I’ll do it later: my quest to stop procrastinating

At some point, I must do something about my procrastination habit,” is a thought I’ve had at periodic intervals, before deciding to do something else instead. It was last year that I first began to seriously ponder it. January when I mentioned it to my colleagues. A few weeks later when I decided to get advice from some experts. A few weeks more when I set up time to talk to them. And here I am now, in the middle of March, finally sitting down to write about what I learnt from my quest to stop procrastinating.

The piece you are reading has become a running joke among my colleagues. “Oh, by the way, how’s the procrastination feature going, Jessie?” Each time I smile with slightly gritted teeth as I update them on its status. “Not got round to it yet!” But I am far from alone in finding endless things to do in order to put off a task I want to avoid. In 2010, a survey found that 95 per cent of people admit to procrastinating some of the time, while in 2013 a study discovered that 20 per cent of us procrastinate chronically. Writer-director Charlie Kaufman has made high art from procrastination with films such as Synecdoche, New York and Adaptation. In an interview, he said he’d come to realise that, for him, “stalling is a creative technique”. But most of us don’t channel this pesky habit so creatively. In fact, it’s only going to rise because, in our permanently connected, always-on age, distraction and procrastination go together like strawberries and cream (except far less enjoyable). Just this month, more articles have decried the dangers of “bedtime procrastination” – staring helplessly at our phones, and all the other things we do to delay going to bed – inevitably playing havoc with our minds, bodies and souls in the process. Apparently, procrastination is so unavoidable that even pigeons are guilty of it.

The Cambridge Dictionary defines procrastination as “the act of delaying something that must be done, often because it is unpleasant or boring”. I mean, who among us has not sinned? Although I’d class myself as a fairly productive person, my procrastination hits hard when I have to change gears and address a task that requires specific focus and concentration (like, for example, writing a feature about procrastination). It manifests in many ways, including but not limited to: completing every non-urgent work task that I can, checking Slack, making seven cups of tea, checking my emails, doing the washing up, checking Slack again, googling “how to stop procrastinating”, WhatsApping my friends to tell them I’ve just googled “how to stop procrastinating”. Oh, and checking Slack again.

This doesn’t happen every time. But when it does – and even though the work gets done and I don’t miss deadlines – the hours leading up to it are horrible. I hate the immobilising feeling that procrastination gives me – why can’t I just do it? I want to be able to sit down at my desk in perfect harmony, typing away serenely as I achieve effortless productivity and a state of deep, immersive focus! So. I decided that it was time to address this; that it was time for “new year, new me” (three months in now but no worries).

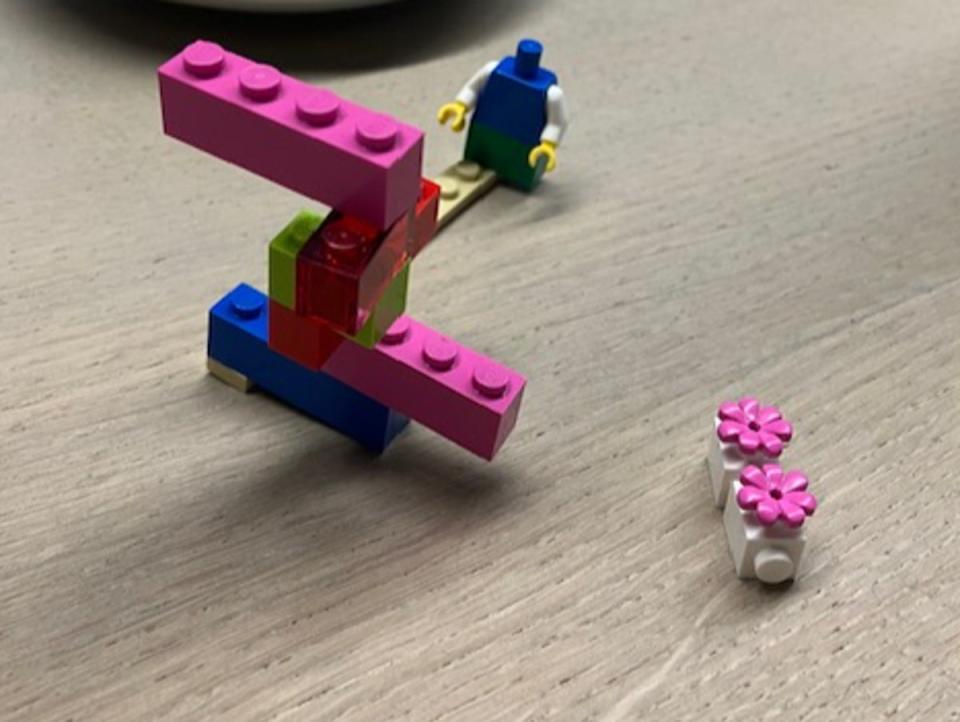

Could I find the perfect hack to eradicate procrastination from my life forever? It turns out it’s not quite that simple. Dr Mahrukh Khwaja, founder of wellness startup Mind Ninja, is a positive psychologist and accredited mindfulness teacher with a zen-like aura of wisdom. She uses science-backed methods around mindfulness and self-compassion to support workplace wellbeing, and when I enlist her help, she starts by giving me some Lego. Khwaja asks me to build something with it that represents my procrastination, and I dive straight in, creating a chaotic pile of different-sized bricks, helmed by a headless person. Essentially: my procrastination is a picture of overwhelm that I don’t feel in control of. As I’m building my masterpiece, she asks me to explain the emotions I feel when I’m procrastinating – frustration, helplessness, anger – and the messages I hear in my head. “I can’t do it,” is generally my main recurring thought.

“Everyone’s on a scale with it, so it’s worth delving into,” she explains. “I’ve heard of procrastinators who will be delivering a talk and literally doing their slides just minutes before they’re about to present something. It doesn’t sound like you’re that level, it’s more that you’re normally quite productive, but you’d love to be ahead of time so you can do other things.” Yes! So why am I putting these annoying obstacles in my own way?

Khwaja shows me something called the “avoidance loop” that seems to capture exactly the trap I fall into. “Psychologists have discovered that procrastination is a result of trying to cope with negative emotions and thoughts, then choosing an unhelpful coping strategy,” she tells me. Basically, it goes like this: unpleasant task creates unpleasant feelings, cue procrastinating with unproductive activities, which triggers a temporary feeling of relief or reward, before the whole thing starts again, going round and round. Procrastination can manifest for many reasons: imposter syndrome, negative thoughts, or as banal a reason as the thing we need to do is just a bit boring.

From our conversation it also becomes clear that something else might be getting in my way: perfectionist tendencies. Done is better than perfect, as they say. But not for a perfectionist, paralysed by the idea that everything they do must be the best thing they’ve ever done. But the negative thoughts that spring from this mindset activate the amygdala part of our brain – its fight or flight alarm centre. This is not good for us, as it triggers the stress hormone cortisol. But the methods that Khwaja teaches, around mindfulness and self-compassion, engage the parasympathetic nervous system, which invites positive emotions. When we think bad thoughts, we actually do feel bad – and vice versa. This is why, Khwaja adds, high performers from CEOs to elite athletes tend to work with psychologists and coaches who help them healthily navigate their perfectionism.

There are specific tools that we can use to counteract what’s going on in our brain, Khwaja explains. There’s mindfulness, which “helps you stay present, rather than getting lost in the story of your thoughts”. She says we should get into the habit of “checking our emotional weather”. For example, what if the day I have a big deadline I’m feeling exhausted, but expecting a level of high performance from myself that doesn’t make allowances for this? There’s self-compassion training, which is about understanding that our struggles are human and we are not alone in them. And there’s also CBT (cognitive behavioural therapy), which is about challenging our negative thoughts.

It’s Khwaja’s advice around perfectionism and self-compassion that gives me a lightbulb moment. “You have an unpleasant task – like writing up an interview or feature. And it’s not unpleasant because of the write-up, because you know how to do that. It’s unpleasant because it’s putting some negative thoughts in your mind, like ‘I can’t do this,’” she explains.

Psychologists have discovered that procrastination is a result of trying to cope with negative emotions and thoughts, then choosing an unhelpful coping strategy

Dr Mahrukh Khwaja

Wait, so maybe my problem isn’t with how I manage my work, but how I feel about my work? And yet, inspired as I am by my conversation with Khwaja, I’m unsure about applying the cuddly sounding principles of wellness and mindfulness to the fast-paced daily life of the newsroom. Jessica Brewer, founder of Emiz HR & Coaching, has a theory that my procrastination might in fact be to do with my profession: journalists are used to working on deadline, so by limiting the time we have to work on a task, procrastination lets us recreate the fuel of that adrenaline rush. But as we talk more, Brewer, an approachable presence who emanates good sense, provides further insight into how my procrastination might be more about my feelings than I’d originally realised. “To understand what’s going to work for you, you really need to get under the skin of what it is that’s going on for you,” she suggests. “What is getting in the way of you doing these things?”

One issue, I mention, is that I struggle to disconnect from the pinging of Slack and my inbox, to feel that it’s OK to be unavailable so I can move into a mode of focused solo work. I’m from a millennial generation that graduated into a jobs market defined by scarcity. As such, me and many of my peers feel an anxiety attached to not responding to everything straight away, lest anyone think we’re not working hard enough. Brewer has practical, straightforward advice: schedule your time, communicate your boundaries, and be disciplined about sticking to both. “Our ways of working have massively changed,” she says. “There’s that fear – you want to always be contactable, because otherwise people will think you’re slacking. That could be something playing into this.”

Scheduling, Brewer explains, can be a useful tool for anything you want to commit to but keep finding ways to avoid. You can book time in your diary for deadlines, but also for gym sessions. Of course, sometimes we need to be flexible – but we should always move these commitments, rather than cancel them. Otherwise we’re back to the same place – it doesn’t get done. And on the subject of things getting done, she adds that there’s a practical logic into how we divide our work into two types: the “important and urgent” tasks, and “important but not urgent”. Because there’s always so much other stuff to do, those “not urgent” tasks get left – until they become urgent. It’s something that is instinctively familiar to me – but is it really procrastination, or just a full plate?

Suddenly, I have a wild theory. What if… procrastination is just part of my process? What I mean by this is that my day-to-day work is intensive, requiring the juggling of a handful of things at a high pace. What if, when I have a deadline, my brain just needs time to reset and reach a new time zone? “There is something about change of speeds, change of what you’re doing, change of focus,” Brewer agrees. “It might well be that what you’re doing isn’t procrastination, it’s having to allow yourself to acclimatise to a different pace, to not being distracted, to being focused. Now, can you get that time down? Potentially, yes.” The next step, she suggests, might be to look at how to “speed up that process of slowing down”.

There’s that fear – you want to always be contactable, because otherwise people will think you’re slacking

Jessica Brewer

Obviously I’m not saying I need to go and walk the Three Peaks in order to be able to meet a deadline, but it makes me feel better to know that maybe what I’m experiencing is more like a workplace type of jetlag. Perhaps I simply need to allow myself time to change rhythms when I have to work in a different way. “One of the things I would look at is the language you use to speak to yourself about it. Are you thinking you’ve got more of a problem than you actually have? How can you reframe that? You’re someone that thrives under pressure – but you’re probably not thinking that, you’re thinking, ‘Oh, I always leave everything to the last minute’.” Again, something happens when my thoughts are reframed. I’m not a useless procrastinator! I’m a busy person who sometimes needs a moment to limber up. Brewer echoes a point that Khwaja has made too: “The negative talk is what’s creating the stress in you, not necessarily the deadline.”

So, it turns out that there is no tool or hack to stop you procrastinating, no secret that will rewire your brain, no magic potion that will make you a fully optimised, constantly productive person. When we do try to work in that way, there’s usually one predictable outcome: burnout. Procrastination, I’ve learnt, is in fact as much about our emotions as it is about time management. But the biggest plot twist of all on my journey to stop procrastinating? I discovered that I’m not actually such a procrastinator after all. A revelation that was worth – eventually – getting round to.

For more information about Mind Ninja visit www.mind-ninja.co.uk and for Emiz HR visit emiz-hr.com