‘Nowadays, everyone is in the paparazzi’: DeuxMoi, rumours, and the murky ethics of Instagram gossip accounts

What did Andrew Garfield order at Starbucks on Tuesday? Where did “the tall hot one from The 1975” make out with a redhead? How much did Dennis Rodman tip a drag queen last week?

Unless you’re friendly with any of the aforementioned celebrities, or happen to have recently stumbled across them in public, these are not questions to which you should know the answer. And yet, if you follow @deuxmoi on Instagram, such tidbits offer a mere snapshot of the kind of information you will be given on a regular basis, often alongside photographic evidence.

DeuxMoi is a crowdsourced gossip account that shares anonymous submissions and celebrity sightings on its Stories. In theory, all of it disappears after 24 hours – except it doesn’t, because almost everything that’s posted gets screenshotted and lives on for ever in news articles and on WhatsApp groups.

DeuxMoi isn’t alone in forensically examining the lives of the rich, famous, and often rather boring. There’s the newsletter Popbitch, which covers political and pop-cultural gossip; Diet Prada, famed for calling out misconduct in the fashion industry; and a blog called Tattle, which focuses on social media influencers. The information shared can range from which Hollywood A-lister has been cast in a new Marvel film, and who is a nightmare to work with, to which musician makes wild demands on tour and which famous model allegedly had a threesome with a certain celebrity couple.

Generally speaking, these accounts are run by people who prefer to stay anonymous themselves. Launched by two women in their twenties in New York City, the DeuxMoi account was originally used as a fashion blog until 2020, when one of the account holders started asking its followers for celebrity gossip. She was inundated with stories. Within just a few months, DeuxMoi had acquired hundreds of thousands of followers. Today, just one of the founders is thought to be in charge of the account, and while rumours of her identity have percolated online since last summer, who she is remains a mystery.

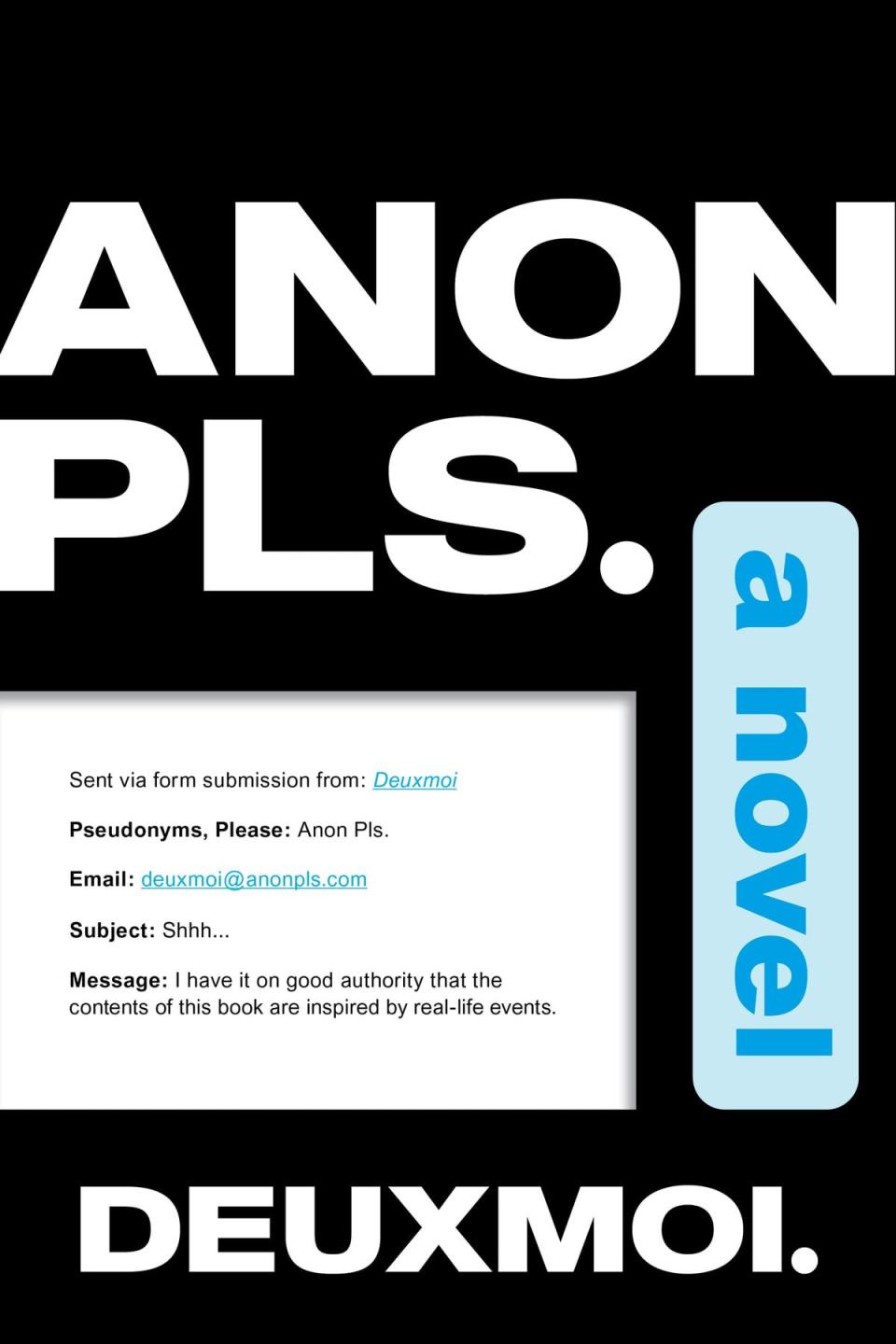

Nonetheless, with 1.9 million Instagram followers (who include many of the celebrities it posts about), DeuxMoi has grown exponentially since the pandemic. In addition to the Instagram account, there’s now also a podcast, a newsletter, a novel, merchandise, and even an HBO drama in the works. Celebrity gossip is becoming an omnipresent social and cultural force.

We are encouraged to see celebrities as ideals and as flawed, imperfect individuals – this ensures that fans enjoy their successes, but perhaps enjoy their mistakes and scandals even more

David Schmid, pop-culture expert

But as these platforms continue to grow, so does the scepticism around them. For some people, being featured on a gossip blog helps maintain their social and cultural relevance – Kim Kardashian, for example, once referred to DeuxMoi as “the bible”. For others, though, it represents an archaic and inappropriate degree of obsession that we should have left behind in the early Noughties.

“Whenever I feel like that line has been crossed in my life,” Florence Pugh said last year, “whether it’s paparazzi taking pictures of private moments [...] or gossip channels that encourage members of the public to share private moments of famous people walking down the street, I think it’s incredibly wrong.”

Adele has even joked about how the site has affected her personal life. “You can’t set me up on a f***ing blind date!” she told Rolling Stone in 2021. “I’m like, ‘How’s that going to work?’ There’ll be paparazzi outside, and someone will call DeuxMoi, or whatever it’s f***ing called! It ain’t happening.”

Some celebrities have even started responding directly to claims made against them. Take Girls5Eva and Dawson’s Creek star Busy Philipps, who, in November last year, hit back at an allegation on DeuxMoi that she was “rude and dismissive” behind the scenes of her namesake talk show, Busy Tonight. “Someone sent me this and it’s probably very true to many of the executives who were at the network then,” she wrote on her Instagram Story, before providing further context to the claim, noting how she had an ongoing issue with her team and has acknowledged this in depth on her own podcast and taken responsibility where appropriate. The DeuxMoi item implied Philipps was entirely at fault. “The idea that I was rude and dismissive is so steeped in misogyny it proves my f***ing point anyway,” she added.

The trouble with any kind of gossip is that the truth is only so important. The people running gossip accounts often remind their followers that everything they post is pure conjecture. But that doesn’t seem to stop the claims from entering into the mainstream media and generating worldwide coverage. And when a handful of DeuxMoi’s posts do wind up being confirmed as facts (the account was one of the first outlets to report on Kim and Kanye’s split, for example), it’s easy to assume that everything else could be, too.

“Although the disclaimers are largely meant to prevent legal action, the sentiment speaks to a larger issue in media culture with misinformation and disinformation,” says Dr Jenna Drenten, an associate professor of marketing at Loyola University Chicago, who studies how celebrities leverage social media. “Celebrity gossip accounts potentially normalise distrust in wider media, and consumers’ openness to misleading news.”

Despite this, DeuxMoi has become a go-to resource for showbiz journalists. “That’s why I started following it originally,” says Nelly*, who reports on celebrity news in her job as a writer. But she unfollowed the account after it shared information about someone she knew. “There’s a lot of things on there that I know are not true,” she says. “I was believing things that were toxic and offensive, with little evidence. These accounts curate the information they [receive], so they harness a lot of power over who gets bad versus good press. Today, DeuxMoi is in charge of the narrative for a lot of people.”

It’s a marked difference from old-school showbiz journalism, which relied on direct quotes and real-life conversations with sources. “We went out and partied, interviewed and got to know the celebs in question,” says Dean Piper, a former showbiz columnist turned celebrity PR. “Celebrities had leagues more privacy back then, and could essentially get about town without anything to worry about other than paps. Nowadays, everybody is a pap.”

That’s not to say that celebrities always garnered a greater degree of respect. There was the phone-hacking scandal, for example, and the media’s treatment of Noughties It-girls such as Britney Spears and Lindsay Lohan. But there seemed to be a period of progression afterwards that’s now been left behind.

“We wouldn’t have dreamed of taking pictures of people inside venues,” adds Piper. “And even if we did, it was on a disposable camera, and you’d have no idea what the results were until they were developed. Celebrity journalism moved slower, was more [considered] and, in my opinion, far more interesting to follow. It’s just chuck-away now.”

This attitude seems to be catching on among consumers, too, with some starting to question whether all the information we receive is even necessary. Do we really need to know what celebrities order in their local coffee shop, for example, or where they go to the gym? “The trivial and mundane aspects of celebrity life became entertainment during the pandemic,” says Drenten, noting that it’s no wonder DeuxMoi’s rise to prominence coincided with lockdown.

“We are encouraged to see celebrities as both ideals and role models and as flawed, imperfect individuals,” adds David Schmid, faculty expert on pop culture at the University of Buffalo. “This combination ensures that fans enjoy their successes and achievements, but perhaps enjoy their mistakes and scandals even more. The pandemic intensified this phenomenon, because when we were all in lockdown, we had more time to obsess over the lives of celebrities and participate in online fan communities. Following celebrities made many people feel less isolated.”

But perhaps there is a point where it goes too far. Some people have accused DeuxMoi of normalising celebrity stalking, for example. This is something Deux, as she refers to herself, has spoken out against, telling the Associated Press: “Sightings are not posted in real time ... I’m not trying to promote stalking celebrities. I want to make this very clear: my followers do not stalk celebrities. They just happen to be in the same place at the same time as a celebrity.”

But whether it’s minor or major, true or false, in real time or not, the amount of detail we’re being fed on a regular basis about celebrities is starting to feel tawdry. And the brouhaha surrounding totally unverified claims is being blown way out of proportion. Take the recent post on DeuxMoi claiming that Kylie Jenner and Timothée Chalamet are dating. The unsubstantiated rumour got the internet’s knickers in a twist, spawning countless articles and viral Twitter threads despite the fact that the stars have never even been photographed together.

“We know too much,” says Nelly. “Celebrities are entitled to private lives. I think the fact we don’t allow them that any more is why true stars, like those from the golden age of cinema, don’t exist [now]. We’re fed too much [and] that causes a never-ceasing appetite for more info, more gossip, more access. It’s a shame.”

It’s hard to fight a craving at the best of times, but particularly one that you keep on feeding. This is true of celebrity gossip. After all, DeuxMoi wouldn’t exist if people didn’t submit anything. Nor would it last if people stopped following. But they are submitting. They are following. And so the hunger continues. If anything, it’s more insatiable than ever.

*Name changed to protect identity