What can we learn from the Janet Jackson Super Bowl documentary?

In January, the New York Times documentary team released Framing Britney Spears, a succinct and bruising retrospective on the pop star’s career and the shadowy legal arrangement that governed her affairs. The 75-minute documentary, which included virtually no new information but offered a cohesive, damning portrait of her treatment by the press, launched a grenade in pop culture. It triggered widespread calls to end her conservatorship, which Spears, 39, later championed (a judge terminated the 13-year arrangement last week); as well as meditations on punishing cultural commentary, callous treatment of mental health, or the hollow, deceptive empowerment proffered by Spears’s sexy teenage image; and a queasy wave of Britney Spears content (including an NYT follow-up, Controlling Britney Spears, that was part retrospective and part, uncomfortably, true crime.

Related: Janet Jackson’s 30 best songs – ranked!

Malfunction: The Dressing Down of Janet Jackson, the latest New York Times documentary for FX on Hulu, aims for the same type of cathartic reframing through an infamous episode of early 2000s pop culture: the baring of Janet Jackson’s breast for nine-sixteenths of a second at the 2004 Super Bowl, and the subsequent cultural firestorm. The 70-minute film follows a similar format to its predecessors – archival footage (including plenty of gag-worthy early 2000s fashion) synthesized with first-person interviews and commentary from cultural critics.

Whereas the Spears films operated as part journalistic investigation into a confusing, shrouded and by all reports predatory legal situation, Malfunction, directed by Jodi Gomes, has a looser objective: resubmit the episode to national consciousness, present the available facts and restore Jackson’s reputation. With participation from NFL and Halftime Show insiders, reporters and critics – though, crucially, not Jackson herself, nor Justin Timberlake, her co-performer who ripped off part of her bodice in the final seconds of the performance – the immediate question is: what did we learn here?

The answer is: not much, at least in terms of new information. Like Framing Britney Spears, Malfunction finds its punch in the power of a simple timeline, a chronological cataloging of Jackson’s trailblazing career (with scant mention of the Jackson family) and the blow-up after the Super Bowl. Handwringing by lawmakers and the disappearance of Jackson from radio, in particular, underscores the absurdity and unfairness of the whole episode, even if there’s not much new to see.

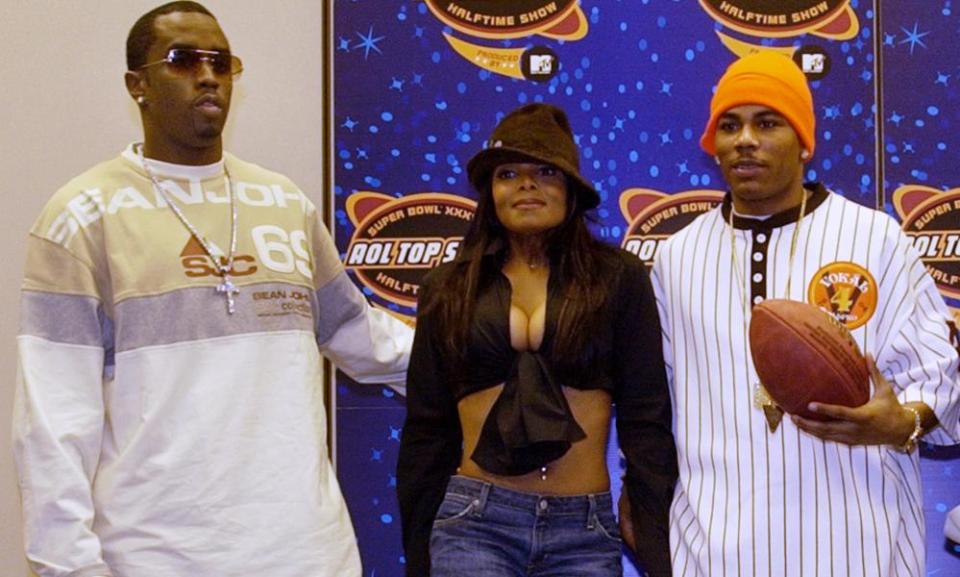

The film-makers did get some access, including the former NFL commissioner Paul Tagliabue and NFL executive Jim Steeg, who reveals that of the halftime show roster that year – Jackson, Diddy, rapper Nelly and Kid Rock (Timberlake was a surprise guest) – NFL brass were least concerned by Jackson.

Salli Frattini, the MTV executive in charge of the halftime show, recalls how said executives, pressed to suggest sex appeal to the broadest swath of Americans possible without becoming overtly explicit, provided a two-page memo of edits to the halftime show days before the event – requested changes to Diddy’s lyrics, Nelly’s lyrics, Kid Rock’s intention to wear an American flag. A plan to have Timberlake tear off Jackson’s skirt to reveal a jumpsuit, timed to his lyrics “have you naked by the end of this song”, was scrapped. Someone on Janet’s wardrobe team visited a tailor, though it’s still unclear what was altered; likewise, Jackson and Timberlake spoke for a few minutes before the show, but it’s not known what was said.

In the aftermath of the show, Jackson was reportedly upset, and unreachable. “Janet fled – we couldn’t get her on the phone, we couldn’t get her manager on the phone,” Frattini says. “She should’ve said, ‘no one knew, and it was a mistake. She never said anything to us. Here we are trying to ask the person that this happened to – because it happened to her – and she was gone.”

Ron Roecker, the former VP of communications and artist relations for the Recording Academy, sets the record straight on Jackson’s absence from the Grammys, which CBS aired a week later. The then CBS chief, Les Moonves, he says, decided that both artists had to apologize on the air, on top of their written apologies, to attend the show. Timberlake agreed (and said on-air “I know it’s been a rough week on everybody [to laughs], what occurred was unintentional, completely regrettable, and I apologize if you guys are offended”); Jackson did not attend.

Related: Stage fright: the tricky unease of the Britney Spears documentaries

“It felt like another request for something that was an accident,” says Matt Serletic, former CEO of Virgin Records, Jackson’s record label at the time. “Something that didn’t need to be laid completely on her. And so she didn’t do it, and good for her.”

If there is a singular villain in the story, it’s not Timberlake, who comes across as a career-hungry star more willing to kiss the ring and more culturally suited to escape the fallout. It’s Moonves, toppled after numerous allegations of sexual assault and harassment in 2018, who was reportedly incensed by the episode and demanded an in-person apology from Jackson and Timberlake (Timberlake reportedly agreed).

Malfunction is less a revelatory film than a swift recounting of an episode many already remember, one whose obvious corrective mandates have, by and large, passed. Timberlake was invited back to preform the halftime show in 2018, to much criticism; earlier this year, in the wake of Framing Britney Spears and the mainstreaming of the #FreeBritney movement, he issued a personal apology (in an Instagram statement) to both women. Jackson is widely considered a trailblazer in popular music, and the film ends with Jackson’s induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2019. (There’s also a final note revealing that she and Timberlake still share the same publicist, which I have questions about!)

“Our culture doesn’t know what to do with independent women, and definitely independent Black women,” says the New York Times critic Jenna Wortham in the film. “And forget about an independent Black woman who makes her own money, who knows who she is and is apparently a completely sexually liberated woman. When there was an opportunity to punish her for it, they did.”

But Jackson may still have the last laugh, or at least the opportunity to delve into or completely ignore her lowest public episode at her choosing: her own first-person documentary, Janet, will air in January on Lifetime and A&E. It will perhaps offer another chapter to this era’s many revisions of 2000s pop culture history – or just a chance to hear the voice that’s noticeably missing here.