Love on the Ground: the intimate illusions of Jacques Rivette’s chateau mystery

An orchestra warms up and an audience gathers in the opening scene of Love on the Ground. But in Jacques Rivette’s 1984 film we can’t always trust what we see and hear. The music is quickly over – there will be little more over the next three hours – and these theatregoers are not in a grand auditorium but are led, straight from the street, into an apartment for a piece of promenade theatre. Shuttled from room to room, they watch a farce complete with pyjama-clad philanderer, his hidden lover, her conspicuous pair of high heels and copious amounts of door-slamming.

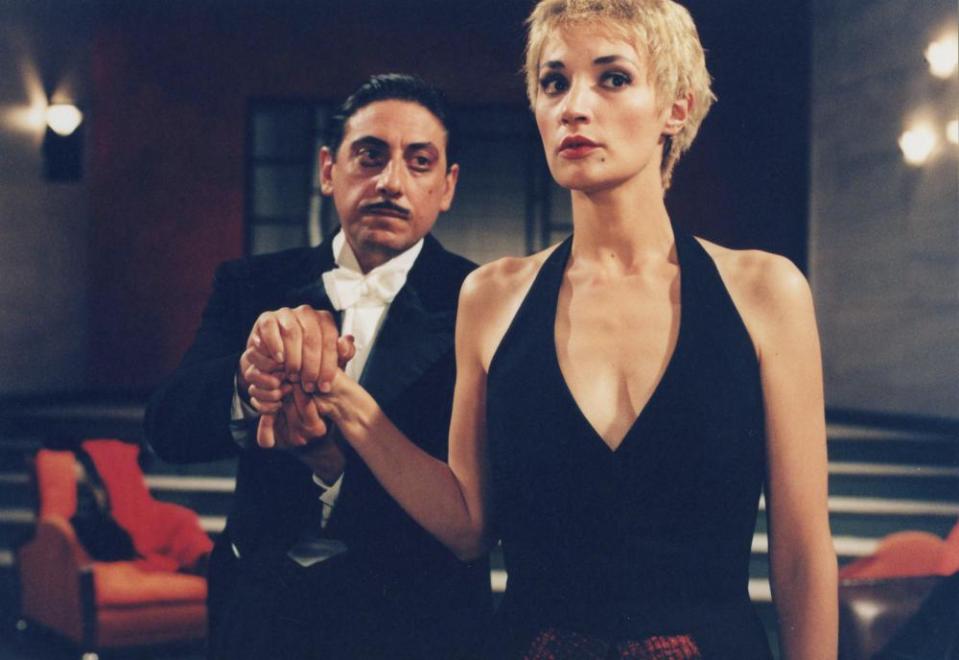

The uncredited author of this farce, Clémont Roquemaure, happens to be in the audience and when he visits the performers after the show, they fear a lawsuit. But the preening Roquemaure (played by Jean-Pierre Kalfon) cordially invites the actors to his chateau. The next day, Emily (Jane Birkin) and Charlotte (Geraldine Chaplin) are surprised to be offered roles in his next drama. This is the deal: move into his house, rehearse for a week, and give a one-off performance to a private audience.

Rivette wraps a mystery around this theatre production, just as he does around the other films about the stage that he made over his long career. In Va Savoir (Who Knows?, 2001), Jeanne Balibar and Sergio Castellitto play a couple staging a Pirandello play in Paris to less than packed audiences; she meets an old flame while he falls for a young woman who helps him solve a puzzle about a long-lost text by Carlo Goldoni. La Bande des Quatre (Gang of Four, 1989) is about a group of actors in a houseshare; the film is split between lengthy rehearsal scenes for their revival of Pierre de Marivaux’s Double Inconstancy and their life in the Parisian suburbs, as their home is infiltrated by a man who may be in the arms trade, an art thief or a police officer. In Rivette’s debut feature, Paris Nous Appartient (Paris Belongs to Us, 1961), conspiracy theories about a series of murders spread amid rehearsals for a production of Shakespeare’s Pericles.

It is Hamlet that haunts Love on the Ground (L’Amour par Terre). As rehearsals proceed, it transpires that Roquemaure’s play is heavily autobiographical and concerns a love triangle including the magician Paul (played with characteristically uncanny humour by André Dussollier) and the enigmatic Béatrice, who has disappeared. Why has Roquemaure written the play, what is his reason for staging it and how come he’s concealing the ending from the actors? Is he, like Shakespeare’s prince in Hamlet’s play within the play, looking to catch the conscience of an audience member?

If Roquemaure’s play is a trick, well, the film has plenty of others. When Paul first meets Emily he practises the oldest trick in the book, producing a dove out of thin air. But Paul insists it is the playwright who is a conjuror, not he, and the chateau’s inhabitants are repeatedly blindsided by illusions of alternative versions of themselves as if in trick mirrors. The grand house has elaborate bedrooms and when the two women stumble across Béatrice’s room they try on her outfits as if getting into character to understand her motives for leaving. As you’ve probably guessed, there’s plenty of bed-hopping in this chateau but it’s never of the farce variety. The film retains a naturalistic style with Rivette’s usual measured pace; it gently unsettles rather than functioning as a thriller or a horror film.

What of the play within the play? In some films about theatre they have little to do with the off stage plot; in others they work as a mirror to it. But in Love on the Ground the autobiographical scenes being rehearsed function as a series of flashbacks, albeit subjective, that may explain what happened to the missing woman. The playwright is presented as all-powerful: he will direct and produce the one-off performance. He owns the chateau just as he owns the story; the others are merely players, whether that be the actors in rehearsals or the guests he invites to the unveiling of the drama. Charlotte believes that Roquemaure will reveal his true self in the play and that it will lead her to grow closer to him, but the potential for obscurity is also apparent. When Charlotte comments that the dialogue they have been given feels fake, it seems like more than an actor’s feedback but a direct accusation that the playwright is concealing the truth.

In the past I’ve struggled with some of Rivette’s long and winding films including Céline and Julie Go Boating (1974), which shares the themes of doubling, magic and a story within a story. But Love on the Ground is as enthralling as it is perplexing, from that opening scene that taps into the intimate promise of theatre to an ending that even the actors await with uncertainty.

Love on the Ground is available on DVD