How the North-South divide began

Ask people where the North begins, and you get the most motley and bizarre of answers.

“The North definitely begins once you’ve left Staffordshire and enter Cheshire on the West Coast Main Line,” proclaimed a Blackheath-based teacher from Manchester before adding that although he was “quintessentially Northern” he had friends in Newcastle who “say I’m from the Midlands”’. Mmm-hmm.

An undergraduate at the Royal Academy of Music, in contrast, suggested Stoke-on-Trent – in Staffordshire – was the point where things start to “feel Northern” before qualifying, confusingly, that the “proper North” of course started at Liverpool.

“The North begins at Hull,” proclaimed a bookseller originally from – you’ve guessed it, Hull – telling me it was a silly question in any case because “being Northern isn’t just about geographical boundaries.”

“Nottingham” was the choice of a retired engineer from Lancashire, which puts him at stark odds with a cultural curator from, yes, Nottingham who said “I’m from the Midlands so we don’t identify as Northern – although I think we probably wish we did” pinpointing Sheffield and South Yorkshire as the rightful threshold.

Other answers were more recherché by far: Bicester Village, and, even more absurd, and an answer you get a lot from Londoners: Watford in Hertfordshire, which is particularly insulting because it’s on the Metropolitan Line of the London Underground.

This last is a corruption of the Watford Gap in Northamptonshire, a crossing in the limestone ridge that intersects England diagonally just north of the village (not town) of Watford. The motorway service station that sprouted here in 1959, on the same day the M1 opened, has, in popular culture, often been seen as the gateway between North and South. Unless you believe the Midlands don’t exist, this is highly fanciful as it would place Leicester and Norwich in the North, and Stratford-on-Avon very nearly.

But it makes some sense culturally and metaphorically. It was here, in the 60s that the Beatles stopped off for a plate of grease en route from Liverpool to go to gigs in the South – many other rock stars too. Gritty, but with an aura of rock-star swagger: no wonder this became the southerner’s metonym for the North.

The birth of The North

It is sometimes said that the efflorescence of great industrial cities like Manchester, Liverpool, Leeds and Sheffield in the 18th and 19th centuries marks the North’s historic boundary. But its roots stretch back much further. The idea of “The North” as a distinct political entity probably derives from the 3rd century AD, when the Roman province of Britannia was divided into Britannia Superior, governed from Londinium, and Britannia Inferior, governed from Eboracum (York).

Britannia Inferior comprised of most of what we call the Midlands and North today, up to Hadrian’s Wall – ever has the North been defined by its remoteness from a governing metropolis, in this case, Rome. This boundary aligns quite closely with those who believe the North begins at Nottingham today.

Following the disintegration of the Empire and the settlement of England by Germanic tribes, Angle Northumbria – “North” of “Humber” to the River Forth – briefly blazed bright in the 7th century as a brilliant beacon of learning with the Venerable Bede, monasteries brimming with books, and “Kings of the North” like Edwin (616-633), whom other Anglo-Saxon kings sometimes recognised as overlords, demonstrating how the North, with its stronghold at York, could be the dominant political force in these isles.

But, at the end of the 7th century, the “sea-pirates” from Scandinavia erupted into England at first to plunder but then to populate, and plough. The “Great Heathen Army” wintered in East Anglia in 865 and thereafter kingdom after kingdom fell, like bloody dominoes. Much of Northumbria was overrun, and Mercia too. By 880, the Viking settlers controlled virtually all of England and it fell to Alfred of Wessex, frantically translating books by his hearthplace in Winchester as the dark tides of Viking invasion rolled across the land, to unite the remaining English kings and rout the pagan settlers in London in 886.

As a result, Guthrum, the Viking leader, agreed to convert to Christianity and retreat within agreed borders with a distinctive legal system – the Danelaw – north-east of a line from the Thames Estuary to the Mersey. It’s true that there was inter-marriage and cultural cross-pollination – trial by jury, for example, comes from the Danelaw. But for many decades the Norse and Danish settlers were the tormentors of the Anglo-Saxons to the south, and it may not be too outlandish to suggest a sort of historically-ingrained suspicion dates from that time.

The downfall of The North

The Danelaw eventually became incorporated into the unitary kingdom of England. But those living north of the Humber and Merseyside would prove defiant in the face of Southern control. Perhaps the most vivid episode in a general drama of truculence was William’s Harrying of the North, to enforce his authority, which the Northumbrian and Danish aristocracy were resisting.

In the cruel winter of 1069-1070, towns, villages and farms were ravaged across Yorkshire, Lancashire and Durham. Tens of thousands of Northerners, perhaps, perished; when the Domesday Book was compiled in 1086, much of Northern England had become a wasteland, and the historical memory was invoked when the region fell into decline following deindustrialisation in the mid-20th century.

Further rebellions followed – the Pilgrimage of Grace and Rising of the Northern Earls against the authority of the Council of the North, inaugurated by Richard III, and presiding from York. Its autonomy, eventually, broadly aligned with the three administrative mega-units that officially comprise The North today: the North West, the North East and Yorkshire and the Humber.

A “feeling” of northern-ness

These historical boundaries, as well as the natural features of the landscape, may inform our sense of what The North can be said to be, geographically: the seven historic counties of Cumberland, Northumberland, Westmorland, Durham, Lancashire, Yorkshire and – most controversially – Cheshire. Thus The North might be approximately bounded by three rivers: the Humber, Trent and Mersey.

Yet this only gets us so far. As everyone points out, The North is as much a mindset as a place. As Morrissey puts it, “when you’re northern, you’re northern for ever, and you’re instilled with a certain feel for life that you can’t get rid of.” But what does this mean?

When I travelled around the North earlier this year on a book tour, I found nothing but warmth and conviviality, beauty and Saturnalia, and a fair bit of sun, at practically every turn – in Manchester’s northern quarter with its fizzy red wines and graceful canal-walks, in the chasmic piazza of Darlington with karaoke spilling into the air, in the hills and bookshops of Glossop and Ilkley and the quais and beaches of Liverpool and its satellites; in Newcastle, York, Leeds and Sheffield. In Manchester, someone told me I was the most Southern person he had ever met (though this didn’t stop him coming to visit me in London.)

For the problem – or beauty – of these playful stereotypes is that they can boomerang back into the eye of the beholder: what can seem like a badge of shame, worn right, can be a mark of pride. Thus whereas a Southerner might accuse a Northerner of being curt and lacking in social graces, a Northerner might rejoin that in fact they are merely straight-talking and that this only goes to show the evasive and obsequious nature of their accuser.

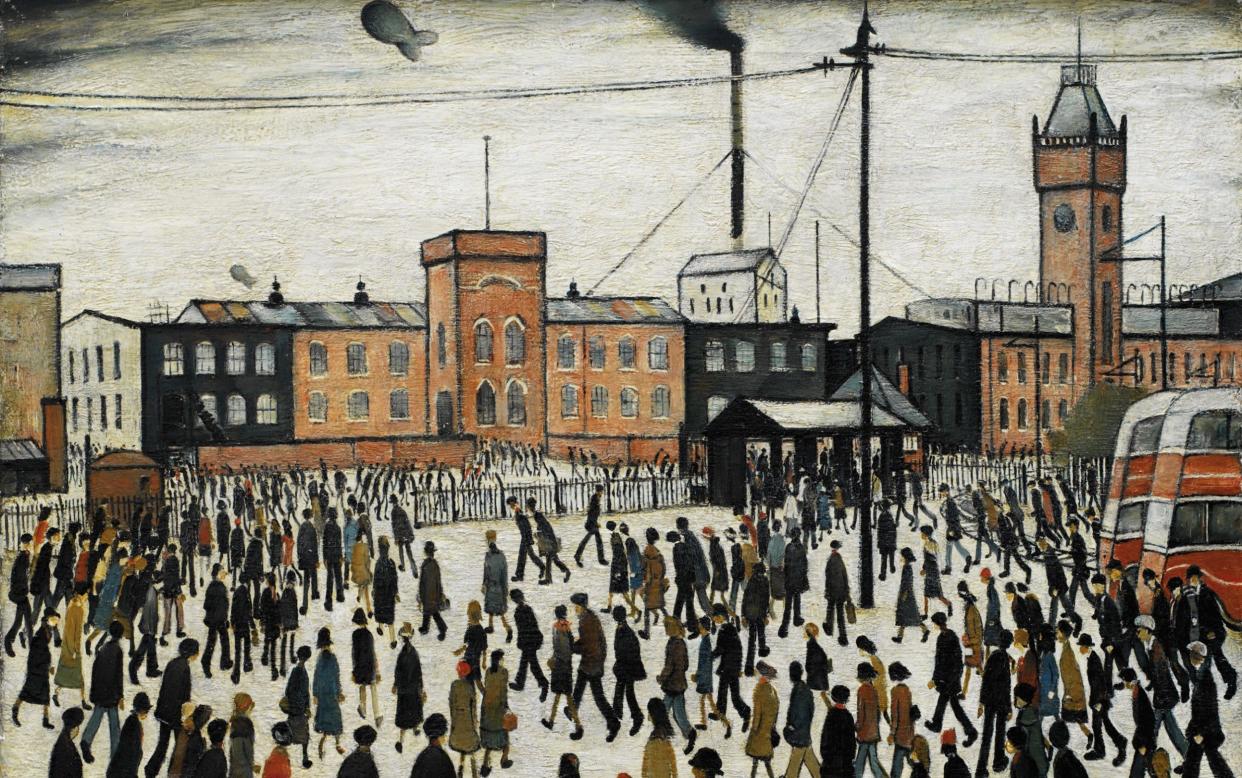

Where a Southerner might lump all Northerners together as working-class, well they might counter that in fact they are meritocratic and egalitarian, far superior to being aloof and racked by class snobbery. And where Southerners might perceive a parochial narrow-mindedness, Northerners see only “citizens of nowhere”. This symbiosis of animus feeds into the landscape, too. The North might, with some justification, be regarded as a vast industrial zone but at least it wasn’t a parasitical “Great Wen” that fed off The North’s graft.

Outsiders might see the North as either oppressively urban or, with its peaks, lakes, and murderous moors, as wildly rural? It’s hard to pinpoint the attributes of Northerness when so much is a matter of perspective.

An identity, rooted in accent

In the end, I suspect, much of it comes down to accent. Although Northern accents are highly prized as an expression of local identity, to outsiders they are all too often seen as comic.

“I heard not a better ale-house tale told this seven years” declared an MP on an oration delivered by the Yorkshire-born Speaker of the House in 1547. It can’t be a coincidence that the Watford Gap line also approximates a loose North-South isogloss between long, and short vowels, between “passt/pahst”, “oop/up” and “bath/baath”.

Reading aloud Keats’s Ode to a Nightingale at school in the early 1950s, the future poet Tony Harison recalls how when he recited the line “Mi ‘art aches” his teacher cut him off: “That’s enough,” he said: “you barbarian.” Perhaps there is truth to the adage that language ‘communicates and excommunicates’.

Other countries have their North-South divides. In Italy, the poor south is frequently contrasted against the richer north. But it is more pronounced in Britain, in part because of the sheer size of London — 15 times more populous than its nearest Northern rival, Liverpool – and with an exceptionally unusual concentration of the turbines of wealth, seat of power and headquarter of the arts and professions all in the same place; “a mart”, as the Northumbrian Bede put it in the 8th century, “of people and goods from all over the world.” Whether “that London” helps to vitalise or vitiate the North is a moot point but all the Northerners I spoke to found it welcoming.

“That’s the great thing about London, it adopts you,” my Hull-born bookseller friend told me, “so I don’t see myself as a southerner or a northerner necessarily, but I do, I think, as a Londoner.” Presumably Dr Johson felt the same way, and perhaps the North and South are not as antithetical as first thought.