Nostalgia, remorse, and terrible tabloids: Why we’re all suddenly talking about the Noughties

We are in the midst of a historical throwback. Until recently, the period following the turn of the millennium was frequently dismissed as a pop-culture graveyard strewn with low-rise jeans, rhinestones, peek-a-boo thongs and poorly blended hair extensions. Barring a few acclaimed artefacts, the Noughties were considered by many to be a culturally unremarkable time to be alive, and any evidence of the era – largely documented on bubblegum pink Motorola Razrs – was better forgotten. Over the past couple of years, though, this has all started to change.

References to Noughties pop culture are becoming increasingly commonplace in the mainstream. Gen-Z (those born between around 1996 and 2010) are said to glamorise the era: binge-watching Friends, wishing they could have been teenagers at the time, and resurrecting its most dreaded clothing trends under the label of “Y2K fashion”. For millennials, internet meme spheres are awash with clips from Big Brother, Keeping Up with the Kardashians and Peep Show. This has only geared up during the pandemic; last month, we even got a Tracy Beaker special, which set social media alight.

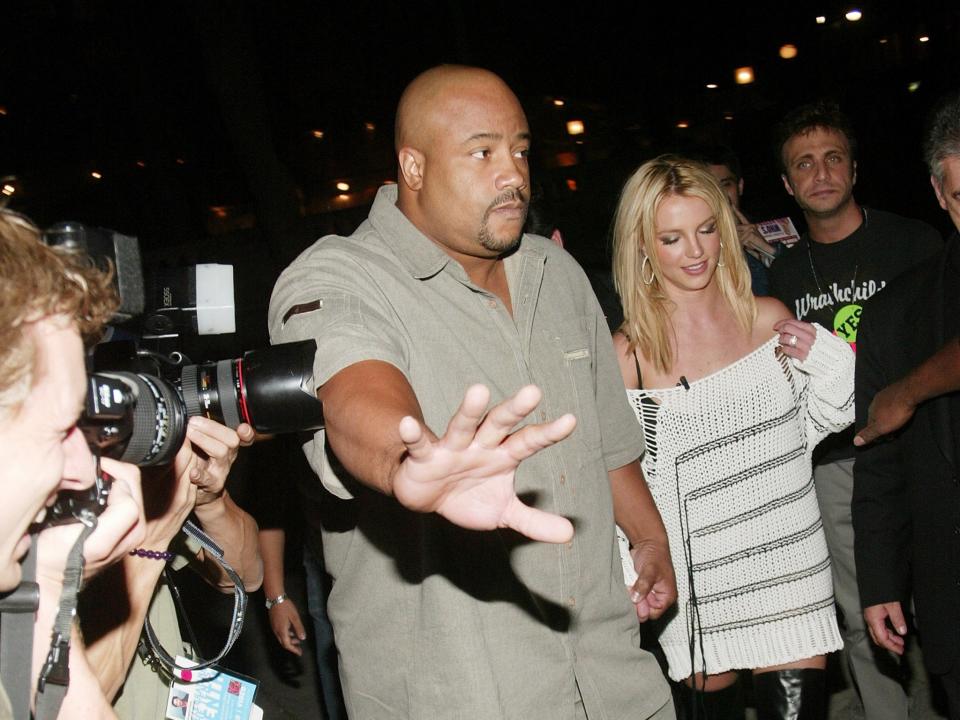

But as we reminisce about the Noughties, we are also reckoning with it. In 2019, we saw the release of a seismic three-part documentary series on Jade Goody, the reality star who lived her twenties in front of the camera – from her Big Brother debut to her death from cervical cancer in 2009. In December, the BBC aired the four-part series Celebrity: A 21st-Century Story, which charted the evolution of celebrity culture from the year 2000. And last month, Framing Britney Spears, a New York Times documentary on Spears’s mental health crisis and the subsequent Free Britney movement, sparked widespread conversation around the more morally dubious aspects of Noughties media production.

So why, in the early 2020s and in the midst of a pandemic, are we suddenly reflecting so intently on the turn of the millennium, and what can be learned from our current fascination with the Noughties?

“‘Zeitgeist culture’ is dominated predominantly by people in their twenties,” says Tara Joshi, co-presenter of Twenty Twenty, a podcast focusing on early Noughties pop culture. Joshi tells me that in essence, people love to indulge in the pop culture of their youth, and now, the children of the Noughties are old enough to influence mainstream culture.

Joshi’s theory also chimes well with the “20-year-rule” – which states that mass-market pop culture and fashion operate in cycles of around 20 years. As described by Simon Reynolds, author of Retromania: Pop Culture’s Addiction to its Own Past: the 1970s saw Grease and Happy Days stoke nostalgia for the Fifties, and 1990s rock and hip hop borrowed and sampled heavily from the music of the 1970s. Millennial nostalgia is part of the same trend, and it’s bang on schedule.

This makes Noughties culture profitable, says Joshi: “There’s a booming nostalgia industry.” She points towards the deluge of TV shows, fashion trends, articles and Facebook pages geared towards “1990s kids” in the 2010s. “This has been in force for a long time. But now, in particular, during a time when the future feels unwieldy, there’s something quite nice about sinking into the past.”

This is something streaming platforms in particular have capitalised on. Pre-pandemic, streaming platform BritBox launched, marketing itself as the home of British boxsets, while Friends and The Office were the most streamed shows on Netflix. As content production slowed down during the Covid-19 crisis, viewers were provided with more bingeable nostalgic comforts; Netflix acquired the first two seasons of Keeping Up with the Kardashians (shot in 2007-8) in June last year, and Amazon Prime added every episode of Paris Hilton and Nicole Richie’s The Simple Life the following month (which aligned nicely with promotion for This Is Paris – a new documentary focusing on Hilton’s life and rise to fame).

But these forces have also given rise to some more critical reflections on Noughties culture. Samantha Stark, director of Framing Britney Spears (which broke Sky Documentaries viewing records in the UK), tells me that she thinks the Covid-19 pandemic was part of the reason the documentary got the green light. “Since there is so little happening off the internet that we could film, we were looking for stories that could be based in archival footage,” she says.

Stark also tells me that both #MeToo, and the widespread conversations we’ve seen around mental health in recent years, offered the makers new and interesting lenses through which to analyse the media of the Noughties. “Liz Day [a senior editor at The New York Times, who came up with the idea for the film] wanted to look back at this woman who was vilified by the media through a 2020 lens… She suspected if we pulled out and gave context to the misogynistic media coverage, our entire view on Britney Spears would change. Boy was she right.”

“When I started interviewing people with first-hand experience working with Britney, I realised she was a creative woman who was very in control of her career and business as a young person. A mother who was going through a custody battle, possibly experiencing postpartum depression while essentially being stalked by dozens of men on a daily basis. A performer who made millions of dollars jumping through fire in Las Vegas but was deemed incapable of making basic decisions in her own best interest. There is a lot there to reframe.”

Stark adds that, just as many Noughties kids are bringing their nostalgia into the film and TV industries as adults, there are others who were deeply wounded by the decade and want to explore those scars. “People like me – who were teenagers when Britney rose to fame – people who witnessed the mean-spirited coverage of Britney as peers,” she says. “I’ve been doing a lot of re-examining lately about how this affected my development, and how it must have affected the development of the people around me of all genders. Now that we’re a lot of the people in charge of the media, I think we want to do things differently.”

As documentarians, journalists and industry insiders reckon with the era, it is clear that some things have changed. The BBC’s Celebrity: A 21st-Century Story documents paparazzi “upskirting” – the act of taking pictures under another person’s clothing without their consent – which was recently made illegal under the 2019 Voyeurism Act. Meanwhile, reflecting on Noughties media, journalist Sirin Kale emphasised the change in attitudes towards women in an article for The Guardian last week: “The past was a different country. I hope that we never go back.”

As a result, a new trend has emerged, where Noughties tabloid journalists and paparazzi photographers issue public apologies for their behaviour. Last month, infamous celebrity gossip blogger Perez Hilton, who sold T-shirts wishing death on Spears in 2008, apologised on Good Morning Britain. Hilton said: “I regret a lot or most of what I said about Britney, as I’m sure Piers [Morgan, former editor of the News of the World and now ex-presenter on Good Morning Britain] would if he were here.”

Similarly, Stark says: “I talked to several journalists who didn’t make it into the documentary who did feel remorseful, who said ‘I wish I wasn’t so callous in the way that I framed her,’ or ‘I wish I wasn’t trying to crack mean-spirited jokes here just to get praise on my writing.’”

But former Big Brother 7 contestant Aisleyne Horgan-Wallace (who made the front pages after feuding with fellow housemate Nikki Grahame) says that mere apologies do little to reverse the damage done to people who are, for the most part, still alive today.

“I couldn’t believe how some publications could print completely false stories; guys who I’d only meet once saying I’d slept with them and that I was wild and crazy in bed, people who I had considered friends selling stories about me. I couldn’t comprehend how tabloids could print such stories without checking if they were true or considering what effect it would have on my life.”

“Perez Hilton personally apologised to me,” she adds. “But people will still believe what was written at the time. Even if people like Dan Wootton [former News of the World journalist, and current executive editor of The Sun] and Perez Hilton later say stories were untrue, the damage has been done. That’s how the world works. An apology isn’t enough, it also needs a change in behaviour.”

Horgan-Wallace isn’t convinced that tabloids have changed their ways – particularly in light of the ongoing media circus surrounding Meghan Markle, who on Monday discussed for the first time the role that it played in her mental health crisis. “It seems as if members of the royal family have become their new victims,” she says. “They don’t tend to respond or defend themselves.”

Joshi agrees that discussions around the damaging media practices of the era too often risk drawing a line under problems that are far from resolved. “Sometimes it can all be a bit self-congratulatory. We often discuss how the press treated women in the early 2000s, even though it’s not that far removed from how they’re treated now – just the way it manifests is different.” She points in particular to the treatment of trans women in British broadsheets and tabloids, and also the reality TV stars of today. As Kale wrote: “The sickness of the 2000s hasn’t dissipated entirely but it has mutated.”

And of course, the media practices that did change didn’t do so because we all collectively woke up one day and decided they were bad. Matthew Suarez, a former LA paparazzi photographer and author of Paparazzi Daze, tells me that the reason for the fall of the paparazzi industry was, quite simply, the rise of social media. “I remember once when Jessica Simpson ruined an exclusive set of photos I took… My boss had called me to tell me they already had a couple of sales and it was going to be $30,000 or more. Three hours later, Jessica Simpson tweeted a selfie. Magazines cancelled the buy and went for the free picture posted on Twitter.” As Suarez describes, the shift away from paparazzi photography was largely about profit – a force that still governs much of the journalism we read in 2021.

Many of the journalists who profited the most from this culture continue to work today. They include powerful men like Morgan and Hilton, who have climbed the ladder and made millions as a direct result of exploiting primarily young women and girls like Lindsay Lohan, Paris Hilton, Jade Goody, Kerry Katona, Katie Price and dozens of others. Meanwhile, nearly all of the biggest Noughties tabloid stars have suffered intensely with mental health problems and addiction, and struggled into their thirties. In this light, it feels patently clear: the conversation around Noughties media isn’t just one about the decades gone by. The dominant structures of the era, and their repercussions, are still playing out in real time.

From rose-tinted nostalgia to criticism of the millennial media, it seems as if we’re going to be talking about the Noughties for some time. As both Joshi and Stark point out, pop culture is increasingly being shaped by Noughties kids, who are ready to romanticise and reckon with the media of their childhoods in equal measure. The pandemic has only given us more space to do so. But amid our reflections on the turn of the century, we shouldn’t lose sight of the through lines between the past and the present. As we know by now, hindsight is 20:20.

Read More

People spent years taking photos of Britney Spears. But did they ever actually look?