Palm Springs Chic? How ’50s-Era Desert Modernism Is Being Adapted for Modern-Day Living

The birth of desert modernism can be traced back to some fine print. In the early and mid-20th century, Hollywood’s rigid studio system reportedly kept some of its biggest stars contractually bound to remain within a two-hour drive from the set during production, and within that roughly 120-mile radius there was no more appealing escape than Palm Springs. In response to an influx of high-profile, creative, and free-spending clientele—everyone from Cary Grant to Frank Sinatra—a distinct style of architecture that had first emerged in the 1920s suddenly exploded in the 1950s, transforming the once sleepy city of dude ranches and date farms into the original celebrity hideout.

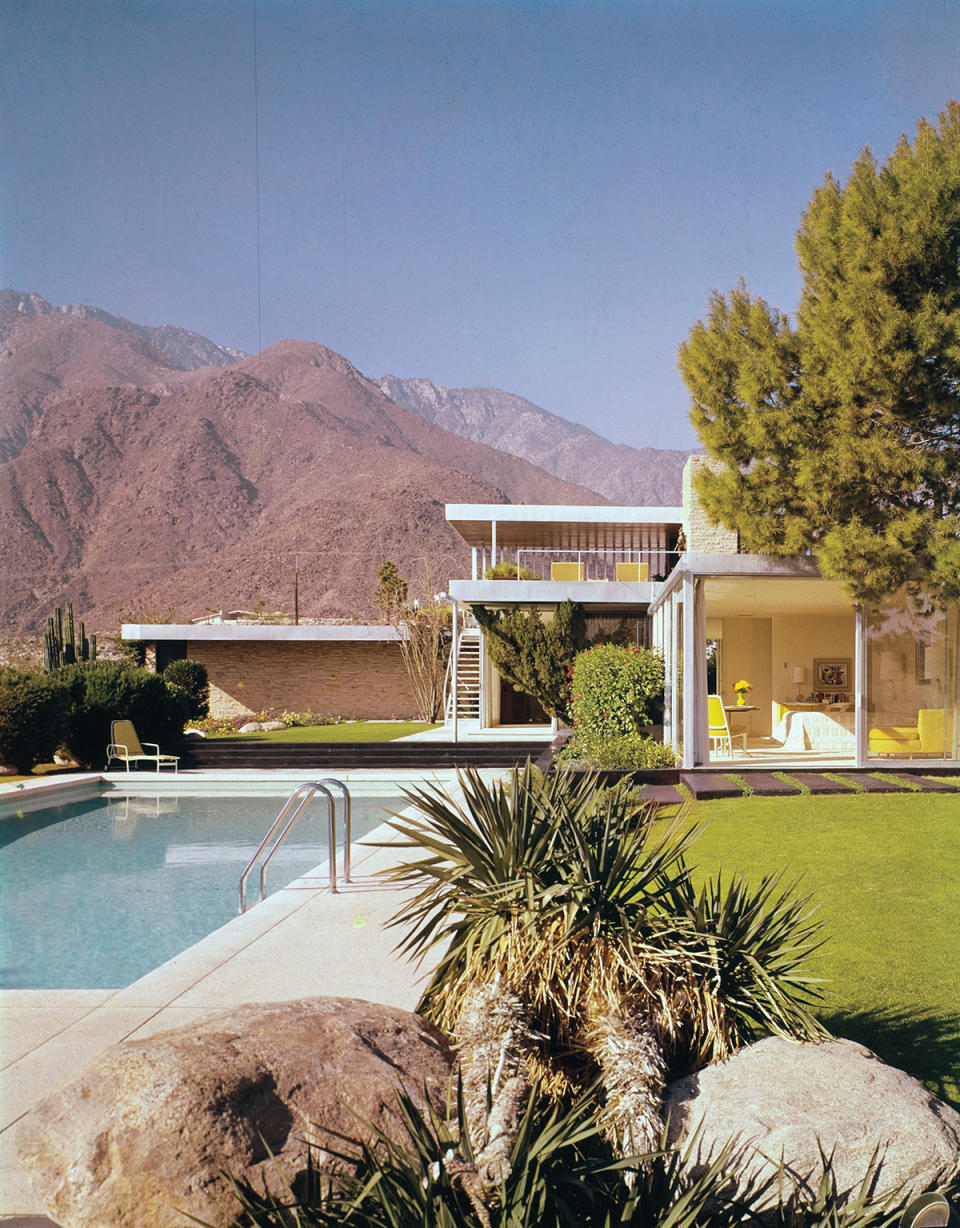

Inspired by the relentless sun and the open, arid landscape, a group of pioneering architects responded with innovative designs rooted in modernist sensibility. The result was a wave of homes defined by a smooth transition between indoors and outdoors, with walls of windows to frame the dramatic views. Other signatures included earth-toned palettes, the use of natural, local materials, breeze-block walls for shade and privacy, and low, flat roofs that allowed the structures to blend into the surrounding environs.

More from Robb Report

The secondary nature of these new homes (they were originally envisioned as retreats for the winter months) made clients more willing to experiment. It was a fortuitous turn for architects such as William Francis Cody, Albert Frey, and, perhaps most famously, Richard Neutra, who were all looking for an opportunity to implement the layouts and materials that came to exemplify their visions of modernism. Today, studios are looking to expand on that legacy while continuing to push the definition of desert modernism in the Coachella Valley.

“For us, the design inspirations do really come from the architects who were building here previously, particularly Richard Neutra and Albert Frey,” says Sean Lockyer, founding principal of Studio AR&D Architects.

Lockyer’s residential projects across Rancho Mirage and Palm Springs draw on that rich history while utilizing the most cutting-edge materials and design processes available today, all in the service of creating that seamless flow between a home and the surrounding land. “We’ve been able to embrace the way Frey incorporated boulders in some of our projects, designing around really massive boulders, working them into the pool area, or slicing them and applying them to walls,” Lockyer explains. Relying heavily on concrete and steel—both traditional desert modernist materials—allows Lockyer to bring high-tech weatherproofing to his designs, as well as finishes that feature intentional imperfections. While keen to celebrate original desert tropes, Lockyer notes that today’s clients prefer homes that are easy to keep up. “We want maintenance-free materials,” he says, “but we don’t want to powder-coat everything or for anything to look plastic.”

Green design, including energy efficiency, is another area where architects are evolving the legacy of desert architecture. “Original desert modern houses were extremely inefficient, with single-pane windows and doors,” says Philip Monaghan, a board member of Preservation Mirage, an organization dedicated to promoting and protecting the architectural history of Rancho Mirage.

Alex Penna, principal at Studio Khora, likewise stresses the key role sustainability plays in desert design today. “The rules of modernism include using contemporary technology, but there’s a huge difference between what that meant then and what it means now,” he says. This year, Penna plans to start the build on a Coachella Valley Glass House focused on innovatively recycled materials, such as hemp used for insulation.

Lockyer, for his part, has built upon the breeze-block idea by turning, instead, to rain-screen systems most often seen on the East Coast. “They work well in rainy Philadelphia but also in a desert environment,” he says. “You’ve basically suspended an umbrella over the entire building so the heat impact is broken, and you get a ventilated space that can cool the facade.”

Inside, there’s a similar reverence for the original juxtaposed with new approaches that allow for more freedom and a blending of styles. “We’ve seen a move away from campy, ’60s cliché decor, with people turning towards modern furniture that nods to midcentury but isn’t enslaved by it,” Monaghan says. “Now, it’s a little bit more recycled, more sustainable, with lots of natural materials and upcycled fabrics—people putting orange and turquoise all over their house is pretty much gone.” For Lockyer, that means weaving in midcentury influences, but not at the cost of an uncomfortable layout or a forced piece of period-exact furniture. “We try to mix both—people used to be very strict in adhering to history, and I feel like now that’s loosened up quite a bit.”

As Penna sees it, the mission statement of contemporary desert is both straightforward and powerful. “If [architects like] Neutra were alive, what would their homes look like today? That’s what we want to do—pick up from where they left off.”

Best of Robb Report

Sign up for Robb Report's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.