Don’t want sex at the same time as your partner? Try this technique instead

Editor’s Note: Ian Kerner is a licensed marriage and family therapist, writer, and contributor on the topic of relationships for CNN. His most recent book is a guide for couples, “So Tell Me About the Last Time You Had Sex.”

Sex equals intercourse. If you’re not having sex like porn stars, you’re not having good sex. Scheduled sex is unnatural.

We live in a society in which we are barraged with those sex myths.

One of the most pernicious myths is that sexual desire is “an electric spark of wanting” that happens naturally and instantaneously. If you don’t experience desire like a bolt of lightning below the waist, there is something’s wrong with you.

In her first book, “Come As You Are: The Surprising New Science That Will Transform Your Sex Life,” sex educator Dr. Emily Nagoski waged a battle against this concept of spontaneous desire, especially on behalf of women who felt they were broken if they didn’t experience desire that way.

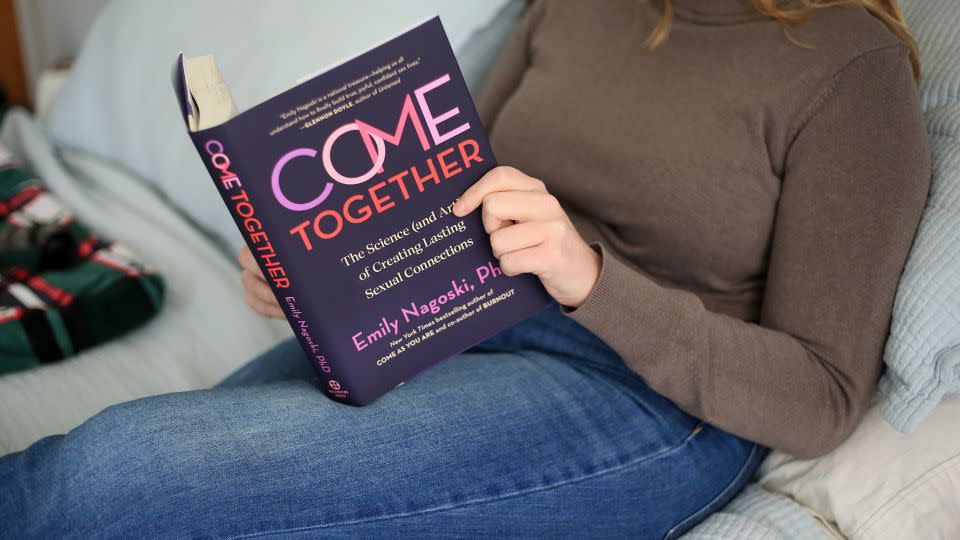

But what happens in long-term relationships when two partners have a different path to desire and can’t get there at the same time or in the same way? To answer these questions, Nagoski has written a new book called “Come Together: The Science (and Art!) of Creating Lasting Sexual Connections” that focuses on maintaining sexual compatibility in long-term relationships.

I talked with Nagoski recently to learn more.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Ian Kerner: In “Come As You Are,” you highlighted the difference between spontaneous desire and responsive desire. Can you explain that concept?

Dr. Emily Nagoski: Unlike spontaneous desire — this idea that we experience desire for sex out of the blue — the concept of responsive desire puts pleasure first. It means that your desire for sex emerges in response to pleasure. When you’re experiencing responsive desire, your body goes, “Oh, right. Yes, this. Hooray!”

Around the time I was writing my first book, pharmaceutical companies were developing drugs for women who didn’t experience spontaneous desire — “pink Viagra,” essentially. But it was clear to me that what they were treating was not a problem. They were treating the fact that people believed a cultural lie. And that’s what I wrote about: Basically, responsive desire is not a disease. There’s no such thing as normal when it comes to sex, and there’s more than one way of experiencing sexual desire.

Kerner: Let’s talk about your impetus to write “Come As You Are.” You get pretty honest about your own sex life.

Nagoski: Ironically, when I write a book, it is very bad for my sex life. Even though I’m reading and writing and thinking and talking about sex all the time, I end up with no interest in actually having sex. After I finished writing “Come As You Are,” things got a little better in my sex life with my husband, but then I went on a book tour, and they got a lot worse. I tried to follow my own advice, which was to put your body in bed and let your skin touch your partner’s skin, so you create context that lets your body access pleasure. And your body goes, “Yeah, that was a great idea.”

But when I did this, I literally just burst into tears and fell asleep instead. And I thought that I needed better advice than I gave in my own book. So I started looking at the peer-reviewed research to see how successful couples sustain a strong sexual connection.

Kerner: Desire discrepancy is the No. 1 sexual issue that couples in long-term relationships seem to grapple with: low desire, no desire, mismatched libidos, a feeling of sexual incompatibility. In “Come Together,” you ask us to see the issue differently. Rather than focusing on desire, you write that “pleasure is the measure,” and that the goal should be centering pleasure.

Nagoski: I was already moving in this direction in “Come As You Are,” and when I looked at the research in this area, the clearer it became that optimal sexual experiences are truly not about desire. When you talk to people who have great sex lives, they don’t talk about desire. It is just not part of the equation. Instead, they talk about pleasure; they talk about authenticity and vulnerability. And above all, they talk about empathy.

Personally, I was interested in having sex, but I could not get to a place where my body was ready for it because I was not in the right mental state. I knew that if I could just get there, my husband and I would have great, joyful, pleasurable, connected, engaging, wonderful sex. But there’s such a strong relationship between stress and struggling with accessing sexual pleasure. That’s what the challenge was for me.

Kerner: We often may not have an innate sense of desire for sex, but to get to pleasure we still need to have willingness and motivation, right? We still need to overcome all those everyday stressors that smother sex. This is where you talk about the concept of the “emotional floor plan,” which is essentially just a model of various emotional “spaces” and how they interact — or don’t — with your “lust” or “sexy space.”

Nagoski: For me, there’s no direct path from my stress space to my sexy space. I have to move through another space in the floor plan first. If I’m in a curious, intellectually engaged, exploratory, adventurous or playful state of mind, it’s easy for me to get into a lust state of mind. I need to make the transition from stress to play and then to lust.

Obviously, everyone’s emotional floor plan is different. Some people can get right from feeling stressed to feeling sexy, for example. Others need to move through feeling cared for before they can get to lust. But the key is to identify which spaces you’re usually in before you feel sexy, and then to do things that get you to a state of mind where you’re open to feeling pleasure.

Kerner: You talk about couples needing a “third thing” in their relationships. What does that mean?

Nagoski: This is a concept I derived from an essay by the poet Donald Hall. He wrote of his relationship with his wife that, “We did not spend our days gazing into each other’s eyes … most of the time our gazes met and entwined as they looked at a third thing.” That third thing can be anything that you’re both excited about or share interest in — your kids, your pets, your favorite sport or musician or TV show. And when you make your sex life a third thing, it becomes a shared point of fascination that you want to work on together.

Kerner: So many of us grew up in homes that were either sex-avoidant — it’s like sex didn’t even exist — or sex-negative — an environment of reproach and shame. So how do we foster “sex positivity” in our own relationships?

Nagoski: For me, being sex positive means having basic bodily autonomy: Everyone gets to choose how and when they are touched and how they feel about their body. That’s freedom — and when we feel free, that’s when we can access pleasure.

Sign up for CNN’s Adulthood, But Better newsletter series. Our seven-part guide has tips to help you make more informed decisions around personal finance, career, wellness and personal connections.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com