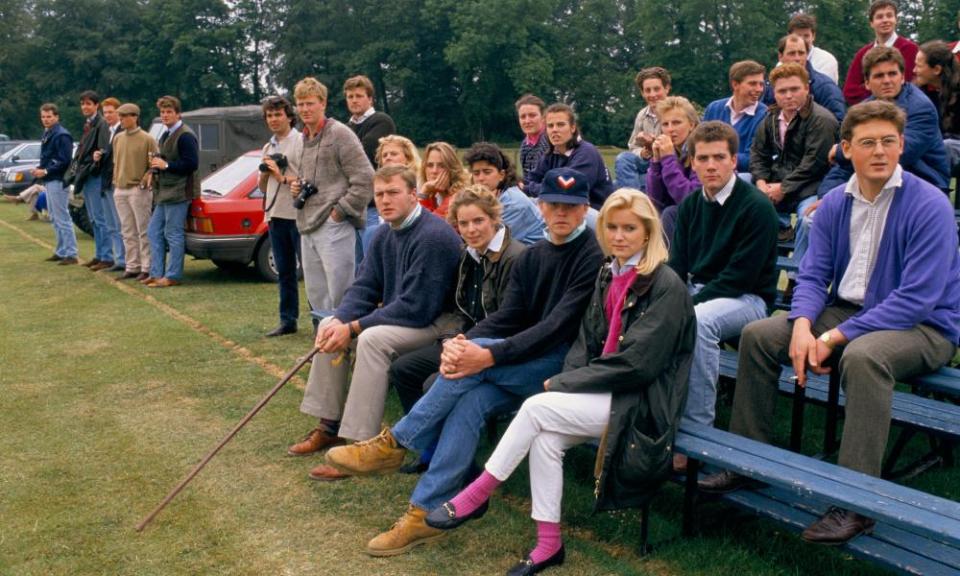

Nevertheless, Diana lived the Sloane Ranger lifestyle and “wore what her contemporaries wore”, as The Crown shows. As she became more famous, the look spread. “We’re talking of a time before the internet, before Pinterest and Instagram, before any of that,” recalls York. “So the fact is that Sloane Rangers did live in a bubble, and it was an aesthetic bubble as well.”

He says that people from outside certain regions would not have seen this style before. “When you start to see it in national newspapers and on the telly, you think think: ‘Gosh’,” he says. “Whereas, if you lived in Earl’s Court or certain bits of Gloucestershire, you would think that’s the way people dressed.”

Seen as the style of the wealthy, it was understandable that the hoi polloi should want in. The Sloane Ranger went from a lifestyle to “a look”, a shift that York calls “cultural appropriation”. Given contemporary debates about the phrase, this feels questionable given that rather than an oppressed culture being appropriated, this time it was a privileged group.

But strangely, perhaps, Sloane Rangers, with their Barbours and ballet pumps, are still a part of the British cast of characters nearly 40 years after York’s book was published. So, are there new Sloanes? “Yes, but it’s changed,” says York. For one thing: “Most Sloanes have been priced out of places around Sloane Square and they live in places like Clapham.”

While these Clapham Sloanes might be more likely to be found in – say – expensive loungewear, the original look seems likely to go mass again, with The Crown faithfully reproducing it, and Diana a style icon of 2020. A new generation is already taking to the silk scarf in hair and around necks, velvet headbands as well as pearls and pie crusts. While this could be read as yet another revival of a youth culture moment, there is a crucial difference, says York. Since the Sloane hails from the ruling class, it is about the status quo rather than rebellion.

“With, say, skinheads and mods, even though you can place them socially, they are elective,” he says. “‘I’m putting these clothes on consciously, to make a statement, and belong.’ With the Sloane Ranger stuff, you weren’t making a statement … it evolved from a particular kind of parent and their dress code, and a particular kind of schooling and that dress code. All those things are mixed up there.”