The Pandemic Has Had A Devastating Impact On The Future Of Women's Health

On March 30, 2020 - one week after Boris Johnson declared a nationwide lockdown - 25-year-old charity worker Sarah Lambrechts dropped to the floor in floods of tears as she received the call she had been dreading.

It was her hospital on the other end of the line, apologetically informing her that a surgery to remove the layers of endometriosis, that were like a thick spider's web enmeshing her internal organs, scheduled for two days time on April 1, was to be postponed indefinitely due to the unfolding Covid-19 pandemic. Sarah had already packed for the hospital, undergone the pre-op tests and mentally prepared herself for the procedure after 13 years of suffering and one year on the waiting list. 'It was what I'd been clinging on to for years, it felt like my tiny light at the end of the tunnel was being taken away from me,' she tells us.

Sarah respected and supported the need for a pause in elective surgeries, given the NHS were dealing with an emerging catastrophe, without enough PPE to cater for even their doctors and nurses, many of whom became infected and some who later fell fatally ill. She was aware that medical staff were having to relinquish their specialisms in order to treat patients in A&E who were struggling to breathe. She has a mother who still works as a nurse in the NHS so she understood the predicament more completely than many others. But it was just, such cruel timing.

'When I'm having a good pain day, I try to put things into perspective: people across the world have been impacted by Covid in a worse way than I have,' she explains. 'But, on a day in which the pain is bad, I'm depressed. My life feels like it's on hold. Like I'm just waiting for a series of letters to tell me where and when I need to be somewhere. It's difficult to accept, as someone who's supposed to be in the prime of my life.'

Sarah's symptoms started when her periods did. Her mother once had to break down the door of a Manchester café toilet after a 12-year-old Sarah had fainted on the loo from overwhelming pain. Within the next 10 years, as symptoms worsened and being rushed to A&E became a regular occurrence, Sarah was wrongly diagnosed with IBS, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and fibromyalgia, before finally being considered for endometriosis in 2017. Endometriosis has made recent headlines, for the fact that it takes an average of eight years to diagnose. Despite affecting one in 10 women, it's a condition which is still inexplicably misunderstood, and for which research has been scarce and ill-funded. A 2020 inquiry by the All-Party Parliamentary Group on endometriosis noted that there has been no improvement in diagnosis for the condition in a decade.

Of course, endometriosis is just one of many conditions for which patients have experienced delayed or cancelled treatments thanks to the pandemic. Even some organ transplants were put on hold. But given that conditions affecting women and people with uteruses - like PCOS, menopause and fibroids - constitute an area of medicine which, pre-pandemic, was already severely underfunded, under-resourced, riddled with taboo and in many cases, completely overlooked, the further setbacks caused by Coronavirus are huge cause for concern.

The worrying state of women's pain pre-pandemic

Women suffer pain disproportionately. This much we know. It's an idea manifested often in pop culture. In a 2019 episode of Fleabag, Kristen Scott Thomas delivers a searing monologue to Phoebe Waller-Bridge's character about the 'life of pain' that women put up with, from periods to childbirth to menopause. The topic was revived in the news earlier this year, when journalists Caitlin Moran and Naga Munchetty discussed their traumatic experiences of having an IUD fitted, calling for women to be offered pain medication during the procedure as routine.

That women's pain is unequal is an idea supported by science too. A 2016 meta-analysis published in the British Medical Journal found that chronic pain affects women more than men. Women are also less likely to be offered pain medication than men, despite presenting with the same level of pain intensity, a 2008 American study found. The 2017 Public Health England profile reported that while women live longer than men, women spend more years in 'poor health' than men (2.9 years longer). Of course, this is not to discount the many areas of health in which men are disproportionately likely to suffer. As well as shorter life expectancy, rates of suicide, Parkinson's disease and skin cancer are higher in men. However, these things are at least identified and, for the most part, benefit from the due medical attention. There is a gender health gap which discriminates against women, notably when it comes to research and investment.

The research gap

According to the charity Wellbeing of Women (WOW), just 2.1% of all publicly funded research is dedicated to women's reproductive health and childbirth, despite women making up 51% of the population.

'Many common women’s health conditions that affect millions of women including heavy menstrual bleeding, endometriosis and the menopause, receive little funding when it comes to research,' explains the charity's CEO Janet Lindsay.

When it comes to medical trials for conditions which affect both men and women, there's severe disparity too. 'Equality between the sexes is necessary in clinical research but trials are still unrepresentative. For example, heart and cancer trials are still male dominated, even though women are equally affected by these diseases,' says Lindsay. 'We propose that all clinical trials should reflect the prevalence of the sex in a particular disease. Ethnicity of disease should also be proportionately reflected in clinical trials.'

This lack of research has a knock on effect for the way that health professionals view women's pain, as they may not be educated about conditions which have not been scrupulously studied. For instance, the slow diagnosis of endometriosis has been attributed to women's pain being dismissed by GPs, friends and family, abetted by overstretched NHS gynaecology departments. Long waiting lists for gynaecology appointments existed well before the pandemic, as is evident by the year-long stretch before Sarah's scheduled surgery, despite her having been diagnosed with stage four - the most severe form of endometriosis.

'My surgeon has said [the delays are because] there are so many people that suffer with endometriosis versus the number of surgeons who are actually qualified to treat it,' Sarah explains. 'Because it's viewed as an elective surgery, it's not seen as a priority for the NHS, which I understand, but as I've gotten older my endometriosis has dictated my life. I've been at friends' weddings and have had to run back to my hotel room and lie down because everything hurts. There's a massive misconception that it is just my period - five to seven days of the month and then it's done - but it actually affects everything, all the time.'

How Covid hit women's waiting lists the worst

'Sadly, women are being left to suffer with painful symptoms for longer than they should,' Dr Edward Morris, president of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) tells ELLE. 'Gynaecological waiting lists were growing before the pandemic, with many people waiting for essential care... The knock on effect of these long waiting lists is the risk of women developing accompanying psychological problems. Gynaecological conditions can impact a person’s physical and mental wellbeing, and symptoms can drastically reduce a person’s quality of life. Chronic pelvic pain associated with conditions like endometriosis affects women’s ability to be mobile, their employment, and their relationships. The longer women have to wait for surgery, the longer it will be before they can access treatment to improve their quality of life, which can be very stressful and upsetting.'

The pandemic has had a detrimental effect on waiting lists across all departments, with the BBC reporting that five million people in the UK are currently waiting for procedures. This is due to staff being redeployed, or off sick, and resources from beds to theatre space being distributed across departments. Non-Covid conditions, particularly time-sensitive illnesses which can be fatal if left for too long like cancers, are understandably prioritised over benign (non-cancerous) conditions.

Gynaecology is one of the most heavily affected departments for these NHS backlogs, with the number of people waiting to see a gynaecologist increasing 34% in the last year, according to The Telegraph. Dr Morris explains that because of the existing long waiting times for gynaecology pre-Covid, the department has been 'disproportionately' hit by the Covid-19 backlog and 'more women are waiting for care now than pre-pandemic'.

'It's a health system which historically has not been good at listening to women and responding to their needs,' Dr Morris explains. 'Women’s health has been worst hit by the pandemic, from waiting much longer to be diagnosed or treated for benign gynaecological conditions, through to facing extensive waiting lists to access fertility treatment.'

But more than this, Dr Morris continues, 'There is a big concern that women’s experiences will not be properly heard as the NHS recovers from the pandemic, and that gynaecological waiting times will worsen, as other areas improve.'

Sarah has felt particularly lost during the last year and a half, with her surgery delayed, unable to even see a GP and fearful of going to the hospital at the height of the virus outbreak.

'I feel like I've been left in the dark. I just had to figure it out,' she says. 'What was I meant to do if I had a really bad flare up of my symptoms? I was too scared to leave the house, let alone to go to A&E or a walk-in clinic. If you don't know what to do, and you're just waiting around, it's horrible.'

The inequalities that Covid has laid bare

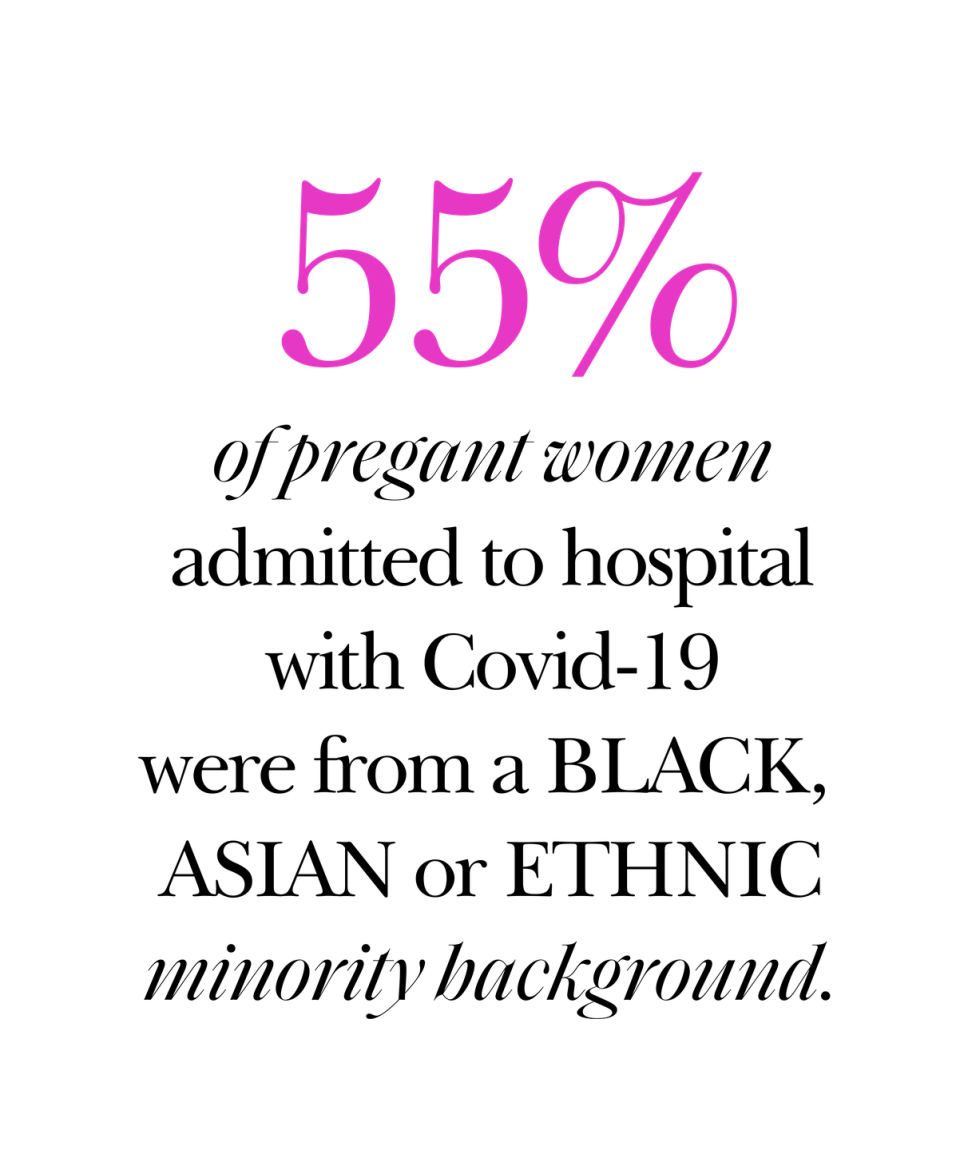

While women's health as a whole is faring badly, within it, there are further inequalities. In May 2020, it emerged that 55% of pregnant women admitted to hospital with Covid-19 were Black, Asian or minority ethnic. Dr Morris says the RCOG are concerned 'the pandemic has widened health disparities for women of these backgrounds,' and both the organisation and WOW note that a lack of research 'into ethnic disparities in healthcare in the UK' means that reasons for this increased risk of hospitalisation are unknown.

That there is an issue around pregnant women and coronavirus comes as no surprise, considering that there are always problems with healthcare for pregnant women. There has been a serious lack of representation for pregnant women in clinical trials, with so many barriers to entry. What this means, is that pharmaceuticals are rarely cleared for use in pregnancy, due to a lack of evidence either way regarding their safety. It is for this reason that pregnant women are often told they can take paracetamol and nothing else, until they've given birth. Both the RCOG and WOW support the inclusion of pregnant women in trials, citing the confusing public discourse surrounding pregnant women receiving the Covid-19 vaccine (in July 2021 England's chief midwife stressed the importance of pregnant women getting their vaccine after it emerged 98% pregnant women in hospital with Covid-19 were unvaccinated).

'The initial exclusion of pregnant women from COVID-19 vaccine trials made women vulnerable to more severe complications in later stages of pregnancy,' says Lindsay. 'Even though the COVID-19 vaccine is now recommended for pregnant women, many are reluctant or hesitant to take it up.'

Has Covid delayed future breakthroughs in women's healthcare?

Owing to limited public funding, research for women's healthcare is largely reliant on charities, who have been hit catastrophically by the pandemic. With the absence of fundraising opportunities, because of social distancing restrictions, and people finding themselves in tighter financial situations due to the economic effects of the crisis, it's estimated that medical research charities in the UK have lost at least £292 million in income over the last year and a half.

WOW have said their income was decreased by 50% since the pandemic began. Considering they fund a huge bulk of the research into women's health issues - such as current ongoing studies on the first non-hormonal treatment of endometriosis via an anti-cancer drug - the idea that future breakthroughs may be delayed due to the slump in funding is a valid concern.

On the plus side, the RCOG cites several breakthroughs in reproductive healthcare which have actually been aided by the pandemic. The first is the at-home abortion pill which makes early abortions more accessible for women who need them. The second is the advance of the over-the-counter contraceptive progestogen-only (mini) pill. Both of these, Dr Morris says, create 'easier access to essential health services'.

So, what now?

What can be done to rectify the negative effect of the pandemic on women's health? This month, the Prime Minister increased the national insurance tax specifically to address the health backlog caused by Covid-19, though this was met with controversy, with some saying the lowest-earning workers would be hit hardest, rather than the wealthy. But, even if this tax increase is being ring-fenced for the NHS, how do we ensure enough public funding is used to improve care and treatment specifically for women's health issues?

'To continue to make breakthroughs in women’s health, we are calling for more funding, greater prioritisation on the public health agenda, and more collaboration between the Government, research bodies, and other key partners,' says Lindsay.

'It is vital that women are not ignored,' stresses Dr Morris. 'They should be given fair access to resources within the existing health system to counteract the impact of the pandemic. We want to be able to ensure women receive the support they need in a timely manner once we come through the other side of this pandemic.'

For Sarah's endometriosis surgery she has been advised that, because of the backlog, the waiting time could be a further 12 to 18 months, and she is one of many women up and down the country who will be going through this.

'Reducing waiting lists will help women access care to improve their quality of life, and reduce the event of women experiencing prolonged and painful symptoms,' says Dr Morris. 'It is also essential that women who are on waiting lists are regularly communicated with about how long they will likely wait for treatment, and that those whose symptoms are worst are prioritised. We want to ensure that women who are experiencing painful symptoms are seen as quickly as possible once services return to normal.'

In March, the department of health issued a call for evidence on women's health, asking women, charities and organisations to share their experiences with the aim of informing the government's 'women's health strategy'. The consultation is currently closed, so only time will tell if the government will finally do an about turn and actually listen to the rally cries of women across the nation. The future of women's healthcare likely depends on it.

You Might Also Like