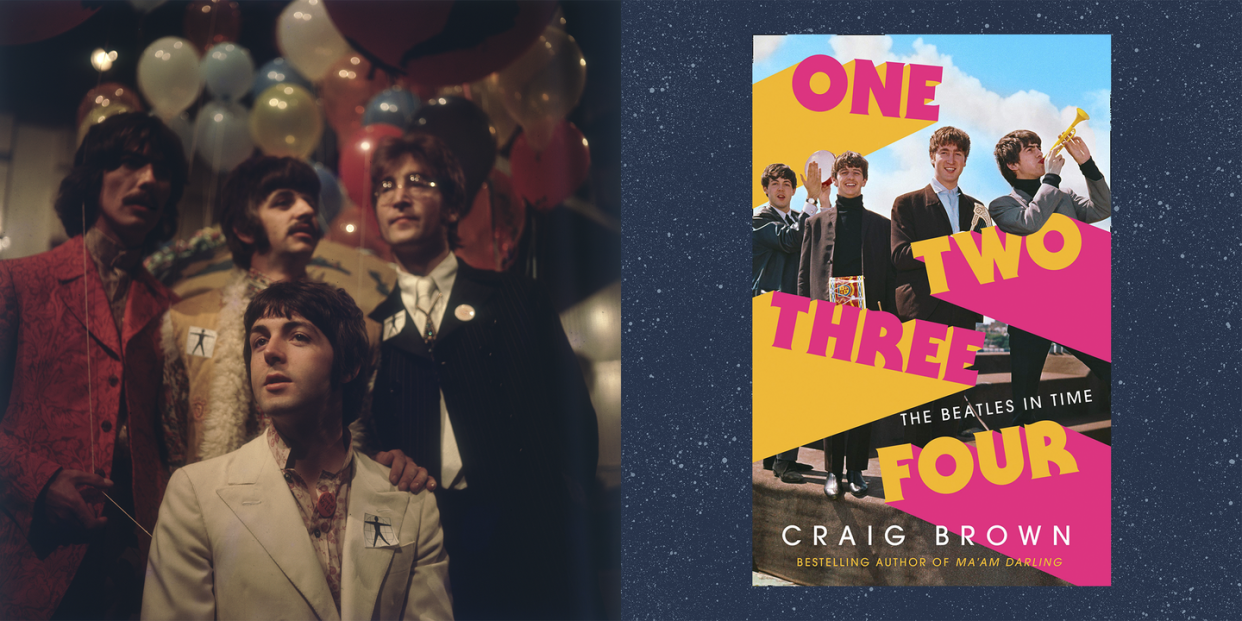

'One Two Three Four: The Beatles In Time': As Dark And Sunny As A Lennon/McCartney Song

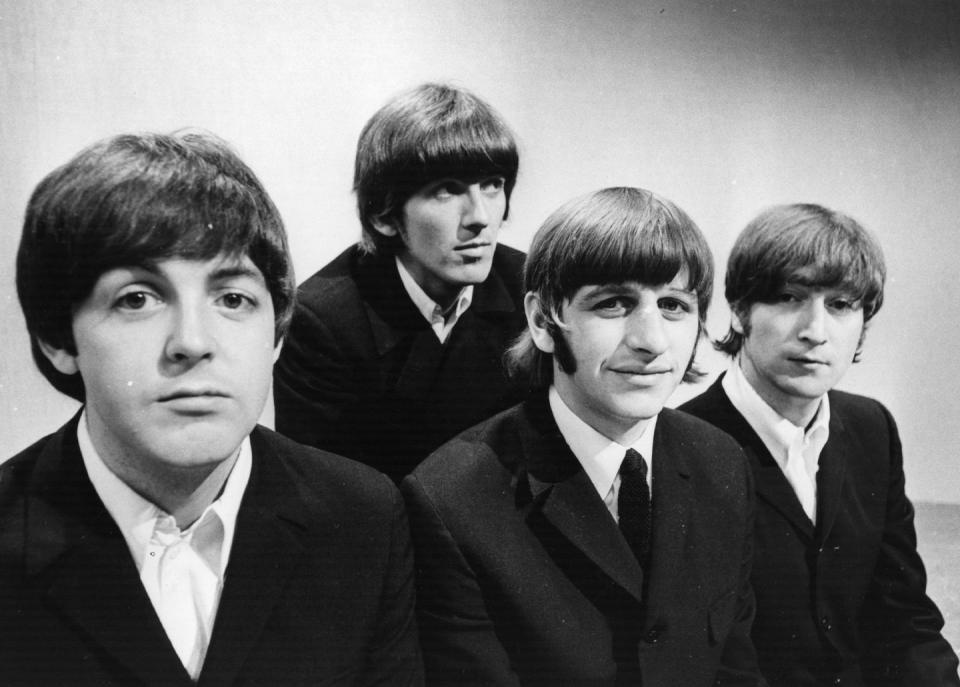

“When we talk about The Beatles,” writes Craig Brown, “we talk about ourselves.” For an international phenomenon, The Beatles were peculiarly, cussedly English. The most significant band in the history of pop, they are key figures in the past half-century of our nation’s public life, as well as in the dream lives of its citizens. The Beatles entered our bloodstreams, collective and individual, and they pulsate in them still. They were modernists, agents of change, forging the future, and they were preservationists, forever harking back to the past, real and imagined, England’s and their own.

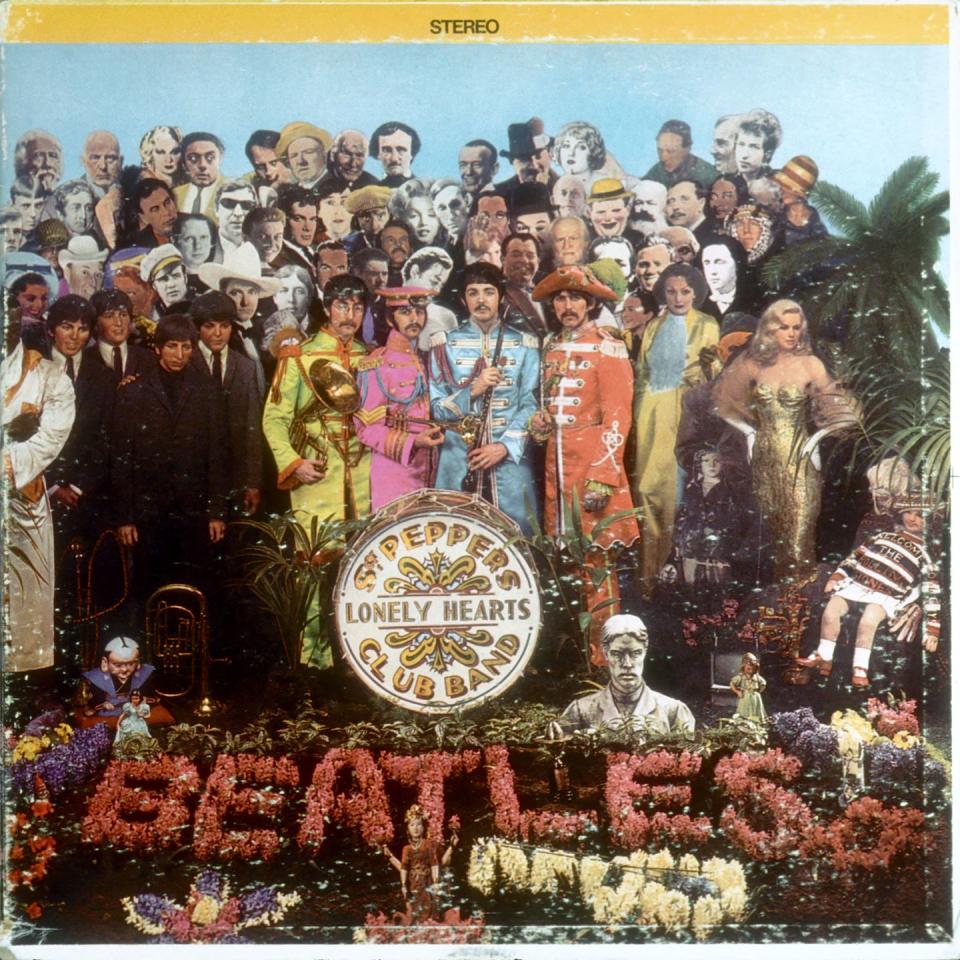

Their most forward-and-at-the-same-time-backward-looking album was Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, released in 1967. It was, writes Brown, “an exercise in playing about with the past.” Readers of Brown’s might understand why this would appeal particularly to him, as a writer determined to make sense of British popular history, or at least to explore it, by reinventing the method of its delivery.

Parodist, critic, author of the peerless Private Eye “Diary”, Brown is also a Beatlemaniac. For those of us who are fans of his stuff, as well as devotees of The Fab Four, the news last year that He was working on a new book about Them sounded like a celestial combination of writer and subject. The result is the terrific One Two Three Four: The Beatles in Time.

Brown’s previous book, the cunningly structured Ma’am Darling: 99 Glimpses of Princess Margaret, was what he called an “exploded biography”. It was a demolition of the form, abandoning traditional narrative biography, with its slow and steady slog through the past, for a cut-and-paste approach, gathering discreet shards and fragments of history — anecdotes, lists, photographs, snatches of dialogue, contemporary reports, interviews — and assembling them into a collage of memories and weird connections and jokes and sardonic footnotes. The accretion of detail built to a portrait more revealing, certainly in terms of contemporary atmosphere — the temperature of the times — than that typically offered by traditional biography. Funnier, too.

One Two Three Four, published to coincide with the 50th anniversary, on 10 April, of the break-up of The Beatles, is an exploded biography of the band. It is a critical appreciation, a personal history, a miscellany, a work of scholarship and speculation, and a tribute. It contains knockabout first-person reporting from Liverpool and Hamburg, as well as frequent authorial interruptions for personal anecdotes: trips to the panto, boarding school memories. Multiple conflicting accounts of a single incident — a punch-up at a party, say — illustrate “the random, subjective nature of history, a form predicated on objectivity but reliant on shifting sands of memory,” and make explicit Brown’s critique of straight biography.

“In an earthquake,” Brown quotes Paul McCartney as saying, “you get many different versions of what happened by all the people that saw it. And they’re all true.”

There is no shortage of eccentric books about The Beatles. The canonical ones — Ian MacDonald’s ecstatic Revolution in the Head, Mark Lewisohn’s epic work-in-progress, All These Years — are, if anything, even madder than fan fiction, testaments as much to their authors’ completist obsessions as to the band’s undeniable greatness. One Two Three Four is no less serious in intent, but far less po-faced.

Brown hits all the beats you might expect from a Beatles biography, from jagged first stabs through the swelling roar of the Beatles’ imperial phase to the sour diminuendo of the band’s dissolution. But he places at least as much emphasis on what may seem inessential, tangential, ephemeral, as he does on the big stuff.

So, there are walk-ons for Bob Dylan and Muhammad Ali and Mick Jagger and the rest of the Sixties crowd. Familiar names from the story are sketched: Pete Best, replaced by Ringo just weeks before The Beatles made it big; Stu Sutcliffe, the Beatle who stayed in Germany, and died; the brilliant Brian Epstein; John’s imperious Aunt Mimi. Less predictable appearances are made by Malcolm Muggeridge — he met the pre-fame Beatles in Hamburg and recorded, in his diary, “their faces like Renaissance carvings of saints or Blessed Virgins”, which doesn’t quite chime with other reports from the Reeperbahn — and Peter Stringfellow, who managed to stretch to £85 to book the band for The Black Cat Club, Sheffield.

Brown finds time to consider the ragtag cranks and crooks who jumped on The Beatles bandwagon. We meet “New Jersey bruiser” Allen Klein, a man described as “having the charm of a broken lavatory seat”, as well as “needy” drugs squad detective Norman “Nobby” Pilcher, “a bumbling avenging angel”. We say hello-goodbye to the preposterous “Magic” Alex, “for whom no job was ever too large to be started or too small to leave unfinished”. We hear the sad story of The Singing Nun, and the heartbreaking tale of Jimmie Nicol, “too forgotten a figure even to feature in roundups of forgotten figures”. Nicol was the Beatles’ tour drummer for 13 life-ruining days, while Ringo was indisposed.

We enjoy the spectacular folly that was The Beatles’ business, Apple Corp. “The weirdness was not controlled at the start,” lamented Beatles’ press officer Derek Taylor, before noting, sagely, that, “You can’t control weirdness, anyway; weirdness is weirdness.”

Brown glories in the absurdist details. George’s description of acquiring a taste for the finer things as “branch[ing]out into the avocado scene.” Ringo’s explanation for the failure of his building company: “No one wanted to buy the houses we put up.” Animals frontman Eric Burdon’s eye-opening explanation of how he came to be — or so he claimed — the Egg Man in “I am the Walrus” (chapter 105, I’m not quoting it here). John’s absentee father coming to a fancy-dress party in costume as “My Old Man’s a Dustman”, in clothes he had bought from a real dustman for £5, earlier in the day. “He literally reeked of garbage,” remembers a guest. John’s reason for funding Yoko Ono’s exhibitions at the Lisson Gallery: “With women like that you have to pay them off, or they never stop pestering you.”

It will come as no surprise to readers of Private Eye that Brown has great sport with Ono especially, counterpointing her gnomic recent Twitter posts with the songs of Shirley Temple, whom she apparently once impersonated as a child, and imagining her “poetry” as if it had been rewritten by Ringo. (“Ringo” means “Apple” in Japanese, says Brown.) One suspects that an exploded biography of Ono alone — a solo Ono — might be a profitable next volume for Brown. The unsparing depiction of John and Yoko’s self-serving social activism is pretty devastating.

There’s also some astute writing about academia’s doomed attempts to parse the lyrics of the band’s greatest songs. “Lyrics removed from music,” explains Brown, “are like fish removed from water.” Take that, Christopher Ricks. Nowhere can the difference between the reverent US and the irreverent UK music press — such as they were — be better illustrated than in their respective reactions to Lennon’s nightmarish “Revolution 9”, from The White Album. Take your pick from “an aural litmus of unfocused paranoia” (Rolling Stone) or “a pretentious piece of old codswallop” (New Musical Express).

By quoting liberally from the testimony of those who were teenagers as the time — the young Bruce Springsteen, the young Tom Petty, the young Chrissie Hynde — Brown gets at the extraordinary, life-changing effect The Beatles had, an effect unprecedented and unrepeatable, at least by a pop group. (Other messiahs are available.) Older establishment figures were bowled over, too. Poor Leonard Bernstein was reduced to Jabberwocky gibberish, hymning “the frabjous falsetto shriek-cum-croon, the ineluctable beat, the flawless intonation”, and on and on and on.

Not everyone was so fawning. Here’s Kingsley Amis, writing to Philip Larkin on 19 April 1969: “Oh fuck The Beatles. I’d like to push my bum into John L’s face for 48 hours or so, as a protest against all the war and violence in the world.” The splenetic Anthony Burgess was infuriated by the “twanging nonsense” of The Beatles’ music.

A chapter is devoted to letters from fans, such as this one:

Dear Beatles,

I told my mother I can’t imagine a world without The Beatles, and she said she could easily.

Loyal forever,

Lillie K,

Fairbanks, Alaska

Another chapter records America’s Billboard Hot 100 singles chart from the week of 4 April 1964. The Beatles have the top five spots plus seven more. Still another reprints a guest list, published in 1966 in Queen magazine, from the opening night of Sibylla’s discotheque in Swallow Street, Mayfair. Lots of hip counterculture stars, a few louche aristos, and Nigel Dempster.

A chapter is devoted to misheard lyrics: “And when I get home to you, I find a broken canoe.” Brown considers the pathology behind Lennon’s compulsive punning, and how it informed what Bruce Springsteen has called, quite reasonably, “the worst and most glorious band name in all rock ’n’ roll.”

There are many such cherishable asides. I enjoyed Pattie Boyd’s take on Haight-Ashbury, hippy ground zero, during the Summer of Love, 1967: “Horrible — full of ghastly drop-outs, bums and spotty youths, all out of their brains.” Which makes her sound more like Princess Margaret than a groovy Sixties swinger, and earns her bonus points for hypocrisy, given she was herself tripping on acid at the time.

There is lots of stuff on teeth, including the following truism: “No one wants a groovy dentist.” There is still more on hair. We learn that at Christmas 1964, when he was seven, Brown was given a Beatles wig by his parents. We learn, too, that 20,000 Beatles wigs were being sold each day at that time, in New York alone. And that Earl Mountbatten of Burma spent Christmas Day prancing about Broadlands, his Hampshire home, wearing an imitation mop-top on his head.

One reading of the Princess Margaret book is as a psychodrama about the toxic effects, on a person constitutionally ill-equipped to deal with them, of unearned privilege and prestige. The Beatles book might be seen as a similar take on the effects on a parade of characters, the four principals and those who came into their orbit, of a global fame and corresponding hysteria that even the Queen’s sister would struggle to recognise. It was John Updike, a Beatles fan, who remarked that celebrity is a mask that eats into the face. “Weirdland,” is Ringo Starr’s term for the world that the mega-famous inhabit, where even members of their close families treat them like royalty.

One Two Three Four notes the corrosive toll, physical and psychological, that fame took on the four boys from Liverpool, perhaps especially on John, always the most caustic and ill at ease, increasingly the most difficult. The others coped in their own ways. George sought enlightenment, and escape, in Eastern spirituality. Ringo dealt with fame with, for the most part, self-deprecating good humour, not always succeeding in covering up the mixed blessing of being seen as the least talented of the four. Paul seemed to have the least complicated relationship with his success. Others — notably Brian Epstein — didn’t cope. In August 1967, the “Beatle-making Prince of Pop” took an overdose of sleeping pills and died in his bed. He was 32.

Like Ma’am Darling, and like life itself, One Two Three Four is a tragicomedy. Both dark and sunny, like a Lennon/McCartney song. From Chapter 11: “In 1964, John Lennon advised the Beatles’ press officer, Derek Taylor, against eating the cheese sandwiches at Speke Airport. He had once been employed at Speke as a packer, he told him, and he used to spit in them.

“In spring 2002, Speke Airport was renamed Liverpool John Lennon Airport…”

One Two Three Four: The Beatles in Time by Craig Brown (Fourth Estate, £20) is out now.

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more delivered straight to your inbox

You Might Also Like