Paris according to the world’s first celebrity, who dodged the nunnery for a life of debauchery

One evening in 1859, a 15-year-old convent girl arrived at the Comédie-Française, Paris’ great classical theatre, with a party of adults. There was her mother and her aunt, both high-class Parisian courtesans, and the Duke of Morny, a regular at her mother’s salon. In a private box, the group joined Alexandre Dumas, author of the Count of Monte Cristo, probably another of her mother’s clients. As the lights dimmed and the curtain rose, the young girl was on the edge of her seat. “I thought I was going to faint,” Sarah Bernhardt would recall a half century later. “It was as if the curtain of my future life was being raised.” In that moment, she decided she didn’t want to be a nun after all.

Over a career spanning six decades, Sarah became the most famous actress of her age, bestriding Parisian cultural life and the theatrical world across four continents. Known as La Divina, she virtually created the idea of celebrity with the kind of fame that became so much a part of the modern world decades later with the advent of Hollywood.

This year, 100 years after her death, Sarah is back, taking centre stage once again in Paris, at the Petit Palais, with an extraordinary exhibition. It tells the story of her remarkable life from her origins in the mid 19th-century demi-monde to her celebrity status by the beginning of the 20th century.

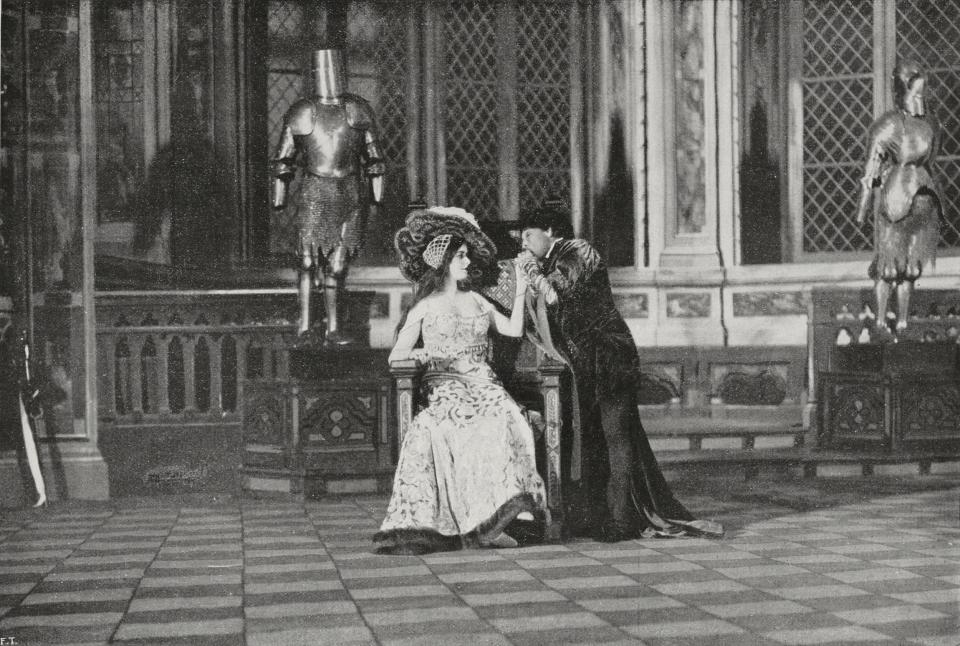

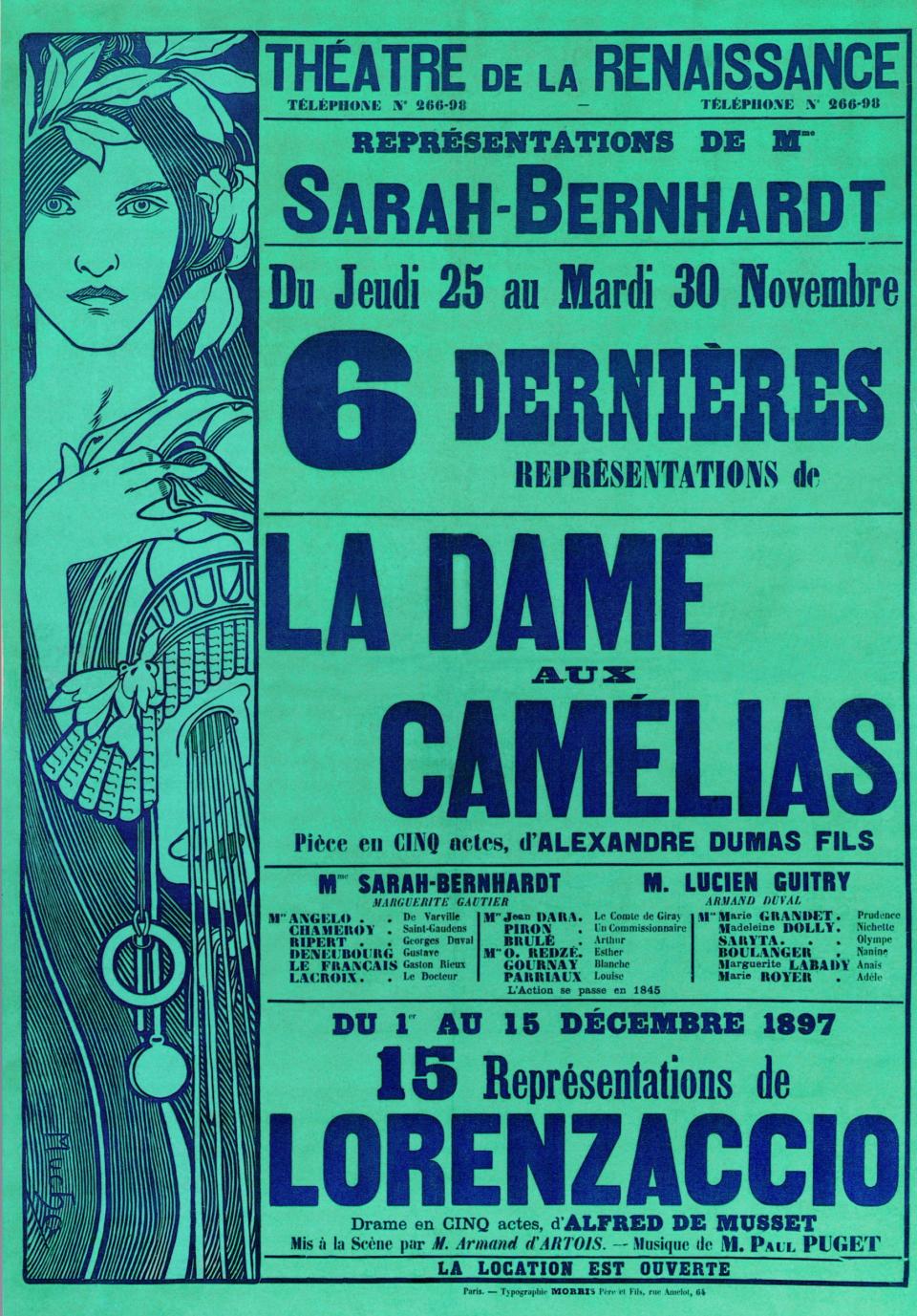

There are famous paintings and photographs, audio and film clips, posters and souvenirs, charting a life of her own invention. We see Sarah in her great roles – Aida, Cleopatra, La Dame aux Camelias, Theodora, Marie Antoinette, Elizabeth I, Tosca and, at the age of 45, the 19-year-old Joan of Arc. She also famously played male parts, including Hamlet in a production that came to London.

By 1900, at the time of the Universal Exhibition, when the Petit Palais was built, her fame had reached such a pitch that shops began to do a roaring trade in Bernhardt souvenirs like postcards, fans and perfumes, while advertisers for everything from biscuits to rice powder queued for her endorsement.

In the First World War, she entertained the troops in spite of the fact she had had her right leg recently amputated from an injury in Rio de Janeiro when a hapless stage-hand had positioned the mattress incorrectly for Tosca’s famous leap from the ramparts.

But the exhibition also holds a mirror to the Paris of the Belle Epoque, that ‘enchanted interlude’ between the Commune of 1871 and the catastrophe of the Great War, a golden age of glamour and decadence, of theatres and fashionable restaurants, of high society and a great flowering of arts.

To this day, the Belle Epoque echoes across the city. You find it in the architecture of the Right Bank, in the bistros of the Left Bank, along the grand Hausmann avenues, in decoration details like those beautiful cast iron Wallace fountains and the iconic Morris columns with their advertising hoardings, in the Art Nouveau stylings of the metro, and in the Parisian sense that sophisticated culture rarely extends beyond its own périphérique.

The Belle Epoque is the Paris we still visit. Bernhardt was not just one of its leading figures. She was its incarnation, flamboyant, liberated, romantic, supremely confident, and more than a little outlandish.

Eager for some romance myself, I emerged from the exhibition to hurry across town to Bofinger, where I had a hot date.

Opened in 1868, and now recognised as an historical monument, Bofinger is fantastic confection of colossal mirrors and polished wood, brass rails and frosted globe lamps and dark red banquettes, all beneath a stunning dome of stained glass, like a coloured embrace of the Belle Epoque.

The menu is drawn straight from that timeless Parisian brasserie hymnal – oysters on vast platters of ice, onion soup, foie gras, Alastian choucroute. White aproned waiters who appear to have been here since Sarah’s day bustle back forth. Of course this is Paris, so the waiters are sniffy and difficult. “They were probably sniffy to Toulouse-Lautrec in his time,” my date said. “If he could cope, so can we.”

Sarah’s seemed to be a lifetime of hot dates. Known as the ‘panther of love’ in the Latin Quarter, her amorous adventures were legion. There were elegant young hussars, various viscounts, bankers and marquises and military officers, painters and writers, an Egyptian diplomat and the Prince de Ligne, probably the father of her son Maurice, whose aristocratic family stood in the way of her marriage.

There was Edward, Prince of Wales and Napoleon III, and almost all of her leading men. There was Charles Haas, the model for Charles Swann in Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past; Bernhardt herself was Proust’s model for Berma. There was Louise Abbéma, a prominent member of Paris’ lesbian community, Victor Hugo, 42 years her senior, and Lou Tellegen, 37 years her junior, whom Sarah described as “un bel animal… a lion”. I can see that life as a nun wouldn’t really have suited her.

Many of these were undoubtedly convenient rather than romantic liaisons. Bernhardt had begun in the Parisian demi-monde inhabited by her mother in which wealthy gentlemen frequented the salons of high-class courtesans. In a 19th-century leather-bound police register in the exhibition, a record of the activities of Parisian courtesans, we find Sarah herself, on page 158. Still a teenager, she is listed as being popular with “old men and members of parliament”.

But in the same room an audio reading of her letters to the dashing and priapic Mounet Sully attests to the kind of genuine love affair that was so much part of her emotional life. It is all “painfully beating hearts” and “eyes stinging with tears”. “When you no longer love me,” she wrote breathlessly, “the grave is so close”. In later life, when asked when she would give up love, she replied, “with my dying breath”.

In search of the divine Sarah, I began at the end, in the Pere Lachaise cemetery. On her death in 1923, it was said that half a million people lined the route of her cortege and extra carriages had to be hired to transport the enormous wreaths. In the cemetery, I climbed melancholy cobbled paths, between broken headstones and barely discernible inscriptions. Père Lachaise is a who’s who of Parisian death, with the great and the good cheek by jowl, or at any rate, skull by jawbone.

Everyone is here – Zola, Proust, Delacroix, Chopin, Pissarro, Colette, Heloise and Abelard, Oscar Wilde, Edith Piaf, and dozens of other familiar names. It was like one of those fantasy dinner parties where you imagine inviting figures of the past, a collection of fascinating names, to gather in a single place.

Surrounded by the graves of so many of her friends and lovers, I found her stone mausoleum, high up among a clutter of trees and old leaves, adorned with just her name. A century has reduced the hundreds of wreathes to a single dry rose left by an anonymous admirer.

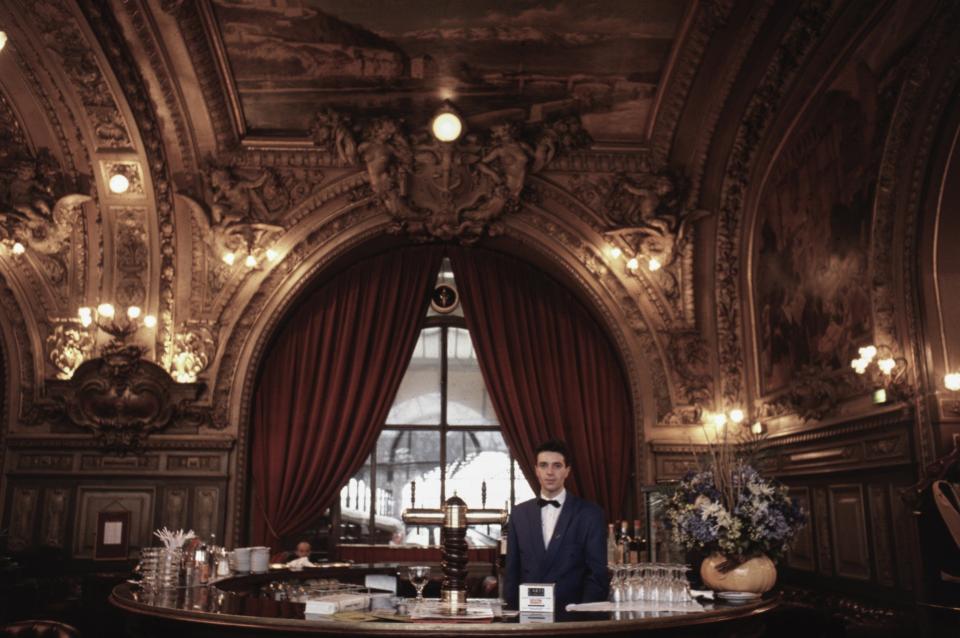

Setting off on the trail of her life, careening from one Belle Epoque fantasy to another, I dined beneath the gilded ceilings and the outsize chandeliers of Le Train Bleu at Gare de Lyon, and had coffee and croissant on the terrace of the fabulous Café de la Paix, where the barman claimed his great-grandfather had served Proust. In the Musée d’Orsay, I went to see the cabaret dancers and the street scenes of the period in paintings by Manet, Pissarro, Toulouse-Lautrec and Degas.

In the Musée Carnavalet, dedicated to the history of Paris, I hurried past Marie Antoinette’s prison cell, past Napoleon’s picnic set with its gold cutlery and gold handled toothbrush, to the grand rooms of the Belle Epoque. There was a sense of dramatic change in the era, and part of its freedoms were the faltering beginnings of female emancipation.

Paintings of the Seligmann collection depict a new generation of women, of which Sarah was a leading figure – confident, vibrant, more independent with stiff black-suited gentlemen circling in their orbit like moths. Already the shift in female fashion is evident, away from the structured corseted garments of an earlier generation to more flowing freer lines.

Wayward and impulsive, Sarah found, like so many of the celebrities that came after her, that well-publicised eccentricity served to promote her fame. She slept in a velvet lined coffin, wore a hat adorned with bats and kept a large menagerie of animals including turtles, a parrot, a monkey, a wolfhound, several chameleons, and a cheetah which she purchased from an animal dealer in Liverpool. In New Orleans she added an alligator to her household though he soon succumbed to a diet of milk and champagne.

Always a prima donna, she travelled in a private train while touring North America with two maids, two cooks, a waiter, a maitre d’, and her personal assistant, as well as her own ‘palace’ carriage. Always insisting on being paid in cash, she returned home from America with a chest filled with almost $200,000 in gold coins, the equivalent of several million today.

Though difficult to assess now, her style seems to have tended towards the histrionic and the eye-rolling melodramatic. George Bernard Shaw condemned her acting as egotistical. There was the sense that she was always just playing Sarah Bernhardt. It was a manner suited to her era though perhaps by the end of her life already falling out of fashion, superseded by a restrained naturalist manner of actresses like Eleonora Duse. When her funeral cortege passed along streets lined with mourners in March of 1923, the rumble of the carriage wheels on the cobblestones was not just the death knell for Sarah. It also sounded the end of an era as a more prosaic modern world was closing in on Paris.

Stay

Le Bristol

Impossibly grand, with a secluded courtyard garden restaurant, ateliers making their own pastries and chocolate, a pool styled like a 1920s cruise ship, a three-Michelin-star restaurant and a resident cat called Socrates. Check out the oval wood panelled ballroom where Josephine Baker celebrated her 50th anniversary as an entertainer. Doubles from €1,500.

The Maison Souquet

It has recreated the atmosphere of the Belle Epoque maison close, or bordello, that it once was: reams of lush velvet, polished mahogany, tasselled lampshades, and handsome chaps in black tie. You half-expect Toulouse-Lautrec to appear, paint box in hand, from behind the red curtains. Doubles from £500.

Castille

Located on one of the smartest streets of the Right Bank, next door to Chanel; Coco began by providing hats for the mistresses of the demi-monde in 1909. In the cosy lobby it is easy to imagine Sarah arriving with her entourage and cheetah on her way to an assignation in one of the sumptuous suites. Doubles from £356.

Eat

Bofinger

The flagship of the Flo group of brasseries, dining in Bofinger is like being dropped into the 19th century. Though popular with visitors, it is still a predominantly French clientele; every French President has been a regular here since the mid-19th century. Three-course menus from €35.

Le Train Bleu

Don’t choke on your foie gras as you admire the unbelievably lavish decoration of this fin de siècle brasserie. A railway cafe with a difference in the Gare de Lyon, Le Train Bleu is the most glamorous brasserie in Paris, a riot of decorative excess, all gilded swirling shapes and naked swooning figures. Two-course menus from €49.

Go

Musée d’Orsay

Impressionists and Post-Impressionists gives us a ring-seat at the Belle Epoque. €16.

Musée Carnavalet

Dedicated to the history of Paris, its stunning collection uncovers the social and aesthetic revolution of the Belle Epoque. €13.

The Comédie Francaise

Tours of the theatre to which Bernhardt was connected for much of her life are offered on Saturday and Sunday mornings. €15.

Paris Garnier Opera

Completed in 1875, the Paris Garnier opera house is open 10 to 5 every day, except matinee days, for self-guided tours €14.

Le Petit Palais

The exhibition, Sarah Bernhardt, And the Woman Created the Star, runs until August 27. €15.

Stanley Stewart travelled to Paris as the guest of Kirker Holidays. Three-night itineraries, including Eurostar tickets, private transfers, B&B accommodation, a Paris Museum pass, and tickets for the Sarah Bernhardt exhibition, start from £1,149 per person staying on the Right Bank in the Hotel Castille or from £1,440 per person staying on the Left Bank at the Pavillon Faubourg St Germain. In August, Kirker clients can enjoy an additional night at no extra cost. 020 7593 2288.