A lost piece of the British Caribbean is coming in from the cold

The approach to Providenciales Airport is the sort of descent – fraught with a nagging anxiety which ratchets up by the minute – that might give more nervous fliers palpitations. Why? Because there is absolutely nothing beyond the window, as the plane drops lower and lower, but an all-encompassing, horizon-spanning, oceanic blue.

It all works out, of course. A runway appears, magically, below the wheels, and the aircraft glides to a halt without a hiccup. But long before you touch down, you are aware that the Turks and Caicos are no craggy St Lucia, with twin Pitons probing the sky; no volcanic Nevis pushing its caldera into the clouds. These are flat, coral islands, so low to the Caribbean Sea that you will scarcely spot them before you set foot upon them. Three miles north of the airport, the Blue Hills ridge stands as the archipelago’s highest peak, so to speak, rising to an altitude of 161ft (49m). You will struggle to spot it, as well.

I step down onto the tarmac, into a Providenciales International that, similarly, makes no claim to great scope or stature. You could not mistake it for Barbados’s Grantley Adams Airport, with its near-constant roar of departing engines, and its retired Concorde as a museum piece. The Virgin Atlantic Boeing 787 I have emerged from resembles a condor among chaffinches, towering over the smaller planes and private jets dotted about the airfield. It looks so big, in fact, that I wonder how it has landed here.

The main point, perhaps, is that the plane is here – and that it is a novelty. Sir Richard Branson’s red-liveried airline began flying between London Heathrow and Providenciales last November – and in doing so, launched what is currently the only non-stop air link between Britain and the Turks and Caicos Islands (British Airways also serves Providenciales – but only after a pause in Nassau, in the Bahamas.)

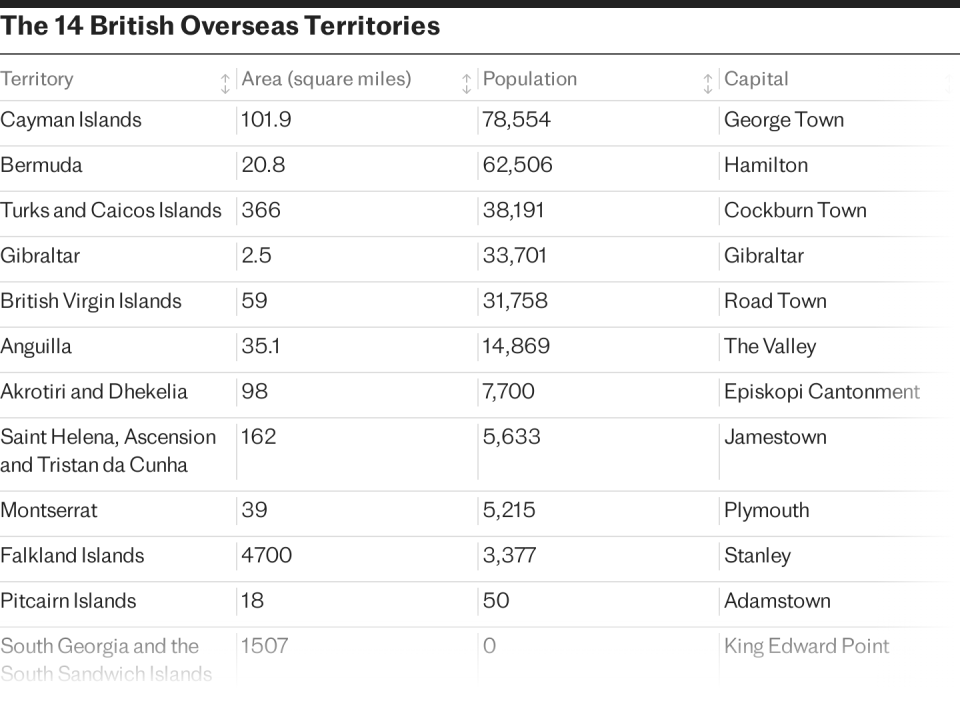

This is mildly surprising news. Because, in spite of its resolutely Caribbean location – north of Haiti and the Dominican Republic, due east of Cuba, a stone’s throw south-east of the Bahamas – the Turks and Caicos archipelago is a British Overseas Territory (BOT). The third largest, in fact, by population (after the Cayman Islands and Bermuda). Moreover, the Union Jack has flown here for a long time – the islands have been tied to the UK since 1783. They have bounced through various administrative frameworks in that period, bundled in with the Bahamas, then Jamaica, at various times. But they have been a separate entity, with their own government, since 1959 – and a BOT since 2002.

In other words, prior to November, a direct flight between London and Providenciales was long overdue – even if the scale of the destination does not demand its own page in the atlas. For what the Turks and Caicos Islands lack in height, they do not compensate for in size. Not to any real extent. Indeed, you have to scan the map carefully for the “Turks” half of the equation – eight pin-prick outcrops on the eastern side of the archipelago – of which the biggest, the optimistically named Grand Turk, amounts to just seven square miles. You could fit it eight times into Middle Caicos, the largest fragment (55.7 square miles) of the more substantial Caicos islands. But then, these things are relative. Providenciales is the most populous piece of the jigsaw, home to some 24,000 of the archipelago’s 44,500 inhabitants. Yet it only adds another 38 square miles to the total.

Still, this is one of those situations where size does not matter. Because as well as being the population hub, Providenciales is the key point of interest for holidaymakers. Tourism is the archipelago’s main income stream, accounting for over one third of GDP (35 per cent) – way ahead of the second most important segment, financial services (13 per cent).

Evidence of this rule of attraction is laid out along the north coast, in a gleaming necklace of luxury resorts – and luxury is definitely the word here. The Turks and Caicos archipelago is not a place for bargain breaks; not so much a convenient three-star fly-and-flop zone as an unabashed five-star playground. In most cases, this catering to the wealthy is discreet – genteel villas and sophisticated beachside properties. In others, it is rather more obtrusive; not least the vast Ritz-Carlton hotel, which rears over the village of Grace Bay.

Three miles to the west, the Wymara Resort sits much closer to the “discreet” end of the market. It spreads out on either side of a pool that all but beckons you in as soon as you arrive, its softly lit shallows and curtained daybeds waiting just beyond the lobby. Rooms and suites (91 in total) are a haze of white, walls and linen cast in the same pale hue. Balconies gaze at a powdery beach, and the warm swell of the sea – that Caribbean blue framed by a line of ragged spray, where waves break ceaselessly on the coral reef that lies half a mile off-shore. A hop away on the south edge of Providenciales – the island is but a sliver where it narrows at the middle – the Wymara Villas complex repeats the trick.

The voices around the swimming pool are, for the most part, American – another clue as to why a direct flight from the UK has only just been added to the timetable. A case of chicken and egg it may be, but for all the longstanding connection to Britain, Britons have simply not been travelling to the Turks and Caicos in any great number. The islands attracted 1.6 million visitors in pre-pandemic 2019; 82 per cent of them hailed from the United States, a further 9 per cent from Canada. Only 4 per cent came from Europe.

The stars and stripes feel close at hand wherever you turn. The Providenciales Airport departures boards are largely devoted to American cities, with Boston, Chicago, Miami, Fort Lauderdale, Philadelphia, Minneapolis, New York, Dallas, Baltimore and Washington DC all present and correct. Restaurant menus – including at Wymara’s flagship Indigo, where chef Andrew Mirosch runs the show – tend to be priced in US dollars. In Grace Bay, the souvenir stores – with their pithy-slogan T-shirts and gaudy gifts – seem more geared to Midwest snowbirds than West Country sun-seekers. And Danny Buoy’s, a sports bar on the main drag of Grace Bay Road, is a clear case in point. The giant cut-outs on its front wall do not concern themselves with Messi, Ronaldo or Harry Kane, but Patrick Mahomes – star quarterback of the Kansas City Chiefs. Its drinks list is spring-break nirvana; a chorus of giddy shots and double-entendre cocktails, at $12 (£9.40) a go.

Virgin Atlantic’s new presence on the island will not spark a sudden shift in this image or this demographic. But then, it does not need to. Real life filters through if you look for it – notably at Da Conch Shack, a popular Providenciales hotspot where the accents at the tables on the sand are as much local as American. So is the food; a filling cornucopia of conch fritters and grouper fillets. And the entertainment, too. As the evening lengthens, a Junkanoo performance breaks out on the beach, its rhythms growing louder as the parade moves along the shore – until the drummers and dancers step into the light and make merry in every available space. Gloriously infectious, the ritual has its roots in the darkness of slavery, taking form in the 18th century on the sugar plantations of the British Caribbean (particularly in Jamaica and the Bahamas). Tonight, it is all brightness and joy.

The scene is considerably quieter, but no less compelling, if you venture to the eastern end of Providenciales, where the land breaks down into calm waters and smaller cays. Among them, Mangrove Cay is a perfect setting for a leisurely morning in a kayak, its raw coral swaddled – as its name would suggest – in swampy foliage. By contrast, the channels around it are pristine and remarkably clear; so much so that you can see the green, leatherback and loggerhead turtles that haunt these waters long before they break the surface – sharp-beaked heads bobbing up, curious, between the plastic prows.

You can go out further and faster from the same departure point, the Blue Haven Marina, on a catamaran tour. In doing so, I gain a fuller appreciation of the size of the Caicos Bank, that coral barrier along the north coast – by some metrics, the third biggest reef system on the planet (after the Great Barrier Reef and the Great Mayan Reef).

The plan, initially, is to aim for Pine Cay, a sparse and (mostly) uninhabited outcrop a little to the north-east – but the moment the vessel tiptoes through a gap into the open ocean, the swells churn and roll in apparent protest, revealing both the strength of the currents and the level of protection provided by the archipelago’s coral guardian. So we retreat, back towards the shelter of Mangrove Cay, for swimming and snorkelling in less demanding waves. The Turks and Caicos Islands look no more like mountains from this exact sea level – but with the sun sparkling, and the sky a flawless blue, nothing could matter less.

Getting there

Virgin Atlantic (0344 874 7747) flies to the Turks and Caicos from London Heathrow twice a week. Return economy fares cost from £616 per person.

Staying there

“Garden Studio” double rooms at Wymara Resort and Villas (001 888 844 5986) cost from US$800 (£631) per night, including breakfast.

Exploring there

Kayak and catamaran tours can be arranged via Luxury Experiences Turks & Caicos and Big Blue Collective (bigbluecollective.com).