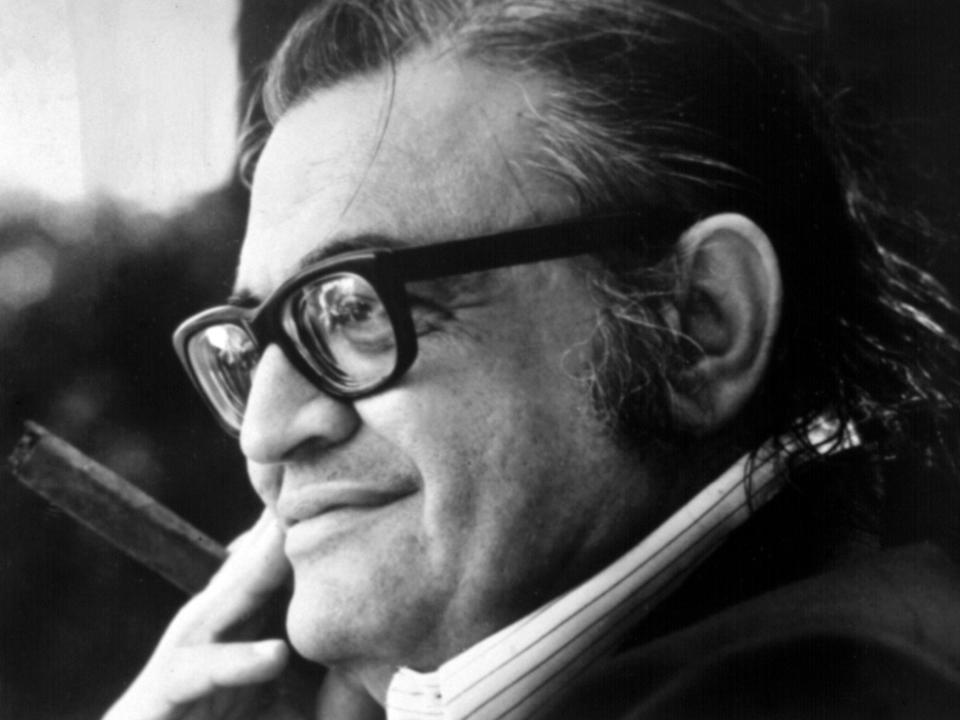

Mario Puzo at 100: The Godfather author never met a real gangster, but his mafia melodrama remains timeless

Mario Puzo’s 1969 novel The Godfather was on the bestseller list for 67 weeks, selling more than 21 million copies worldwide. Puzo’s screenplay for the 1972 film adaptation, arguably the defining portrait of the Mafia in the 20th century, contained some of cinema’s most memorable lines – “I’m gonna make him an offer he can’t refuse” among them – and introduced the Italian words consigliere, capo and omerta into the popular vocabulary.

In 1996, the author told interviewer Charlie Rose about being approached soon after the movie’s release by two “ominous” figures – one of them was John Roselli, a Chicago mob assassin whose corpse was later found floating in Biscayne Bay, inside a chain-locked 55-gallon barrel – who insisted that Puzo must have “had access to the top guys” to pen such an accurate depiction of organised crime. “I’m ashamed to admit that I wrote The Godfather entirely from research,” Puzo wrote in The Godfather Papers and Other Confessions. “I never met a real honest-to-god gangster. I knew the gambling world pretty good, but that’s all.”

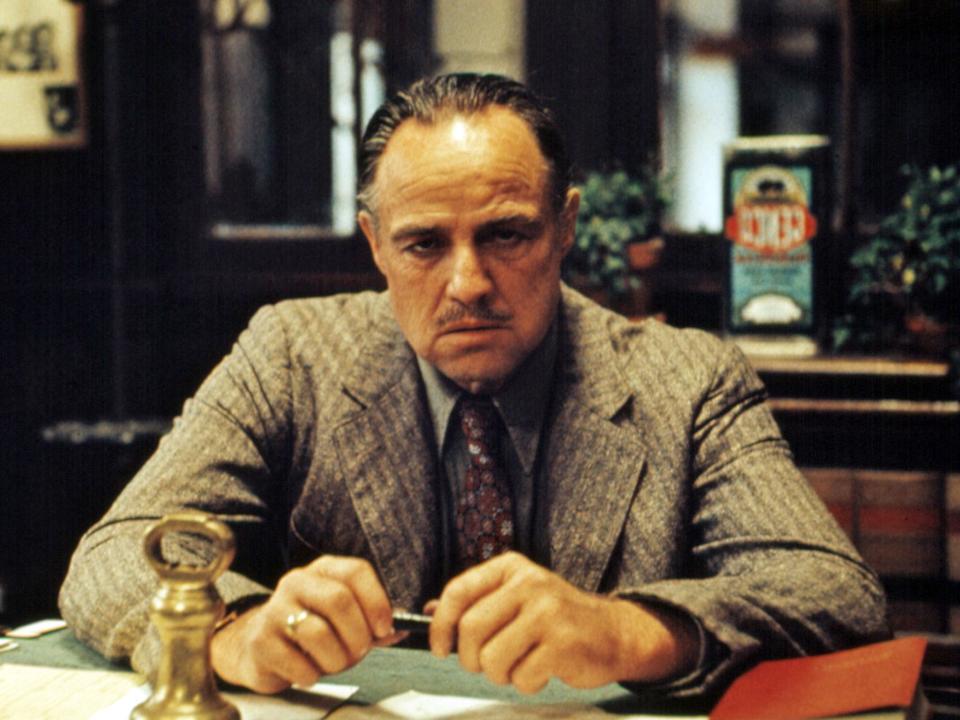

The character of the all-powerful Don Vito Corleone – portrayed first by Marlon Brando and later as a young man in The Godfather Part II by Robert De Niro – was actually modelled on Puzo’s Naples-born mother, Maria. Whenever Brando spoke his lines, the writer said that he “could still hear the voice of my mother”.

Puzo was once asked to compare Vito with his mother. “Like the Don, she could be extremely warm and extremely ruthless,” was his revealing answer to The New York Times. “My father was committed to an insane asylum and when he could have returned home, my mother made the decision not to let him out. He would have been a burden on the family. That’s a Mafia decision.”

Puzo was born 100 years ago, on 15 October 1920, in the west Manhattan area known as “Hell’s Kitchen”. His illiterate father Antonio, a track layer for the New York Central Railroad, left his family when Puzo was 12 and did not return after his confinement for schizophrenia. Puzo’s account of his poverty-stricken childhood is chilling. “‘Stay at home,’ my mother always said, ‘only bad things happen to you outside,’” he recalled.

But bad things happened inside that tiny “slum”. In his memoir, Puzo said that his elder sister Evelyn was the family enforcer. “My brother would bring home a bad report card. She’d bounce a milk bottle on his head and we’d have to take him in for stitches. She scared me so much that when I was in the eighth grade and got a bad report card, I changed the marks. I realised the teacher would notice, so I stayed after school and set a fire to burn up her desk and the report card. They had to evacuate the building. It was a big fire.”

Puzo’s upbringing inspired much of The Godfather, including the scene in which Vito disposes of a gun on a roof. “This guy threw his guns over the airway and my mother took them and held them for him. Then he came and got back his guns. And he said, ‘Would you like a rug?’ So she sent my brother to get the rug, and my brother didn’t realise the guy was stealing the rug until he took out the gun when the cop came. That’s almost entirely in the book and in the movie.”

Puzo’s escape from grim reality was the 11th Avenue public library, where he enjoyed reading about King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. Although he was doing well at Commerce High School, the need for money meant he was forced to leave at 15 to work as a switchboard attendant for the railways. He was once so engrossed in a Dostoyevsky novel that he forgot to change the signals, bringing all the local trains to a standstill.

“I really thought I would spend the rest of my life as a railroad clerk,” said Puzo, who signed up to fight in the Second World War. He served with the Fourth Armoured Division and even though he joked about his war record – describing himself as “a wimp” and an “inept” soldier – he earned battlefield stars after coming under fire in France.

After the war, having married 24-year-old German Erika Broske, Puzo took advantage of the provisions of the GI Bill to fund tuition at the New School for Social Research and Columbia University. His education gave him the confidence to earn a living as a writer. He began by penning pulp stories for men’s magazines – sometimes using the name Mario Cleri – before releasing his first novel, 1955’s The Dark Arena, which was set in occupied Germany.

It took another 10 years to get his next novel published. Although The Fortunate Pilgrim, an autobiographical story about the Italian immigrant experience, was praised by The New York Times as “a small classic”, it sold only 4,000 copies and left him struggling to support his wife and five children. His literary ambitions were mocked by his siblings, who described him as the family “chooch”, an Italian insult meaning “jackass”.

“I was going downhill fast… I was 45 and tired of being an artist,” Puzo wrote in his memoir. “Besides, I owed $20,000 to relatives, finance companies, banks and assorted bookmakers and shylocks. It was really time to grow up and sell out, as Lenny Bruce once advised.” After completing a children’s novel called The Runaway Summer of Davie Shaw, Puzo took the advice of an editor to write about the world of the Mafia.

Puzo retreated to a small basement room in his New York house and started hammering out plotlines on a 1965 Olympia typewriter, occasionally admonishing his children about noise. “He’d shout, ‘Keep it down, I’m writing a bestseller,’” Puzo’s son Tony later told The New York Post, admitting they laughed at their father’s boasts. Puzo’s confidence masked insecurities, though, and he later admitted to Rose that if The Godfather had not been a success, “I don’t think I would have written another book”.

Puzo showed a 10-page outline for his novel about the Corleone crime family to Atheneum, who turned it down instantly. Puzo said that eight publishers in all rejected The Godfather. Undeterred, he took his proposal to GP Putnam and Sons. “The editors just sat around for an hour listening to my Mafia tales and said ‘go ahead’,” Puzo recalled. On the spot, Bill Targ handed Puzo a $5,000 advance. Within days, Targ told Puzo he had sold the paperback rights to Signet for $400,000, an unheard-of figure at the time. A disbelieving Puzo asked Targ if this was “some kind of Madison Avenue put-on”.

Although Puzo was self-critical about the book’s lack of artistic merit – “The Godfather is not as good as the preceding two novels, I wrote it to make money” – it was a sensational hit from the moment it appeared in bookstores on 10 March 1969. Puzo thought some of the popularity of his book was down to a “disenchantment with the American justice system”.

Puzo made a big financial blunder at this point. He sold the film rights to Paramount Pictures for a down-payment of $12,500 and a flat fee of $75,000 if the film was made, ignoring his agent’s warning to wait. “I thought I was really hornswoggling Paramount,” he told the New York Times. Instead, he saw no royalties when The Godfather became the highest-grossing movie of all time, and it ended up earning Paramount more than $150m. “Except for the order to kill, power is exercised in Hollywood exactly as it is in the Mafia – except that the old Mafia had more honour,” Puzo complained in 1996.

Paramount hired 32-year-old Francis Ford Coppola to direct the movie and co-write the screenplay. Both men earned Oscars. “After The Godfather, my dad bought a book on how to write screenplays,” Tony Puzo recalled. “On the first page, it said, ‘The best screenplay ever written was The Godfather.’ After he read that, he threw the book away.”

Puzo came up with the film’s famous line about an offer you can’t refuse. “I made it up. It was carefully constructed. I wrote memos on how we could plant that line, because I was sure it would become a famous line, one of those lines that people would always be using,” he told NPR’s Terry Gross in 1996.

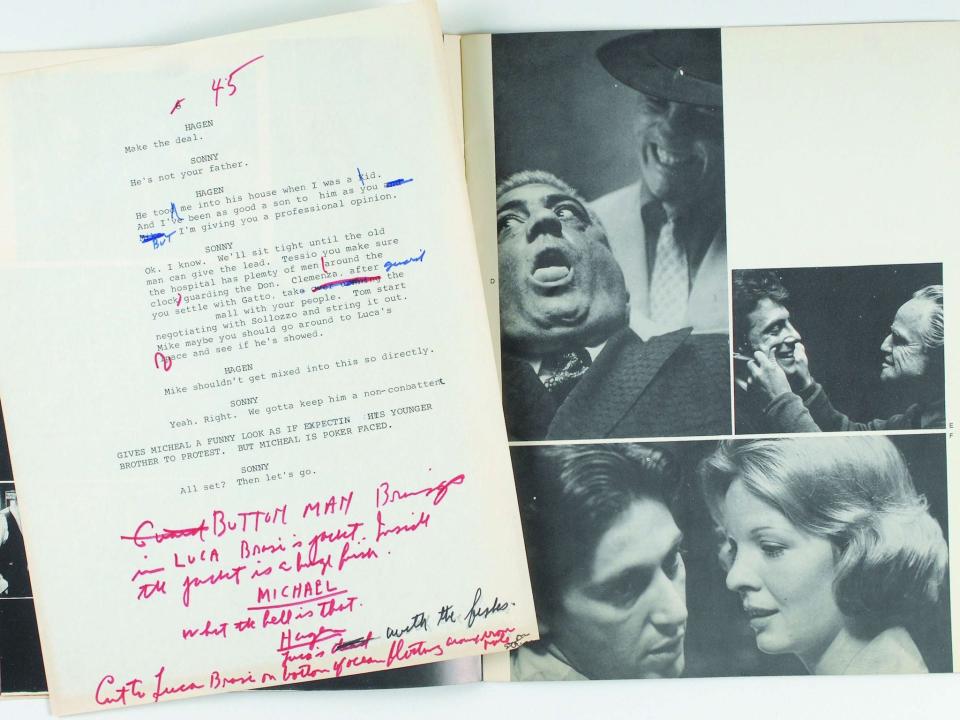

“Mario was always correcting with notes on the page,” Coppola said. “When I wrote the scene of Clemenza describing how to make a tomato sauce, I said, ‘Well, first, you brown some sausage and then you blah, blah, blah.’ And the note from Mario said, ‘Francis, gangsters don’t brown, gangsters fry.’ It’s true, you know, gangsters would never say brown.” The pair also agreed on casting choices. When Coppola was battling Paramount to hire Brando, Puzo wrote to the actor suggesting he “used his muscle” to land the part of Vito.

Their only real dispute came during the making of The Godfather Part II, when they disagreed about the fate of Fredo Corleone (played by John Cazale). “I didn’t want Fredo to be killed in any case, but I said it can’t be done by his brother Michael until their mother had died,” Puzo said.

In 2016, Puzo’s archive was sold by a Boston auctioneer for $625,000. Amid 45 boxes of papers was a screenplay draft for The Godfather, with a fascinating aside about the notorious scene in which Hollywood producer Jack Woltz wakes up to discover the bloodied head of his prized horse in his bed (Coppola used a real head, delivered from the slaughterhouse of a New Jersey dog food factory). In Puzo’s novel, the head was on the bedpost when Woltz woke up. When Puzo saw Coppola’s dramatic change, he penned a note in the margins that read: “Francis: you rascal, very clever.”

The severed head was delivered as a warning to force Woltz to hand a big part in a movie to the fictional mob-backed singer Johnny Fontane (played by Al Martino). In the director’s commentary on the Blu-ray edition of The Godfather, Coppola admitted that “obviously Johnny was inspired by a kind of Frank Sinatra character”. Ol’ Blue Eyes saw red when the film came out; Sinatra launched a furious verbal assault on Puzo when they ran into each other at the celebrated Chasen’s restaurant in Los Angeles.

“Contrary to his reputation, Frank Sinatra did not use foul language,” Puzo recalled in 1972. “The worst thing he called me was a pimp.” Sinatra told Puzo that he would like “to beat the hell” out of him, hissing “choke, go ahead and choke” as the “humiliated” author left the restaurant. In his memoir, Puzo joked that it was a rare case of a northern Italian threatening a southern Italian with physical violence. “This was roughly equivalent to Einstein pulling a knife on Al Capone,” Puzo noted drolly. “It just wasn’t done.”

Puzo faced wider complaints that his characters were a stereotype of Italian criminality. The protests were led by New York’s Sons of Italy organisation. In February 1971, The Godfather producer Albert Ruddy was called to the Park-Sheraton Hotel to discuss the movie with mob boss Joseph Colombo. The head of New York’s Mafiosi took out his reading glasses and stared at the opening sentence of the 155-page script. Finally, he turned to Ruddy and asked, “What does ‘fade in’ mean?” “I knew he’d never get to page two,” Ruddy told the New York Post. Colombo agreed to call off planned disruption of filming after Ruddy agreed to delete the words “Mafia” and “Cosa Nostra” from the script.

The reaction from other mob bosses to the film was glowing. On one of his regular trips to the casinos of Las Vegas, Puzo found that a gambling debt he had run up was marked “paid”. When Puzo protested, he was told, “It’s a certain party’s pleasure.” Salvatore “Sammy the Bull” Gravano, who was a hit man for the Gambino crime syndicate, even gave a newspaper endorsement of the film, saying, “I left The Godfather stunned. I floated out of the theatre. Maybe it was fiction, but for me, that was our life. I remember talking to a multitude of ‘made guys’ who felt exactly the same.”

The success of the first two Godfather films (1974’s Part II, also starring Al Pacino and Diane Keaton, was a $100m success for Paramount) turned Puzo into an in-demand screenwriter – and he made a small fortune co-scripting two Superman movies and The Cotton Club. “Mario was always a gambler, but after his success he gambled for higher stakes,” said Puzo’s lifelong friend Joseph Heller. The author of Catch-22 said he and Puzo used to stay up several nights a week playing cards, and even created their own board game, called Scapegoat. “We redesigned a board game played with a deck of cards. It’s a good gambling game,” Heller told Playboy in 1975. Puzo put his betting knowledge to good use in 1978 when he wrote Fools Die, a novel set in Las Vegas. He sold the paperback rights for $2.5m.

When Puzo and Coppola reunited in the late 1980s to write the script for The Godfather Part III, they worked at a Reno gambling hotel. That final instalment, which was nominated for seven Oscars, is being released in a newly restored version in cinemas this December, with a new beginning and ending, under the title Mario Puzo’s The Godfather, Coda: The Death of Michael Corleone.

As well as gambling, Puzo spent some of his riches on renovating a house in Bay Shore, Long Island. Although overweight and an excessive eater – he loved Chinese food and fine Italian cuisine – he was a talented tennis player and had a court built in his large garden. For the final 21 years of his life, he lived with Carol Gino, a registered nurse who cared for his wife Erika through the breast cancer that killed the 59-year-old in 1978.

Puzo remained “addicted” to reading, sometimes for 16 hours a day, and often had 20 books on the go consecutively. Among his favourite novelists were John Le Carre, Larry McMurty and “English lady novelists” Faye Weldon and Muriel Spark (who was actually born in Edinburgh).

In 1992, Puzo published The Fourth K, a futuristic thriller about the Kennedy family. This was followed by 1996’s The Last Don, a return to Mafia-based fiction, which was turned into a television mini-series starring Daryl Hannah and KD Lang. The CBS show also featured Vincent Pastore, a man who went on to play Salvatore “Big Pussy” Bonpensiero in The Sopranos, a series that owed so much to The Godfather. Creator David Chase was a student at Stanford when Puzo’s novel came out. “I was just ready for that book,” Chase said in 2002.

Puzo was a heavy cigar smoker for years, something that helped bring on chronic diabetes and the 1995 heart attack that made walking difficult and forced him to install an elevator in his house. Puzo was 78 when he died of heart failure on 2 July 1999. He had just finished his final novel, Omerta.

One project that went unfulfilled was the movie The Godfather Part IV. Puzo wrote “half a script” telling the story of Sonny Corleone (brilliantly played by James Caan), but it was stymied because Paramount owned the rights. “I only wish I had Hollywood power to get that picture made,” Puzo lamented.

Shortly before he died, Puzo insisted that The Godfather movie was better than his novel. “The first Godfather is in the best 20 movies of all time – I don’t think you could say that about the book,” he remarked. “I wrote below my gifts in The Godfather… I wished like hell I’d written it better.”

Yet his timeless tale is so much more than a gangster melodrama; it is a remarkable dissection of the immigrant experience and a biting commentary on greed. And his best lines – such as “Never hate your enemies, it affects your judgment”, or the poetic “Luca Brasi sleeps with the fishes” – remain classics, part of why Puzo deserves to be celebrated as one of the 20th century’s most gifted storytellers.

Read more

Why Goodfellas is still the greatest gangster movie ever made

Martin Scorsese: ‘At this vantage point of age, you have to let go’