Black dads are more likely to play, dress and share a meal with their child, data shows

Editor’s note: Get inspired by a weekly roundup on living well, made simple. Sign up for CNN’s Life, But Better newsletter for information and tools designed to improve your well-being.

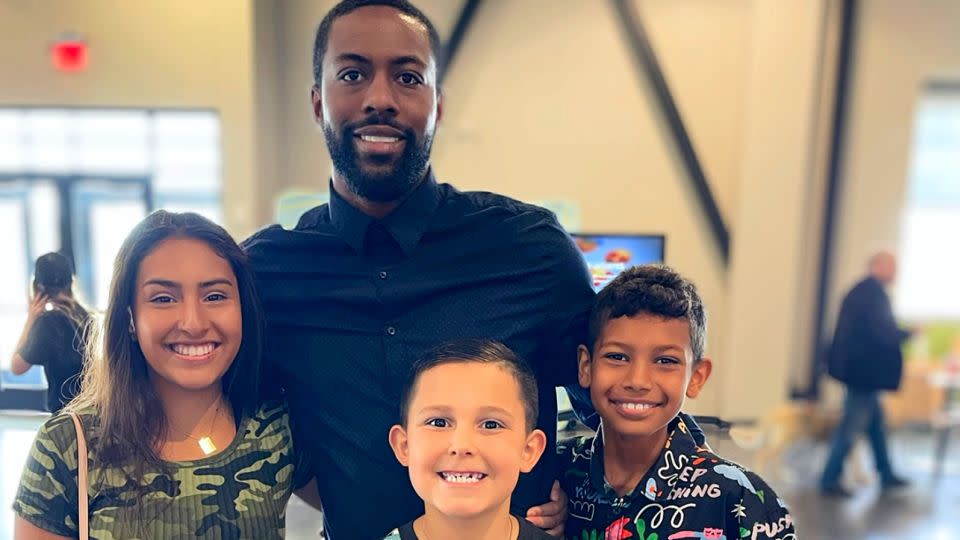

As he was growing up, Jeremy Givens says the narrative he heard around Black fathers was different than the one he lived.

In movies, television and generalized conversation, they were portrayed as absent, not engaged and overall, not very good fathers, he said.

“In my own experiences — not just with my father but with my uncles and my colleagues and my grandfathers — it was something that was polar opposite, something that was wonderful, that was inspiring, that was nourishing,” Givens said.

Now a father himself, Givens is president and executive director of the Black American Dad Foundation, an organization aiming to counter biased perceptions of Black fathers with firsthand accounts.

Fathers and mental health experts told CNN they are sharing the importance of fatherhood and their experience with and as Black dads.

Fathers are important for helping their children see all they can be, said Dr. Jennifer Noble, a licensed psychologist based in Los Angeles.

Seeing both moms and dads changing a diaper, nurturing a child and engaging in play helps boys and girls relate to both of their parents, she said.

“Therefore, as a kid, I get to identify both versions of it, and figure out what fits best for me,” Noble said.

What we know about dads

A classic image of the traditional father figure shows him with outstretched arms trying to coax a fearful child on the edge of a pool into the water.

“The father is in the pool and says, ‘OK, jump, jump, jump into the pool!’ And the kid is scared,” Noble said. “What they’re doing is trusting, but then they’re accessing bravery … to jump into the water because they know father’s there to take care of them.”

Often, good fathers can offer lessons in playfulness, care, support, courage and discipline, Noble said. And data shows that Black dads are doing so regularly.

Seventy percent of Black fathers who live with their children were most likely to have bathed, dressed, changed or helped their child with the toilet every day, compared with their White (60%) or Hispanic (45%) counterparts, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2013 National Health Statistics Report.

Those Black fathers were also most likely to have eaten a meal with their children, the data showed.

These numbers were high, and not just for biological fathers living inside the home, said Dr. Erlanger Turner, a licensed psychologist and associate professor of psychology at Pepperdine University in Malibu, California, via email.

“It also indicates that Black fathers often step into the role of (stepparent) or maintain consistent involvement when living outside of the home,” he added.

This involvement is important for many reasons, one of which is that data shows that children with involved fathers are at lower risk for developing disruptive behavior and mental health difficulties, Turner said.

Even when a biological father isn’t present, the role can be filled by other men who care about the child — an important concept in African American culture, Noble said.

“You can have perhaps multiple fathers or father figures and grandparents, who can play a very strong role that is just as strong, if not stronger than the father,” she said. “You really do have uncles and grandparents and coaches and community members, pastors that can step in and really provide all those things like the guidance, the empathy, the attunement and support.”

How media portrayals get it wrong

If data shows that Black fathers are often involved in the daily care of their children, why is that story not being told?

Often, movies, TV shows and news stories about Black fathers come from secondary sources — not by Black dads or those who have been raised by them, Givens said.

As a result, the father of a Black family can be portrayed as either absent or not a very good dad.

“Sometimes we miss some of the nuance and just think, ‘Oh, that’s every Black family everywhere,’” Noble said.

Given the history of racism in the United States, some Black fathers may face disproportionate incarceration rates or have difficulty in obtaining jobs to provide for their families, she added. But such hardships are only part of the story of Black fatherhood.

“Maybe we need to change the evidence that’s available to really kind of get a more representative picture,” Noble said.

How to right this narrative

For a narrative that better represents Black fathers, we need to emphasize who is telling the story, Givens said.

The Black American Dad Foundation and other groups are trying to put out stories from Black fathers themselves, Givens said. He wants more primary sources for the cultural understanding of Black families.

He also encourages dads to think about the behavior they are modeling for their children.

“I think it’s important to show your children that you are human and that you make mistakes and it’s OK that you find ways to get through them,” Givens said. “Not only do you show them your successes but show them your failures as well.”

And fathers shouldn’t be afraid to show their vulnerable side to their children, Turner said.

“For boys, it really is helpful to have male figures model healthy coping and emotional expression,” he said. “While mothers can also play an important role, I think it lands differently when boys see how their father is able to confidently talk about emotions like sadness or anxiety.”

Yet doing so isn’t always easy. Givens recalls his own difficulty a few years ago when he told his son, Cohen, that he was moving out of state and wouldn’t see him for a few weeks.

“This doesn’t change anything,” the single dad remembers saying to his son, then 5, who now lives in Arizona with his mom. “I want to make sure you know that I love you, and I will always love you and be with you.”

Givens can’t forget his son’s response. “It’s OK, Daddy. You just have to try,” he recalled the boy saying.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com