Long lost secrets from our past revealed by climate change

Hidden secrets

Josep Lago/Getty

Climate change is having a devastating impact on our planet, destroying natural landscapes with flooding, droughts and other forms of extreme weather. But sometimes, among the devastation, these climatic phenomena can expose artefacts and archaeological sites previously lost to time.

Read on to see the desert cities, thawed objects and centuries-old hunger stones revealed as a result of climate change...

Dolmen de Guadalperal, Spain

Pablo Blazquez Dominguez/Getty Images

The Spanish region of Extremadura is famed for being dry – but when the Iberian peninsula experienced one of its driest Junes on record in 2019, a remarkable historic site that had not been seen for 50 years reared above the waterline. Dubbed the ‘Spanish Stonehenge’, the Dolmen de Guadalperal is a Megalithic stone circle believed to date as far back as 5000 BC. However, the dolmen was drowned by the Valdecanas reservoir in 1963 after the construction of a dam.

Dolmen de Guadalperal, Spain

Pablo Blazquez Dominguez/Getty Images

The dolmen was originally excavated in 1926 by German archaeologist Hugo Obermaier, who noted 140 upright boulders arranged in a concentric circle. Since the creation of the reservoir in 1963, the dolmen has only been seen four times, including in 2022. Once again, it has sunk beneath the surface, but the reservoir endangers its existence; locals have called for the stones to be removed to a drier location, as some granite monoliths show signs of significant water damage.

Submerged forest, Wales, UK

Robin Weaver/Alamy Stock Photo

In 2014, fierce storms stripped a beach in Cardigan Bay, Wales of thousands of tonnes of sand, revealing an eerie sight: an ancient, petrified forest buried beneath the sea. The forest – which radiocarbon dating suggests stopped growing 4,000 years ago – once stretched for a few miles and was filled with an arboreal array, including pine, alder, oak and birch. The existence of the forest was already known to scientists and archaeologists, but the unprecedented storms revealed some curious new finds.

Submerged forest, Wales, UK

The Photolibrary Wales/Alamy Stock Photo

The storms exposed an ancient timber walkway, which Wales’ early inhabitants constructed to cross an increasingly waterlogged terrain as the sea levels rose around them. The trees were eventually buried under layers of peat, preserving human and animal tracks, before being submerged by the sea. The forest’s unfortunate fate gave rise to a Welsh legend of Cantre'r Gwaelod, a mighty kingdom drowned beneath the waves. The frozen-in-time forest can sometimes be seen at extreme low tides in the town of Borth.

Sunken warships, Serbia

Associated Press/Alamy Stock Photo

Summer 2022 was a time of dire droughts, particularly in central Europe, when the Danube reached its lowest level in almost a century. Low water levels revealed some unusual occupants on the river bed; in the Serbian port town of Prahovo, the rusting hulks of 20 Nazi warships lay in the water. They formed part of the Black Sea Fleet, but as Russian forces advanced up the Danube in 1944, the Nazis deliberately scuttled the ships to stop them falling into enemy hands.

Sunken warships, Serbia

Associated Press/Alamy Stock Photo

The ships pose a danger to the people of Prahovo. A Serbian transport minister stated the warships may still be carrying up to 10,000 explosive devices, which have the potential to leak toxic chemicals into the water (not to mention, explode). The hulks, exposed by extremely low water levels, also made navigating the river far more difficult: the width of the shipping lane at Prahovo was almost halved when they were visible. Plans to remove the explosives and break down the warships were made in 2022, but many had still not been extracted when the Danube returned to its normal levels.

Kemune Palace, Iraq

University of Tubingen, eScience Center, and Kurdistan Archaeology Organization

In 2018, the waters of the Mosul Dam reservoir near Kemune in Iraq's Kurdistan province drastically fell away due to drought, revealing a sturdy brick palace built during the period of the Mitanni Empire. The Mitannis thrived in the 15th and 14th centuries BC in the fertile Mesopotamia region and were a notable ally of ancient Egypt, but little is known about their society because the few Mitanni archaeological sites that exist have rarely contained written texts.

Kemune Palace, Iraq

University of Tubingen and Kurdistan Archaeology Organization

The accidental discovery of the palace at Kemune has the potential to greatly enhance our understanding of this ancient kingdom. Besides red-and-blue hued murals in a remarkable state of preservation, 10 clay cuneiform tablets were excavated. They contain writing that dated the palace to around 1800 BC. These texts were recently translated and have revealed new details about the Mitanni economy and society, including that the grand palace was a building for public use.

Iron Age shoe, Norway

@brearkeologi/X

Climate change means glaciers are melting at an alarming rate, but the thawing ice can sometimes defrost centuries-old items previously lost to the permafrost. In 2019, a hiker on Norway’s Lendbreen glacier spotted a tangled mass of old rawhide and lace poking out of the ice. He shared its location with glacial archaeologists from Secrets of the Ice, who rushed to the site before a snowstorm could blanket the mysterious object over again.

Iron Age shoe, Norway

Espen Finstad/secretsoftheice.com

The hide was soon reconstructed into a dapper-looking sandal. Radiocarbon dating dated the object to the 4th century AD. Even more interestingly, Secrets of the Ice archaeologist Lars Pilo said the size nine shoe closely matched the style of Roman carbatina sandals, suggesting that fashions travelled across the entire European continent. The archaeologists have found plenty more treasures within the Lendbreen glacier – it’s now believed to be the site of a mountain pass, used for a thousand years but abandoned over 500 years ago.

Pre-Viking skis, Norway

Andreas Christoffer Nilsson/secretsoftheice.com

The Secrets of the Ice project has also excavated a hoard of other treasures from Norway’s melting glaciers, such as these 1,300-year-old skis. The first Iron Age ski was uncovered in 2014, while the second ski was dug out after further glacial melt in 2021 – in far better condition, as it was buried much deeper under the ice. Archaeologists have theorised that as many objects related to reindeer hunting have been found in the area, the skis may have belonged to a hunter.

Pre-Viking skis, Norway

Espen Finstad/secretsoftheice.com

Measuring about 6.2 feet (1.9m) in length, the skis were tied to the user’s foot using leather straps and birch bark bindings. They had also been repaired in multiple places, showcasing Iron Age ingenuity. They are among the world’s best-preserved Iron Age skis – best of all, as of June 2023, the skis, the sandal and other amazing artefacts found by the Secrets of the Ice team can be seen in a permanent exhibition in Lom, Norway.

Nunalleq artefacts, USA

Mark Ralston/Getty

As glaciers melt with the global temperature rise, so too does the frozen soil in Earth’s arctic regions. In Alaska’s Yukon, archaeologists from the University of Aberdeen have been digging away at newly defrosted dirt to learn more about the old Yup'ik village of Nunalleq – about 400 miles (644km) west of the state’s largest city, Anchorage. As the ice defrosts, it’s a race against time to preserve the valuable Yup'ik artefacts before they degrade.

Nunalleq artefacts, USA

Mark Ralston/Getty

The site has yielded around 100,000 fascinating objects from Yup'ik life. Pictured, lead archaeologist Rick Knecht shows some artefacts to local Yup'ik children. The most interesting find was the charred remains of a communal sod house (a log cabin used during frontier settlement of Canada's Great Plains and the US in the 1800s and early 1900s), which contained the bodies of almost 30 murder victims. Yup'ik tales had long told of a brutal massacre of an entire village some time before 1840, but the site had never been located. Perhaps Nunalleq was where it took place – Dr Knecht described the site as the “Yup'ik equivalent of Troy”.

Nero’s Bridge, Italy

Andreas Solaro/Getty

In 2022, Italy experienced its worst drought in 70 years, bringing water levels in the Tiber down to critical levels. The low water revealed a pier of a Roman bridge that’s rarely seen. Nero’s Bridge – almost directly beneath Rome’s 19th-century Ponte Vittorio Emanuele II – was built in the first century AD. Despite the bridge’s name, historians aren’t sure whether this bridge was actually built by the notorious Nero – the Latin name ‘Pons Neronianus’ (Bridge of Nero) only appeared in chronicles in the 12th century.

Nero’s Bridge, Italy

Stefano Montesi - Corbis/Getty

The bridge fell into disrepair and was partially dismantled by the 3rd century. Then, in the 19th century, two of the bridge’s four pillars were demolished to allow larger river boats to pass. One pier can sometimes be seen in a normal dry season, but it took an exceptional heatwave for this second pier to be visible; a rare opportunity for Rome's modern citizens to peer at an unseen part of their city's history.

Corinthian columns, Israel

@IsraelAntiquitiesAuthority/Facebook

After a strong storm ravaged the coast of Israel in May 2023, sea swimmer Gideon Harris spotted something unusual through his goggles. At the bottom of the seabed lay some hand-carved marble objects, revealed by the shifting sands. Harris contacted the Israel Antiquities Authority, which sent divers to excavate the site. The columns were 1,800 years old, measured up to 19.6 feet (6m) and were made of the finest marble, decorated in a floral Corinthian style. So how did they end up at the bottom of the sea?

Corinthian columns, Israel

@IsraelAntiquitiesAuthority/Facebook

Archaeologists believe the columns were the cargo of a huge Roman ship, intended to adorn a grand public building such as a theatre or temple. During a storm, the heavily-laden ship was wrecked in shallow water, its fine cargo scattered across the sea floor. The find helps solve an age-old academic question about where Roman architectural elements were completed – these columns were being imported in a partially-carved state, leaving local artisans to finish the job, whereas previously it was thought that pieces were completed in their land of origin, then shipped to their destination.

C-53 plane, Switzerland

Ursula Perreten/Shutterstock

Switzerland’s 2018 heatwave caused large parts of the Gauli glacier (pictured) to melt away. As the glacier retreated, the wreckage of a C-53 Skytrooper plane that had crashed there in 1946 was revealed – entombed inside the ice for 72 years. The transport plane was travelling from Austria to Italy, carrying four crew and eight passengers (including two high-ranking US military officers). However, bad weather and sudden winds disoriented the pilot, leading the plane to crash-land on the glacier at an altitude of almost 11,000 feet (3,350m).

C-53 plane, Switzerland

Edvard Majakari/Wikimedia Commons

All people aboard the plane survived and were rescued in a huge Swiss rescue operation a few days later, with reports suggesting they’d had to drink snow water and ration chocolate bars to survive. The C-53 plane (similar to the one in this image) was soon buried under layers of snow and ice, but the hot and dry summer of 2018 meant scientists were able to recover much of the wreckage. Tourists came to see the stricken plane once it was found; the final chapter of a decades-old saga.

Brookhill Ferry, Louisiana, USA

Associated Press/Alamy Stock Photo

On his daily walk trawling the Mississippi riverbanks for artefacts, archaeology enthusiast and Baton Rouge resident Patrick Ford saw an otherworldly wooden exoskeleton poking out of mud. He hit the jackpot that day – extreme drought meant that a 19th-century ferry was exposed, in full, for the very first time.

Brookhill Ferry, Louisiana, USA

Associated Press/Alamy Stock Photo

State archaeologists soon confirmed that it was the wreck of the Brookhill, an 1896-built ferry that crossed between Baton Rouge and Port Allen (on the other side of the Mississippi) each night. The ship sank in a storm in 1915, never to be recovered – until 2022, when 80% of the hull was suddenly above the surface. The wreck was briefly opened to the public, but closed once the Mississippi returned to its usual levels. You can still see a 3D model of the wreck on the state’s website.

Luoxingdun, China

Noel Celis/Getty

Usually, Luoxingdun (a 10th-century religious island) seems to perfectly float on the surface of Poyang, China’s largest freshwater lake. However, more and more droughts – plus the impact of human intervention on the Yangtze and other rivers – mean the temple's foundations have occasionally been fully exposed in recent years. This image from August 2022 shows the Buddhist temple’s base completely visible for the first time in 71 years.

Luoxingdun, China

STR/Getty Images

The scales of climate change can tip the other way too. This image from July 2020 shows the temple under dangerous floodwaters, threatening its delicate pagoda and ancient Tang Dynasty architecture.

Church of Sant Roma de Sau, Spain

Josep Lago/Getty

The springtime dry spell of March 2023 in northern Spain – one of the worst droughts in half a century – meant that the Catalonia region's Panta de Sau reservoir shrunk to 7% of its usual capacity, slowly revealing the remains of Sant Roma, a remarkably well-preserved 11th-century Romanesque church sunk beneath the lake. It’s the world’s oldest submerged church. In normal times, only the pyramidal steeple can be seen.

Church of Sant Roma de Sau, Spain

Josep Lago/Getty

The church was originally consecrated in 1062, serving a thriving village for centuries through inquisitions and earthquakes, until it was condemned to drown in the 1960s after the Spanish government decided to build a dam on the Ter river. Even the bodies in the church graveyard were exhumed and moved to the replacement town, Vilanova de Sau. During the 2023 drought, locals were able to reconnect with their ancestral village, examining the plethora of unique archaeological features on the church, plus the rubble of old farmhouses.

Seahenge, England, UK

Homer Sykes/Alamy

Growing numbers of fierce storms and rising sea levels are bad news for Britain’s coastline – coastal erosion is increasing at an alarming rate. After a storm hit Norfolk’s shores in 1998 and removed some silt, an amateur archaeologist discovered what he thought was a Bronze Age axehead and an upturned tree stump. It turned out to be a unique circle of 55 wooden pillars and a central altar, constructed in a salt marsh in 2049 BC.

Seahenge, England, UK

Daniel Leal/Getty

‘Seahenge’, as it became known, is thought to have been constructed by the Bronze Age farmers who lived in the area. As with Stonehenge, historians are still not exactly sure why it was built – it could have been used for funerary rituals, or to mark the solstice. In a controversial bid to preserve the henge, the local council opted to remove the wooden pillars from the sea. They are usually on display at Norfolk's Lynn Museum, but in 2022, they were loaned to the British Museum as part of a wider Stonehenge exhibition (pictured).

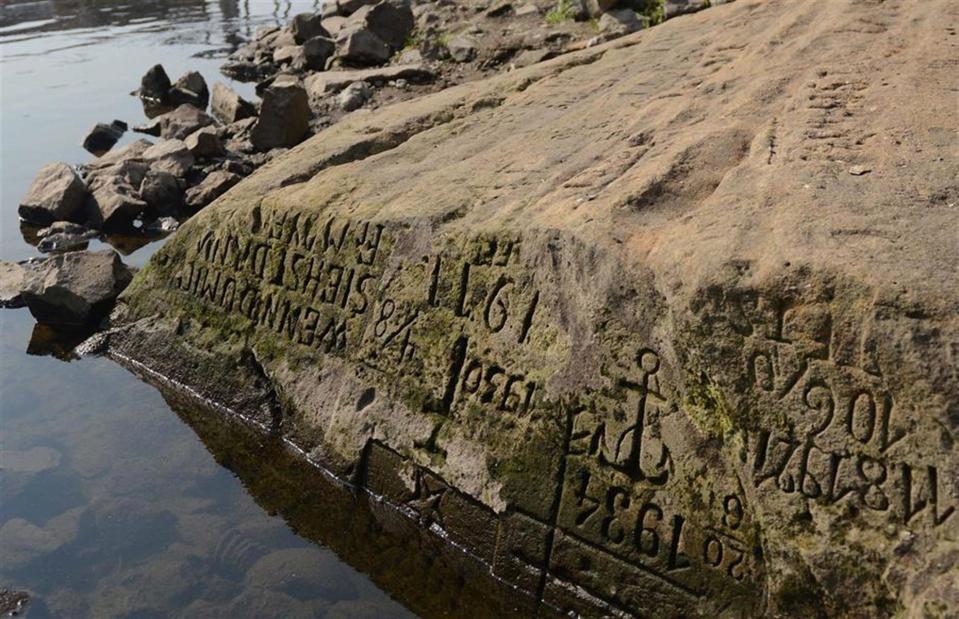

Hunger stones, River Elbe, Czechia/Germany

MICHAL CIZEK/AFP via Getty Images

In the summer of 2022, Europe was hit by record-breaking heatwaves and droughts that killed more than 20,000 people, destroyed crops and saw rivers drop to levels not seen for centuries. The water level fell so low that a series of medieval ‘hunger stones’ were revealed along the riverbed of the River Elbe, including this 15th century stone in Decin in Czechia. Its inscription reads: 'If you see me, then weep.'

Hunger stones, River Elbe, Czechia/Germany

Associated Press/Alamy Stock Photo

These ominous stones bear inscriptions chiselled into them during previous droughts in the Middle Ages. The inscriptions served to mark record low water levels and to warn future generations that if they were seeing them, hard times lay ahead. They had remained hidden under the River Elbe for centuries and were first exposed by the drought of 2018. The more severe drought of 2022 exposed even more hunger stones at various points of the River Elbe between Czechia and Germany.

Now discover the famous world landmarks under threat from climate change